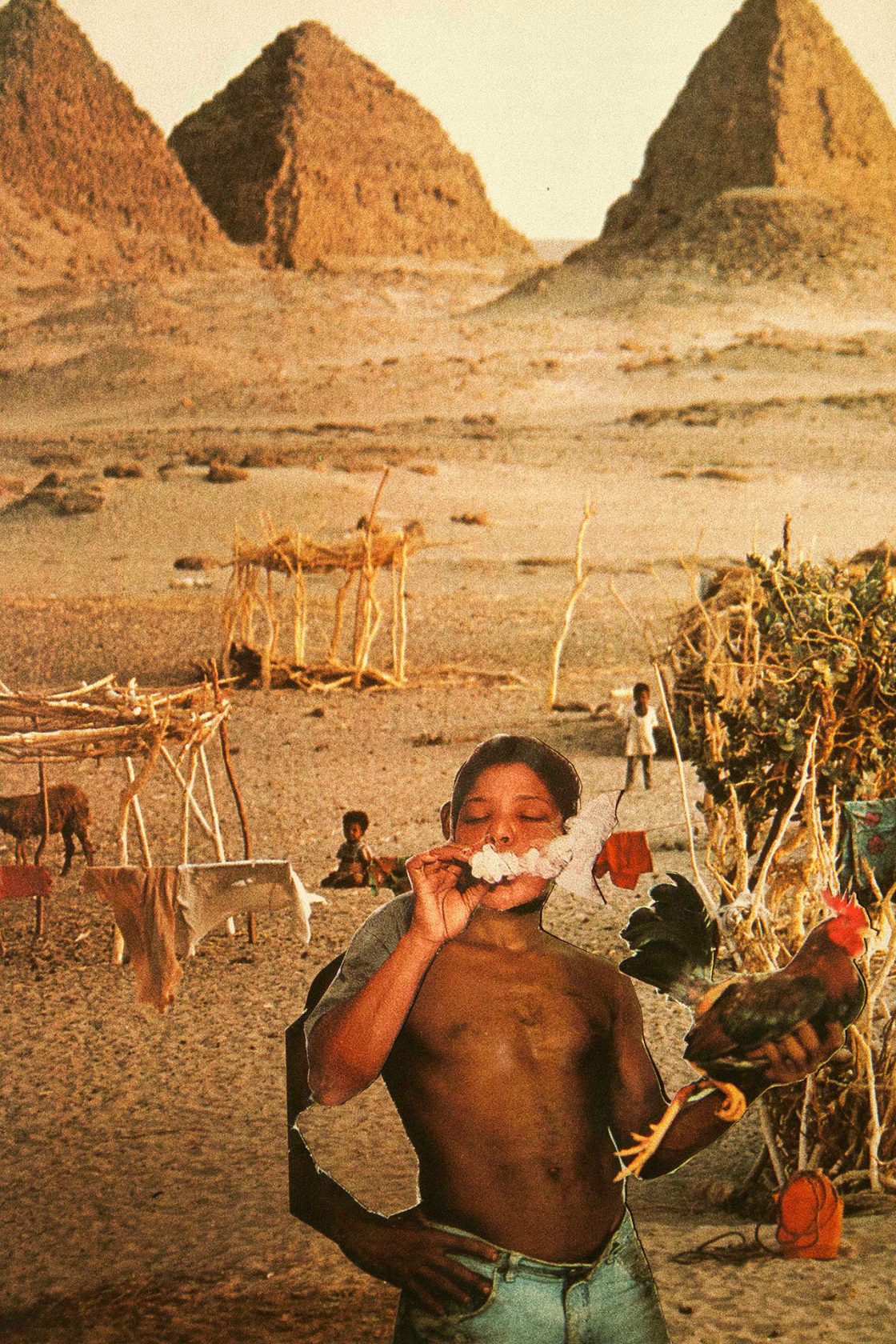

#90 The Belly is Strange

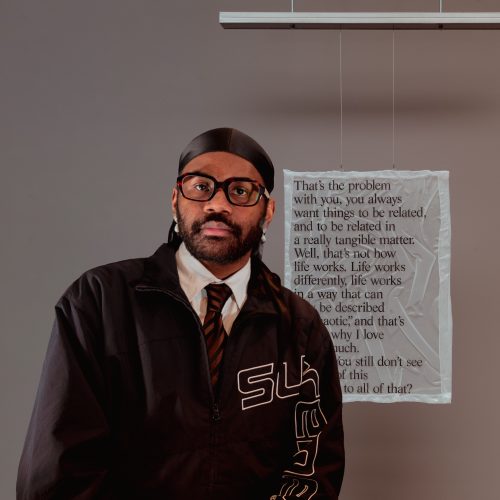

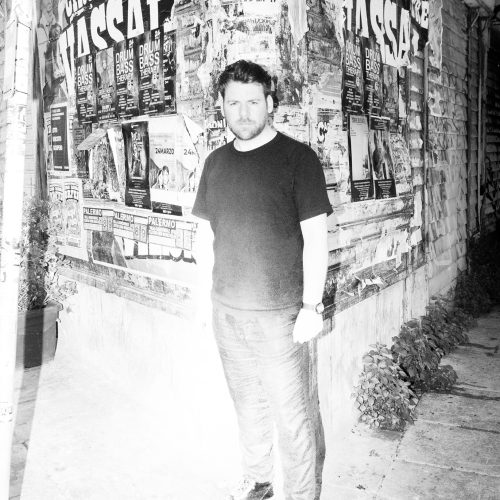

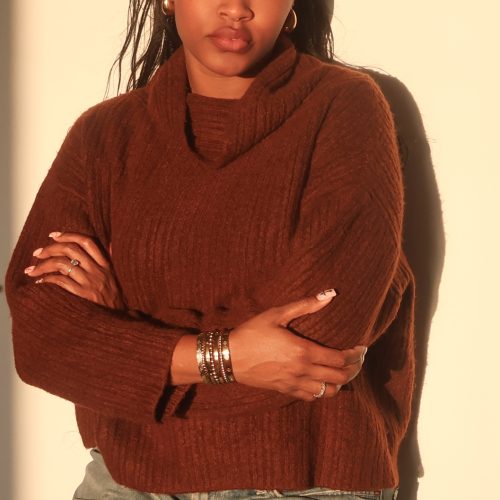

