#89 We Need to Relearn How to Walk Softly on Earth: Questioning while Co-Becoming, from Curating to Publishing

Reflections on making 'How We Made Noise' by Gwen Parry

King Francis I of France was a prodigious patron of the arts, drawing artists such as Leonardo da Vinci to his court—Da Vinci, notably, bringing with him the Mona Lisa. Born in 1494, Francis I’s reign marked the beginning of French exploration of the so-called “New World,” laying foundations for the first French colonial empire. He was also known to carry with him a pouch of powdered human mummy mixed with rhubarb: a quick remedy for injury, a curative he trusted. The use of ‘mummy powder’—believed to be a panacea capable of healing a wide spectrum of ailments—was widespread in Europe between the 12th and 17th centuries. Extracted, traded, and ingested, it literally fed a colonial corpus seeking to soothe itself with the remnants of others.

Fast forward several centuries to the present, when art patrons and institutions are seeking not cures for their own bodies but strategies for tending to the historical harms embedded in their foundations. Over the past decade, at a larger scale than ever, museums have attempted to treat inherited ailments—of collections, policies, habits, hierarchies—through new hires, revised acquisition strategies, and shifts in institutional tone. Much has been written about the burden and sacrifice expected of those brought in to enact such change, often within buildings shaped by the very histories they are asked to redress—wondering why the salvation we hunger for has left many feeling devoured.