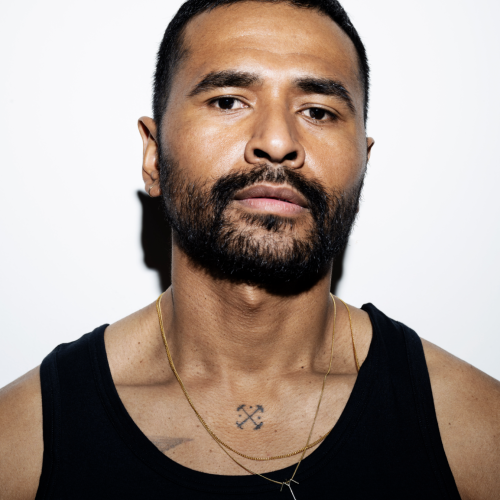

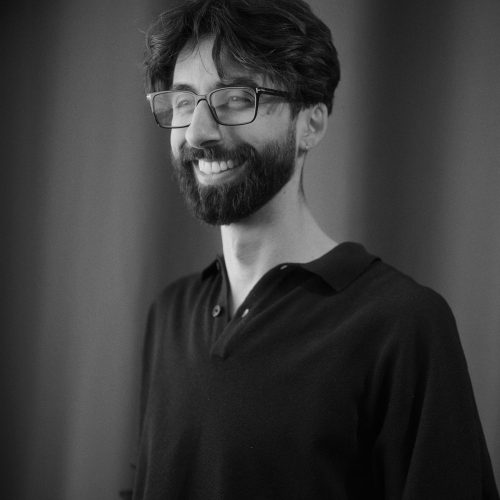

A reflection on 'The Belly of Momo' written by glenpherd, informed by Rita, Kevin and Lakisha

aya

na Watamula

we shared a belly

no ku lombrishi

ma ku un rosea

i un lus

pero ya Momo a bolbe

for di shinishi

e ta yamando

bin kas

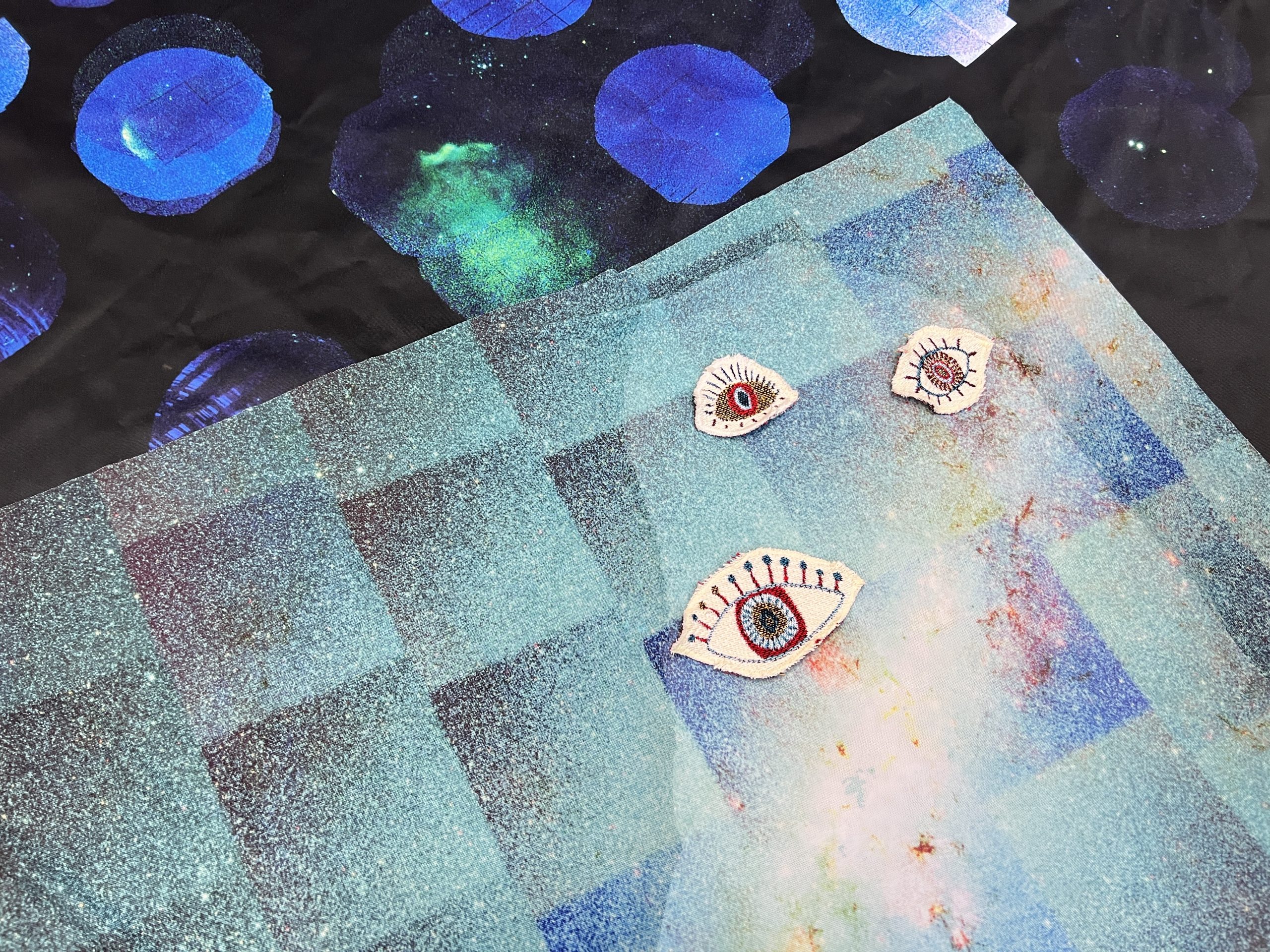

enter the belly

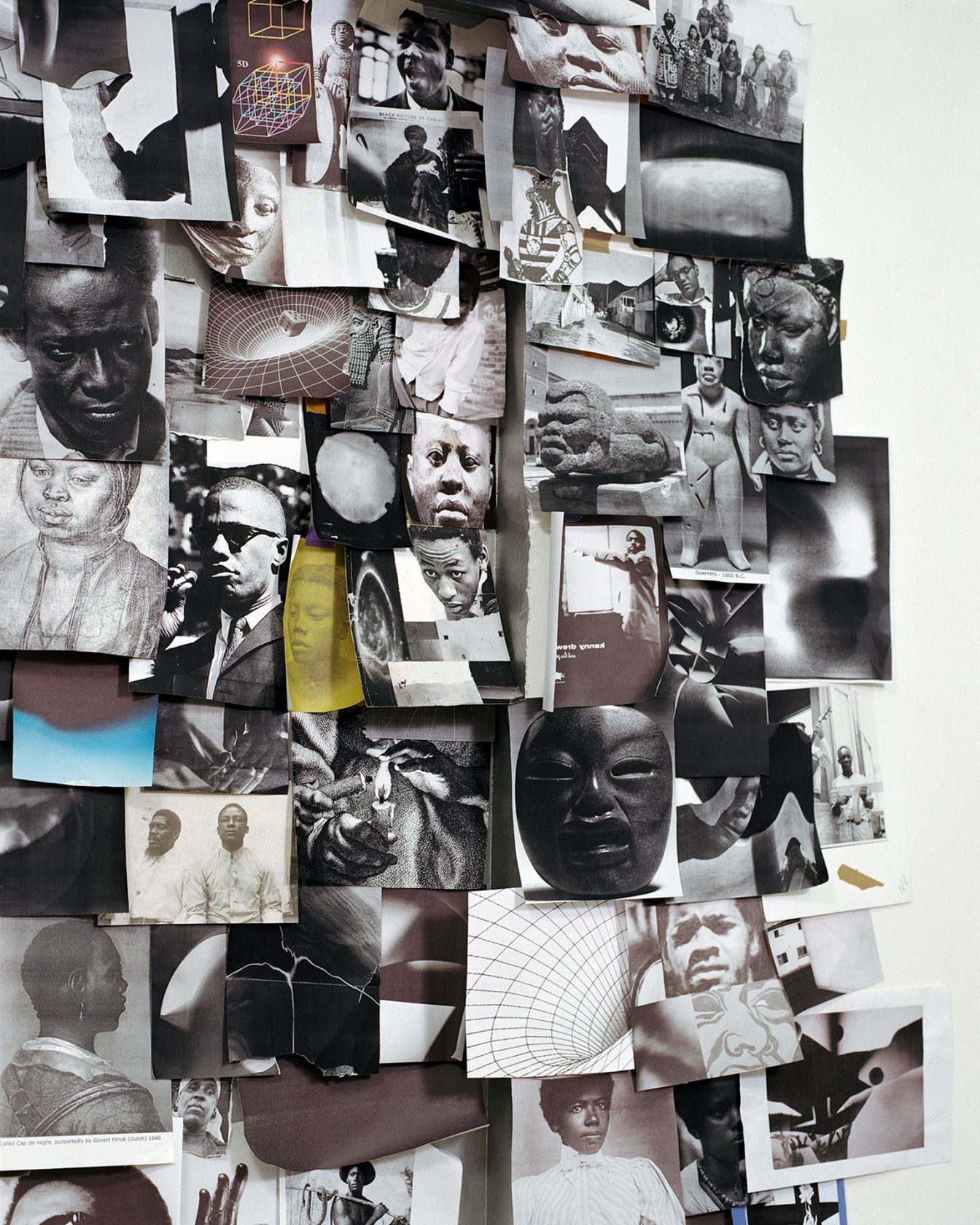

When The Belly of Momo invites us to “enter the belly,” one might at first glance easily misconstrue it as a geographical location. However, ‘the belly’ as I understand it denotes a myriad of things at once. As Stuart Hall, a Jamaican-born cultural theorist, points out in his (auto)biography Familiar Stranger, there is a broader ontological dependence that manifests in distinctly Caribbean “conditions of existence”¹. This mode of being—a distinct Caribbeanness—refers to a state “into which [Caribbean people] had been inserted and called into place by birth and by [their] early formation,” consequently relegating them to live “on the hinge between colonial and post-colonial worlds … without ever being fully of either.”² The sensibility for such antonymic and contradictory connections is necessarily predicated on particular lived experiences, and invariably has implications for the way that we conceptually attend to the fragmented histories, geographies, identities, cultures, and epistemes of the Caribbean.