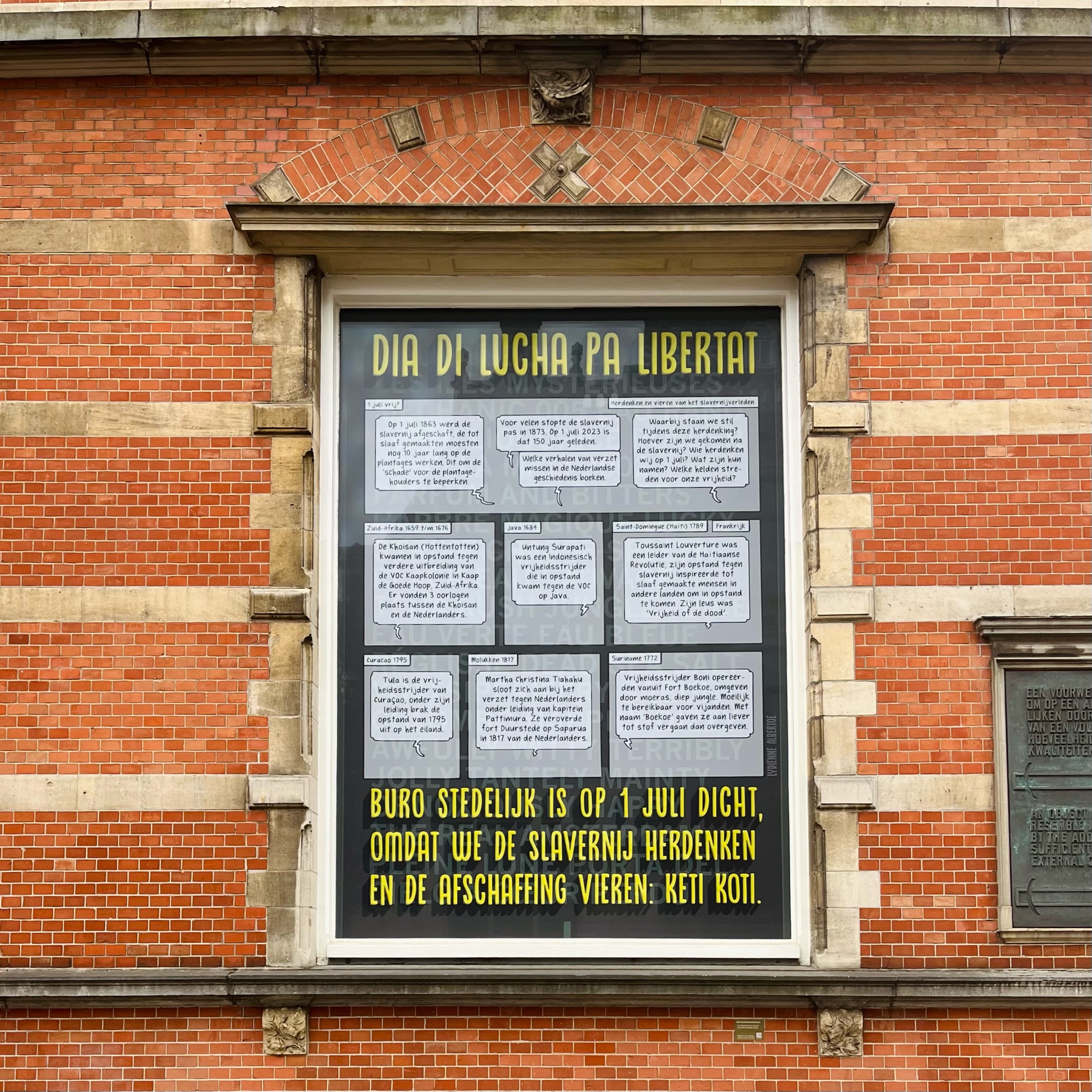

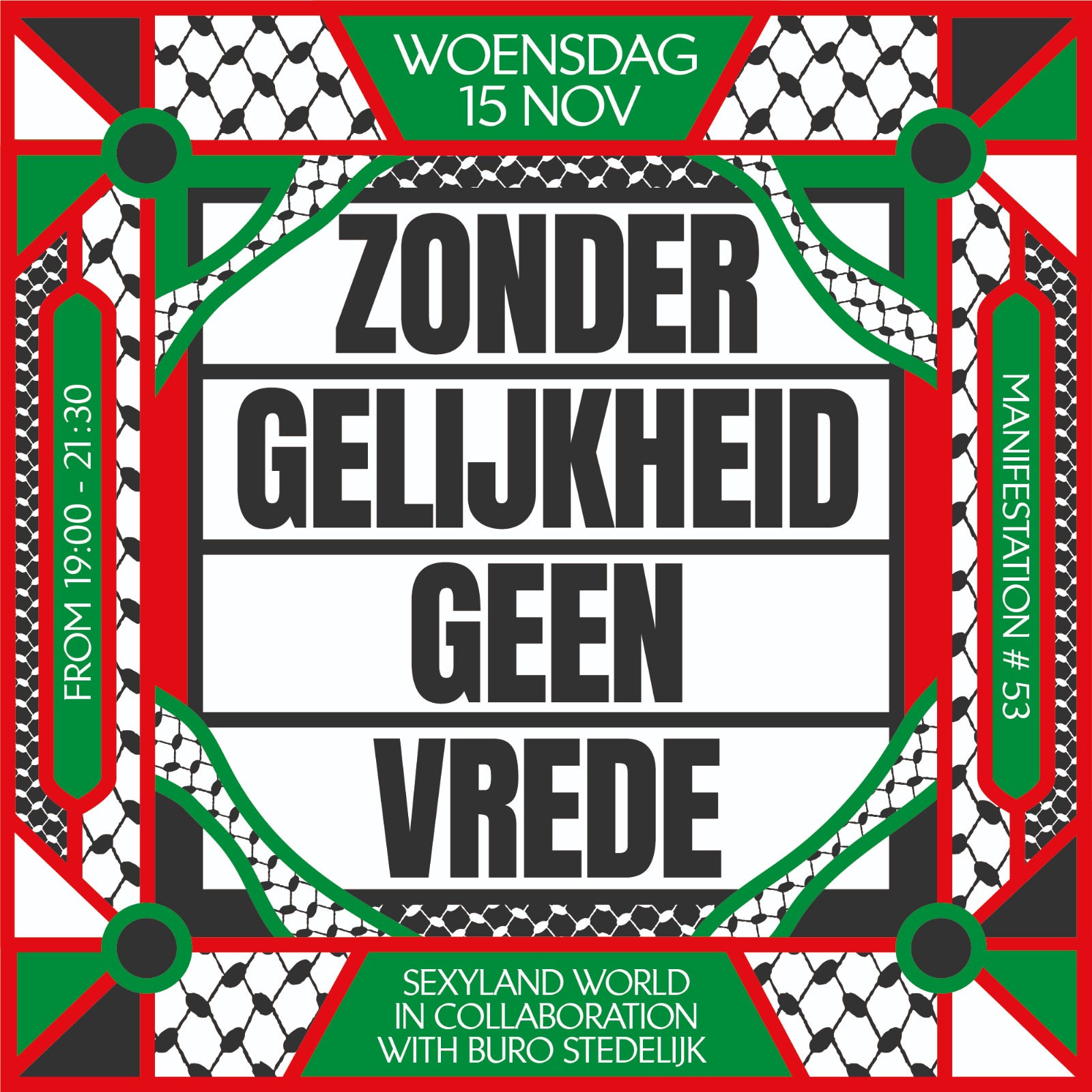

As a project space inside a museum, Buro Stedelijk offers a compelling example of such germination, of a museum seeking to welcome a change of sorts. Charged with teasing out new possibilities by taking up literal space, carving out programmatic autonomy, and sustaining an independent curatorial rhythm across three years, Buro sought both to deviate gently from its host and to rub up against it—sometimes abrasively, sometimes tenderly.

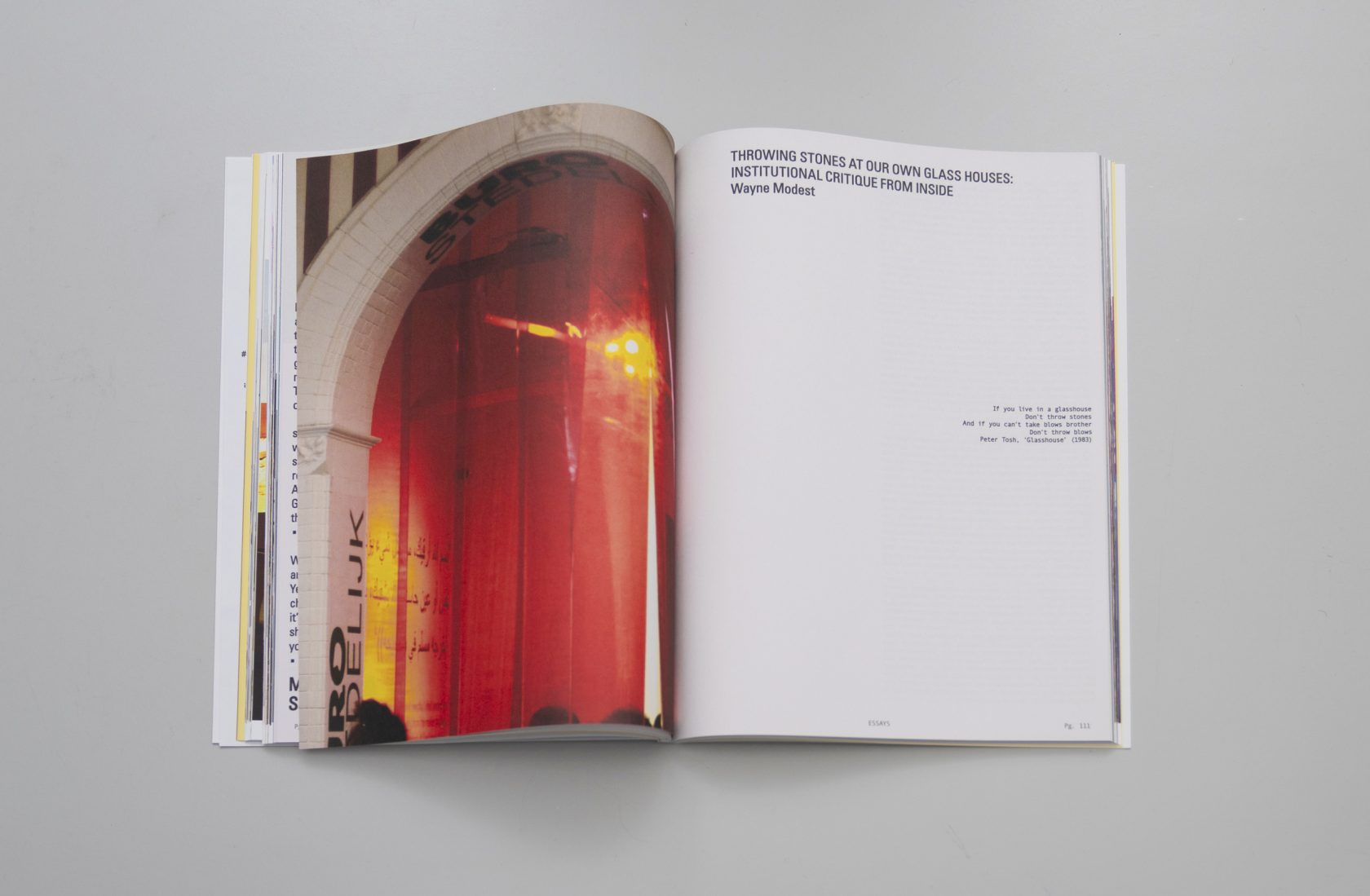

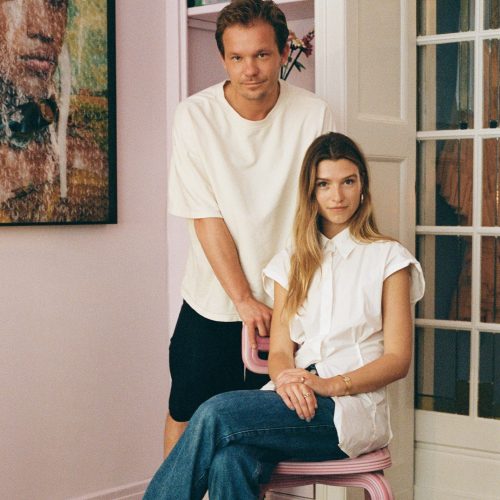

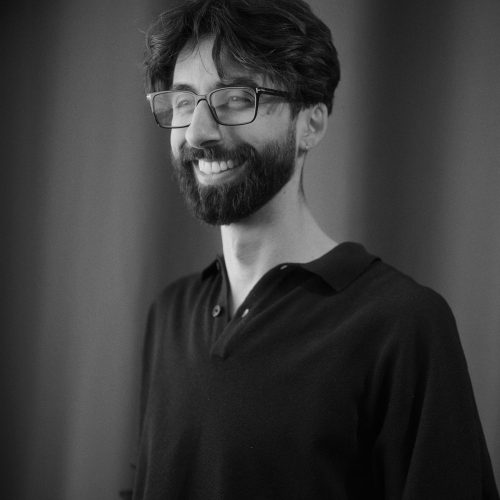

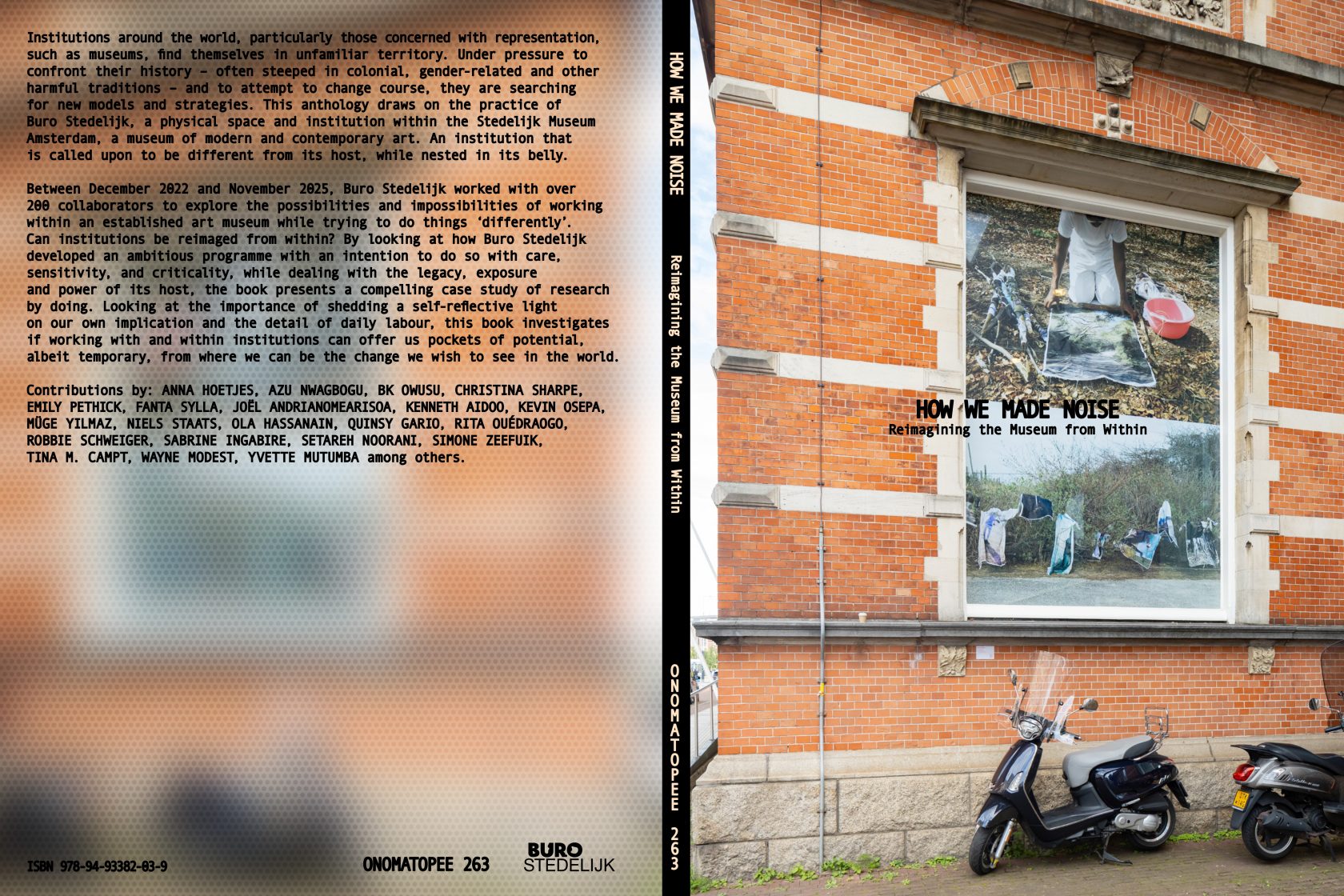

To document this unfolding, co-founding curator Rita Ouédraogo and project manager Niels Staats invited me early on to imagine a publication alongside them. If art is not a mirror held up to reality but a hammer with which to shape it—as Bertolt Brecht once suggested—then what metaphor suits a book that chronicles the slow, deliberate resculpting Buro set in motion? We conceived of the publication not as a reflection of the activism embedded in the program, but as a whittling instrument in its own right, committed to the transformative, curatorial nature of storytelling. How we narrate the work is how it will be archived, the intention for how we want it to be captured. This project grew into How We Made Noise: Reimagining the Museum from Within, completed at the end of Buro’s first term in November 2025.

As a book about an art space or program, this one was to become something different, as one of the stories that nudged itself to be told is that of Ouédraogo and Staats as fully aware of the experimental nature of their assignment. They approached the space much like artistic and design researchers: by simultaneously doing, questioning, reimagining, and iterating. Their practice was akin to that of participatory action researchers—an approach that centres experiential knowledge in addressing problems produced by harmful social systems, and in envisioning alternatives while at the same time trying to work them into being. In Buro’s case, this meant a persistent interplay of experimentation, reflection, and structural intervention.