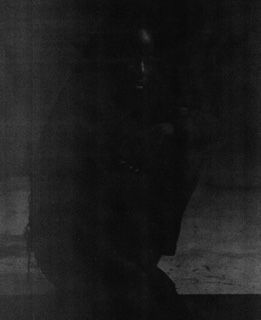

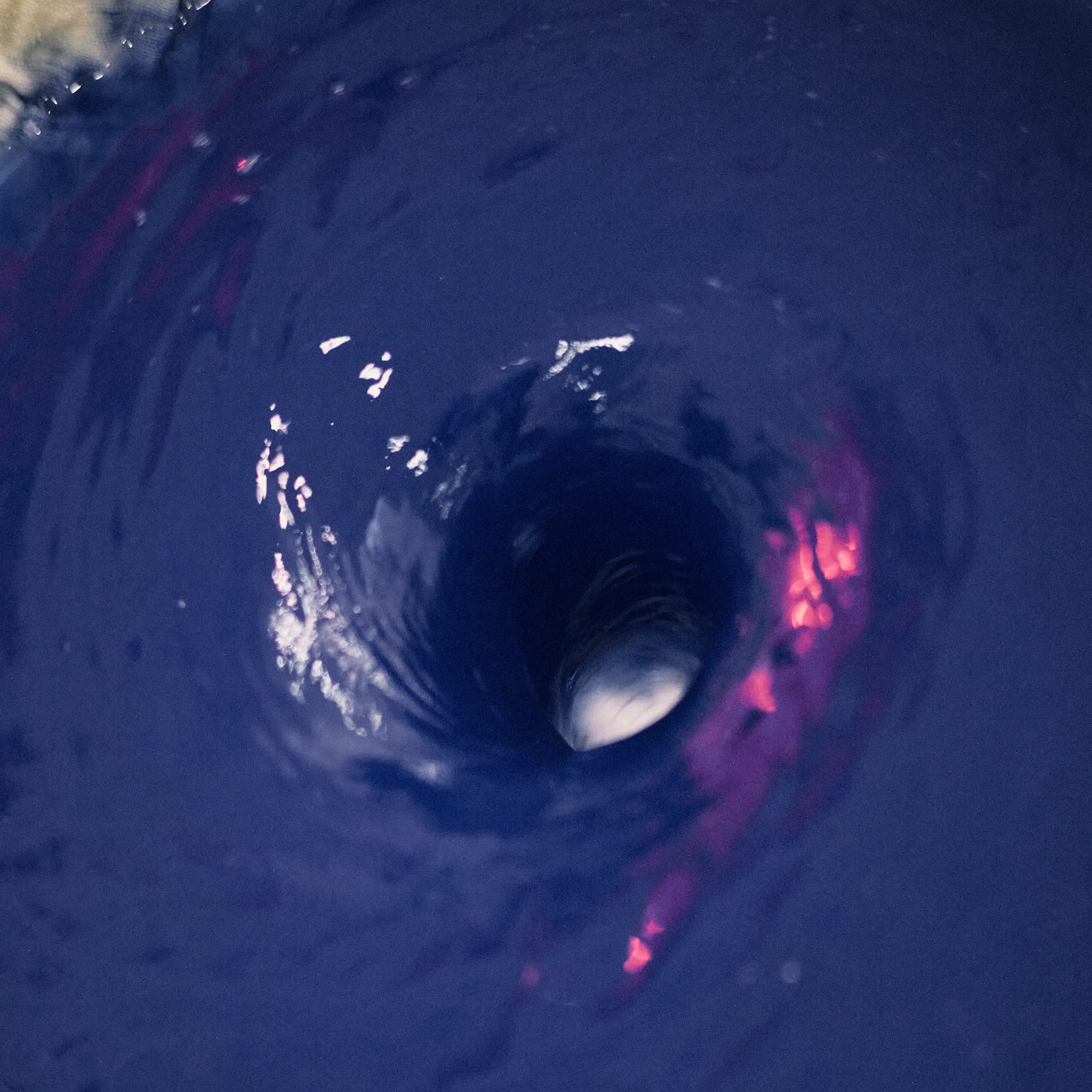

It is here that the belly emerges for me—not as a fixed space—but as a phenomenological situation. The belly is not place; it is condition. A praxis of carrying, metabolising, and transmitting what exceeds representation. And yet, because it is so deeply tied to lived experience, it continues to move with a rhythm that is unmistakably Caribbean in its complexity: recurrence, contradiction, and persistence. To inhabit this belly is to inhabit a history that pulses under the skin, to feel the echo of events one has not personally lived but which remain insistently present as vibration. The temporality of this condition is recursive, spiralling, returning us again and again to our past. In this sense, the belly gathers what official histories often exclude: the sensory, the affective, the opaque, the intimate. It makes legible the modes of knowing that do not fit neatly into the frameworks of Western epistemology.