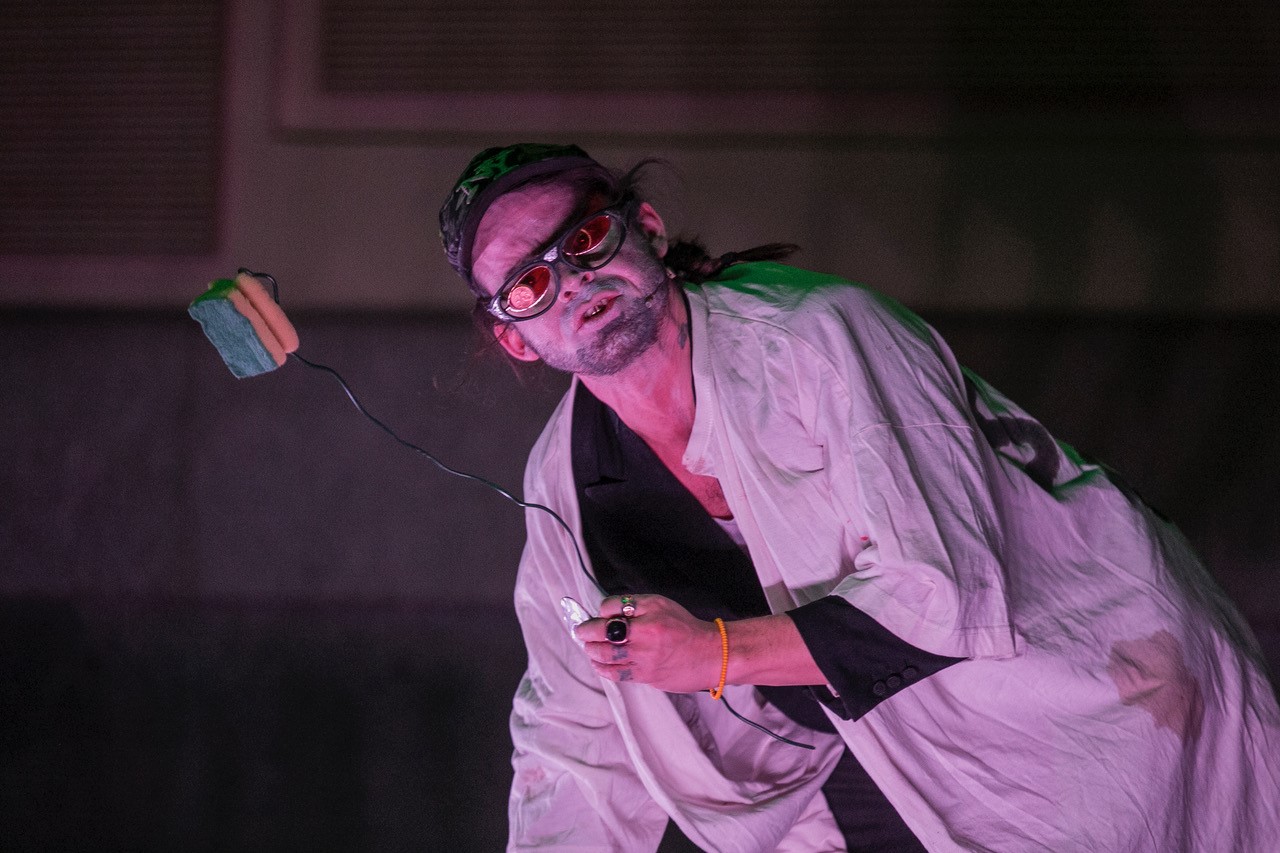

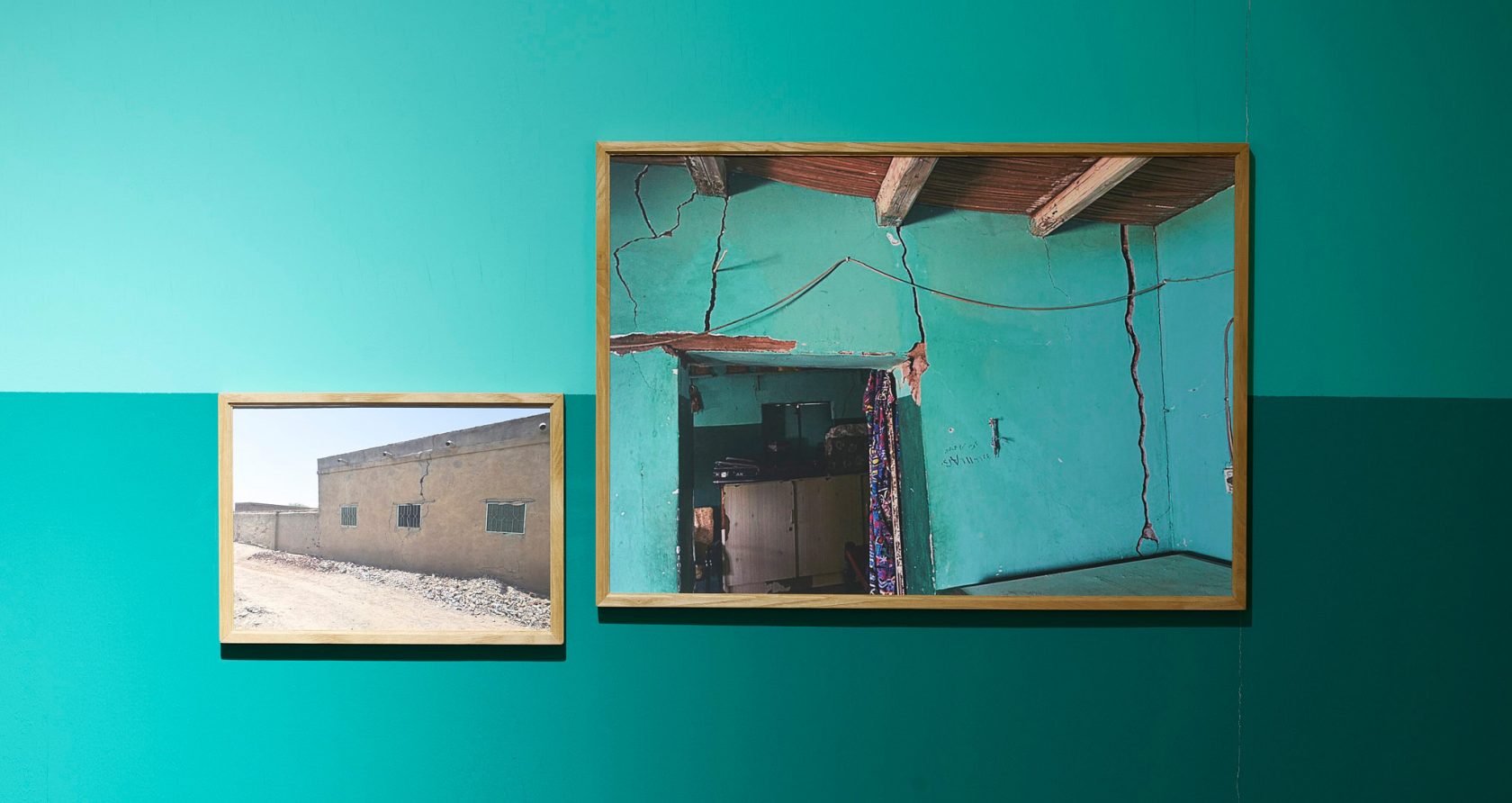

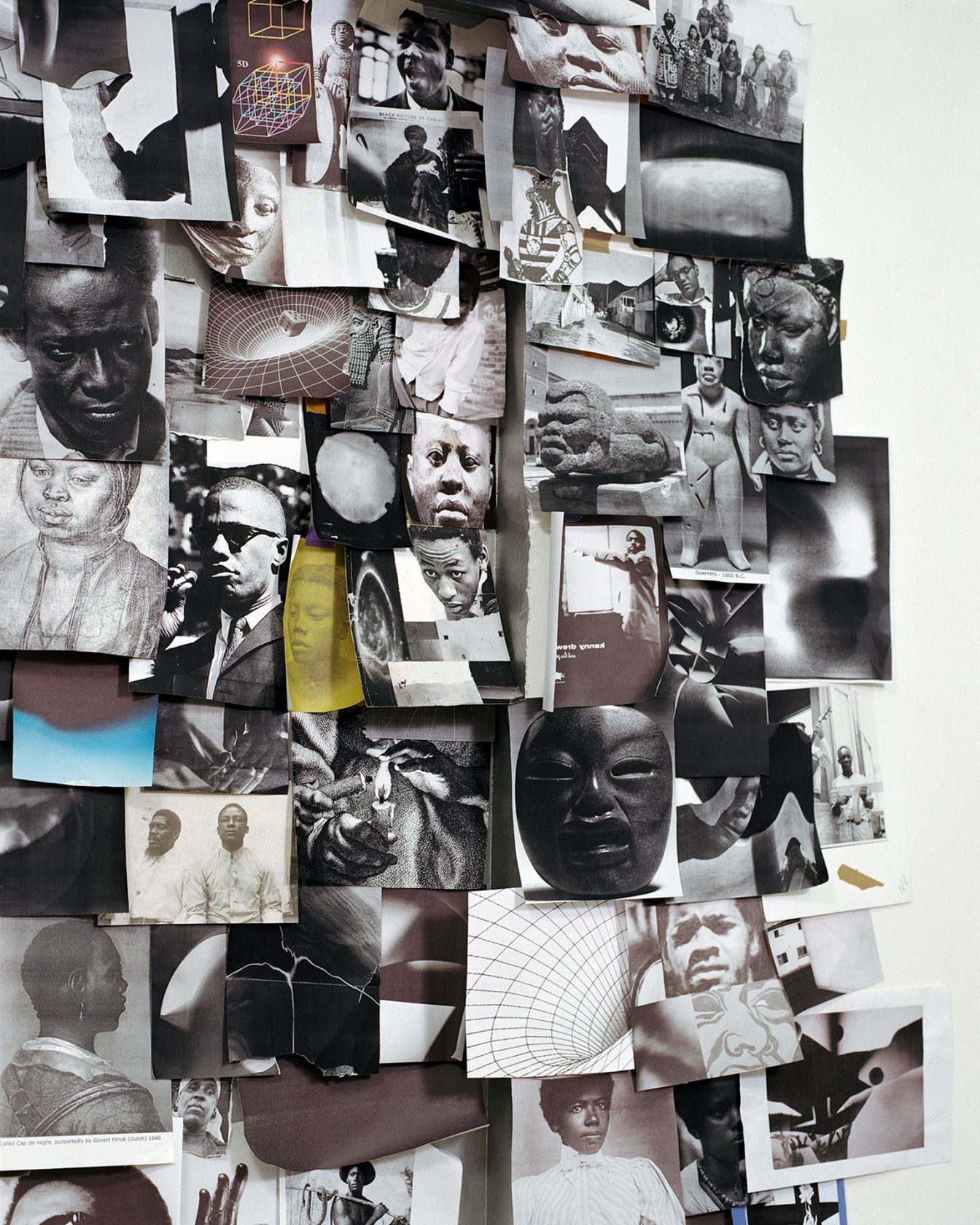

They questioned, for example, how they could expand what is possible within the museum. Could they temporarily turn the space, physically embedded in the guarded art temple, into an artist studio, in all its messiness, they wondered, while simultaneously thinking up and implementing ways to work around the many museum restrictions that lay in their way—adjusting their strategies as they went on. This question culminated in the three iterations of To be determined, where three artists at a time moved their studio practice into the museum, even being permitted to stain the invaluable, heavily protected wooden gallery floor in doing so—not an insignificant achievement on behalf of the Buro team. As an editor, I did not only want to show the outcome, the three open studios, but also the story that preceded it.

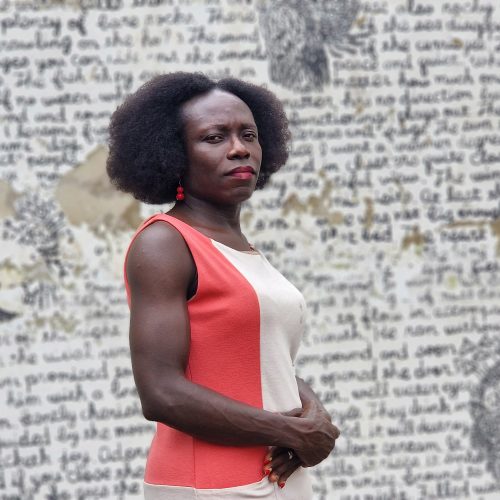

In addition to exploring what they could do in a practical sense, the space was also continuously studying its ethical and conceptual purpose: which instruments can be wielded from within an institution’s belly while retaining one’s own vitality? What curative will the host be willing to swallow? The process of fundamental questioning, reimagining, implementing, while grieving its very need—unfolded daily, over the course of three years. The emotional weight of this task is profound, especially against the backdrop of institutional self-medication that had initially carved out the project space. For those who, through heritage or experience, mournfully felt the harm that their taking up space was trying to salvage, the work demanded its own form of walking softly on earth. Research can soften the personal impact of such labour, though never erase it. This spiritual exhaustion is something we did not want to hide from the reader, and it is among others discussed in the book in conversation with Yvette Mutumba and Tina M. Campt¹.