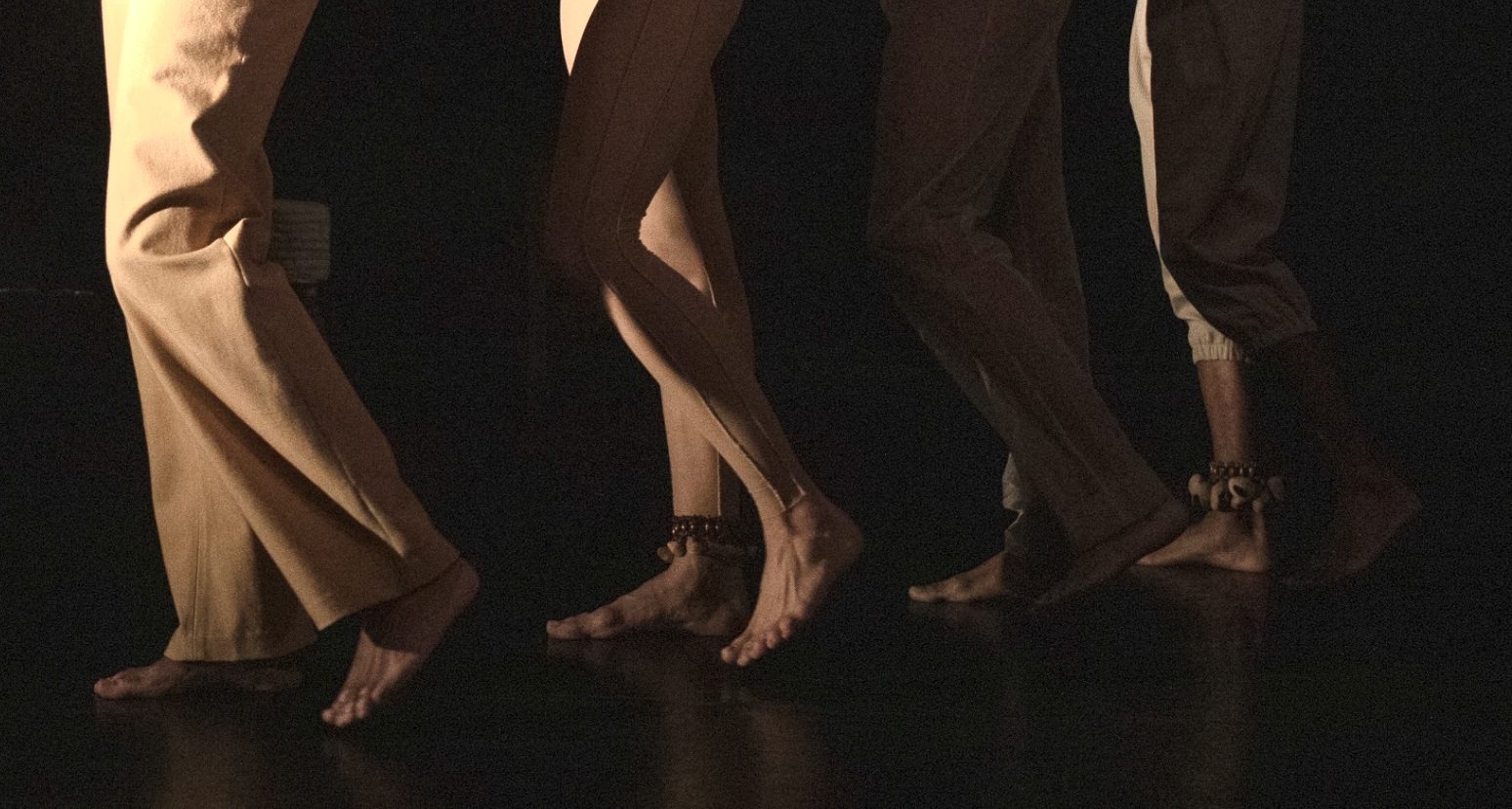

This orientation becomes clearer when we consider the way memory circulates in certain oral and embodied traditions of the Afro-Caribbean diaspora. Memory does not only record (in the mind); it imprints, touches the nervous system, shaping posture, voice, breath. It forms part of the conditioning that configures how one learns to perceive the world. Rather than an archive one consults, such memory forms an archive one must carry in the body. And carrying it—to borrow from Wigbertson Julian Isenia—is often straño. Strange in the sense of feeling something that is both intimately yours and yet older, heavier, and more expansive than the boundaries of a single self.

In this respect, the sensory modalities (visual, sonic, tactile) become philosophical operators rather than aesthetic embellishments. They articulate what cannot be straightforwardly spoken. They give form to the residues of history that surface as sensation. A tremor in the chest. A periodic tightening of the jaw. The feeling of walking with someone else’s steps. These are methodologies for surviving and interpreting a world in which the past remains structurally unresolved.

The belly is thus generative. It produces subjects who are always negotiating an inheritance that speaks through them even when they fall silent. This is complex ontological condition in which one is asked to be historian, witness, and bearer simultaneously—even when the memories in question do not originate within one’s own lifetime. After all, besides simply remembering, there is also the task of transmission.

This raises a question that sits at the centre of the belly: how does one honour inherited memory without being consumed by it? Caribbean subjects have long been asked to perform a balancing act between acknowledging historical violence and forging new possibilities that do not reproduce its logic. Hall’s articulation of the hinge between colonial and post-colonial worlds describes this tension succinctly: to belong to neither fully means that one is tasked with inventing modes of being that need not resolve contradiction in order to remain coherent. In the belly, contradiction is structure rather than failure or destabilisation.

The Caribbean condition does not always require synthesis but requires coexistence. A recognition that paradox is generative, that the dissonances we inherit can serve as points of orientation. This is where the philosophical value of the sensory returns: in the belly, knowledge is tactile before it is conceptual. One learns to navigate by feeling, by listening, by sensing the contours of what refuses articulation. This is not mysticism but it is methodology; one honed over generations in communities whose histories have been systematically obscured or fragmented.

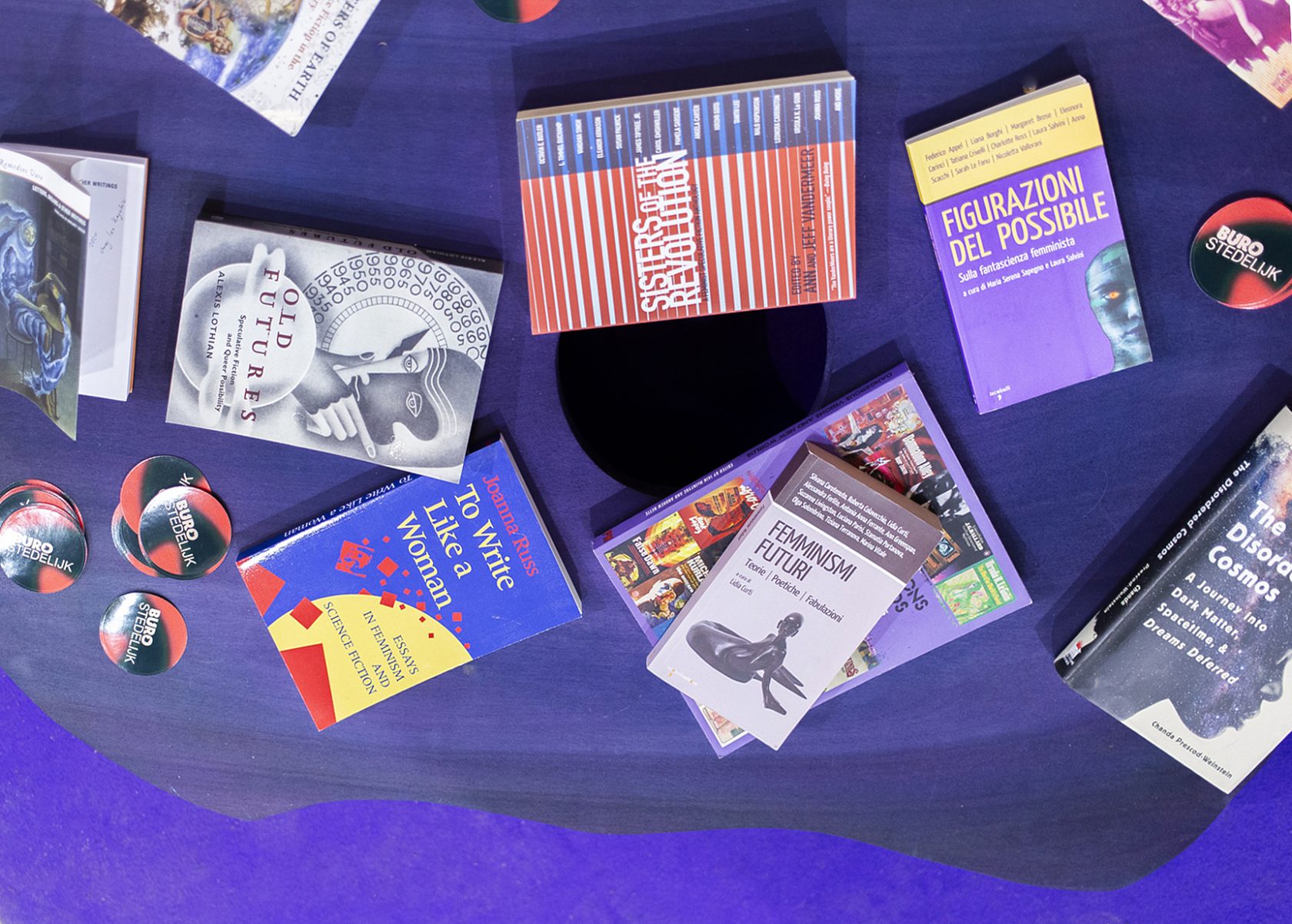

The work, then, is to remain attentive to these subtler forms of knowledge without attempting to translate them into something more palatable to dominant epistemological frameworks. This attentiveness involves accepting opacity. Accepting that not every resonance has a name. Accepting that some memories travel as rhythm rather than narrative. To inhabit the belly is to relinquish the desire for full clarity and instead cultivate a practice of recognition: recognising echoes, recognising absences, recognising the way certain sensations return without clear origin.

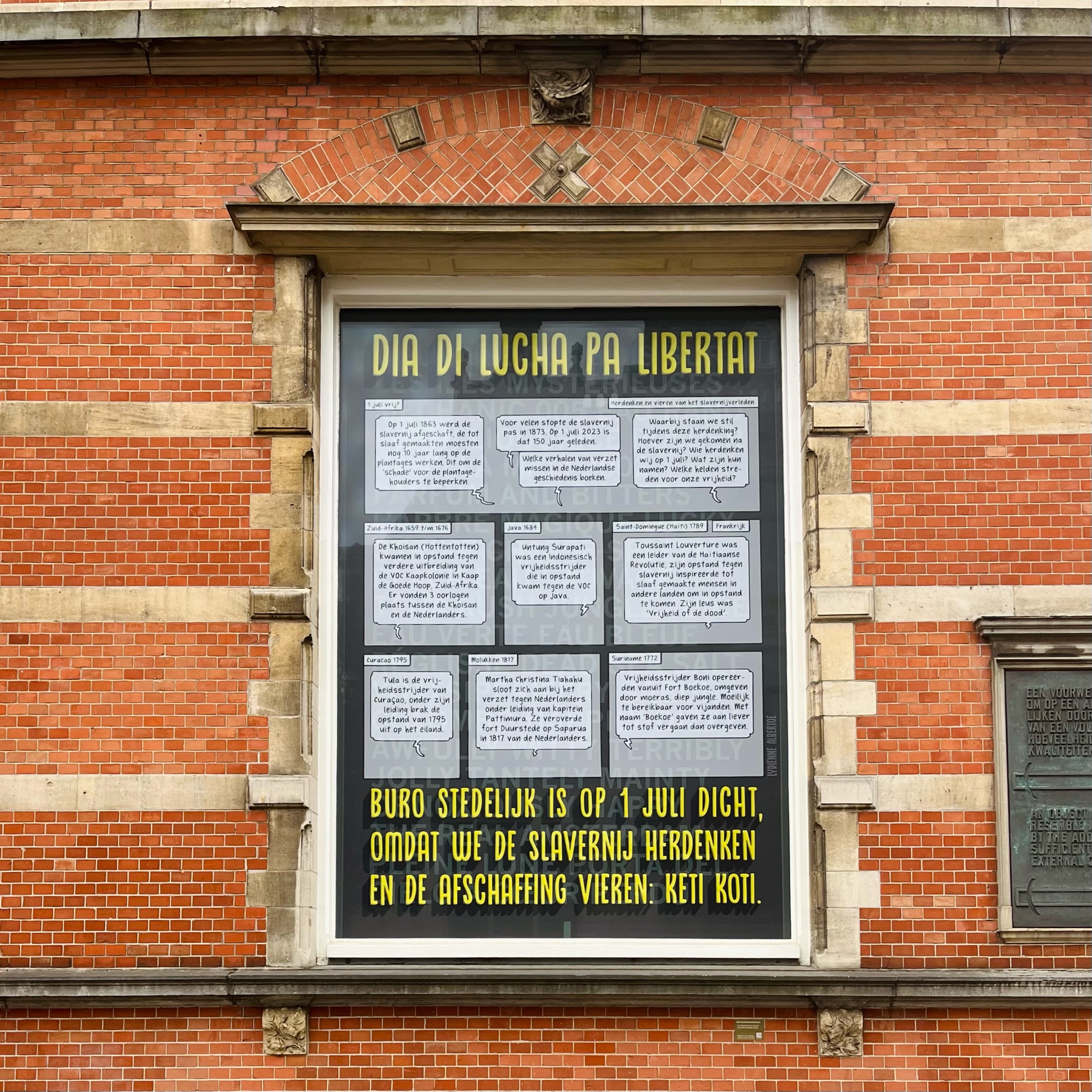

There is also, within this silence and resonance, a politics. Not a politics of aesthetic spectacle but of relationality. To affirm the belly as a site of knowledge is to affirm the legitimacy of those forms of history and perception that have been dismissed as illegible or irrational within colonial epistemologies. It is to claim space for a mode of being that is grounded in its own internal logics. The belly insists that Caribbean being is defined by an overflow of possibility.

This possibility complicates the question of futurity. If the belly is a reservoir of recursive temporality, then the future cannot be conceived as a break from the past. Instead, it emerges as reconfiguration, as repetition-with-modification. The future then grows through history rather than away from it—much like the way sensation can transform over time without losing its original contour. The structures shaping Caribbean identity do not fully disappear; they shift and mutate. Our task is to develop new modes of inhabiting these structures.

Here again, straño is essential. The strangeness of feeling oneself shaped by forces one cannot fully articulate becomes a compass. It guides without offering direction. It gestures toward a future that honours the past without becoming beholden to it. In this way, the belly becomes a space where contradiction, opacity, and sensation form the groundwork of possibility.

Ultimately, the belly offers a way of thinking about Caribbean identity that moves beyond essentialism and representation. It accounts for the lived complexities of navigating inherited memory, ongoing structural conditions, and the sensory dimension of being. It affirms that our histories are internal, shaping our gestures, our silences, our modes of relating. And in affirming this, it offers a way of resisting the flattening impulses of dominant narratives.

To enter the belly, then, is to step into a mode of existence that recognises relation over isolation, resonance over chronology, sensation over certainty. It is to acknowledge the depth of the past without allowing it to foreclose the future. It is to move with the understanding that what we carry is not solely ours, and yet it speaks through us in ways only we can interpret.

It is straño, yes—but it is also home.