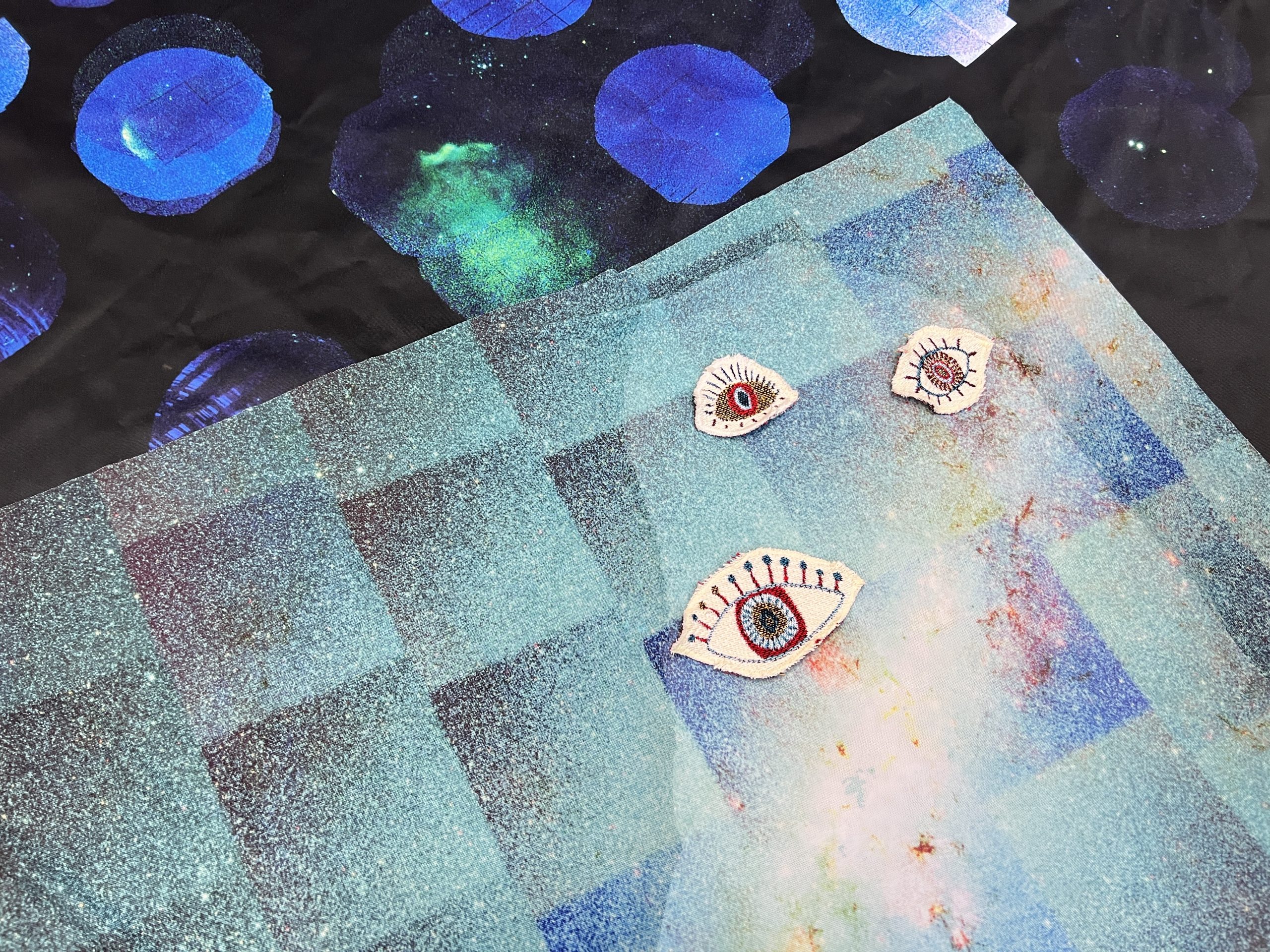

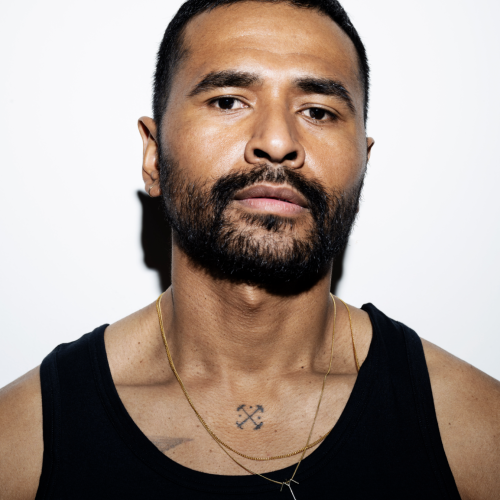

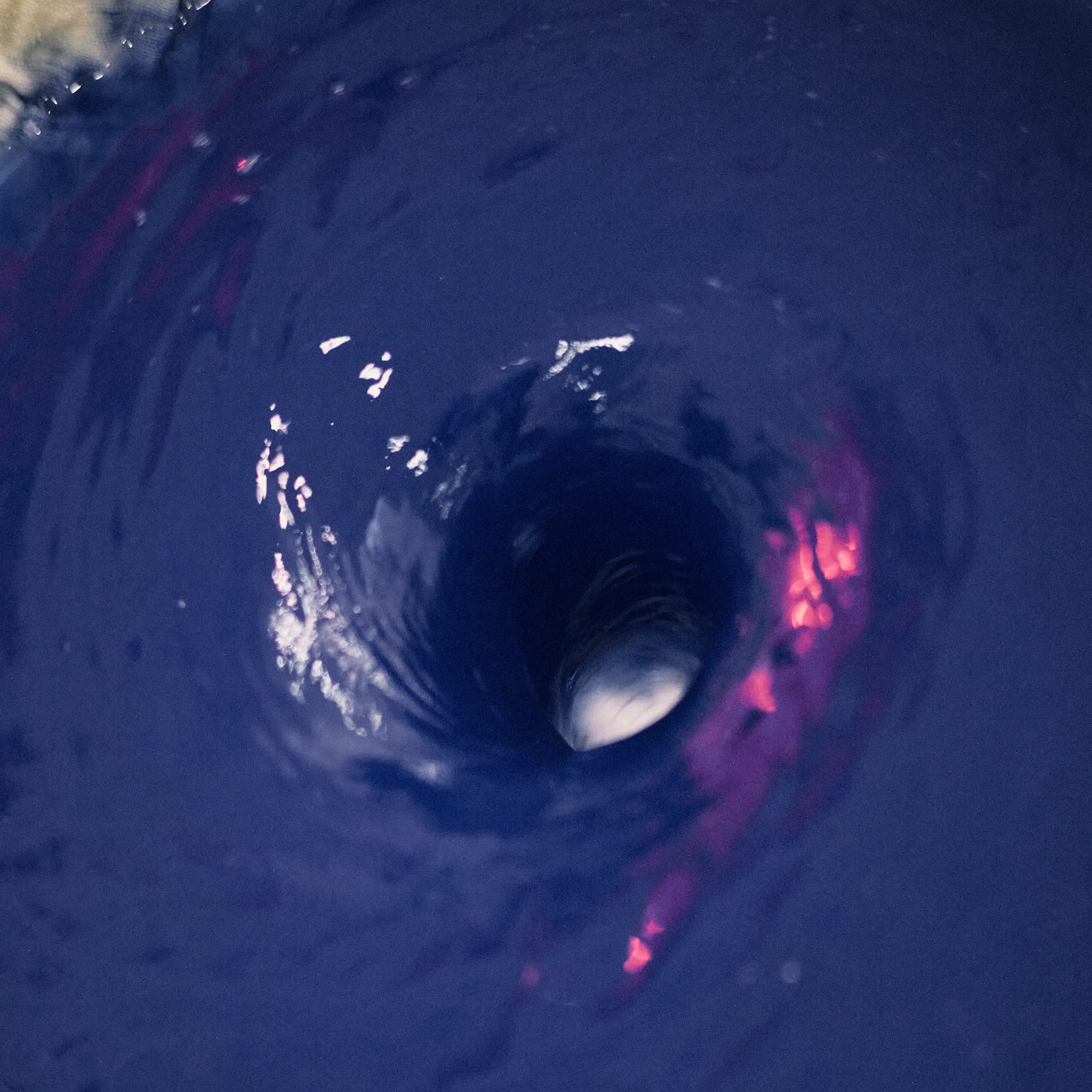

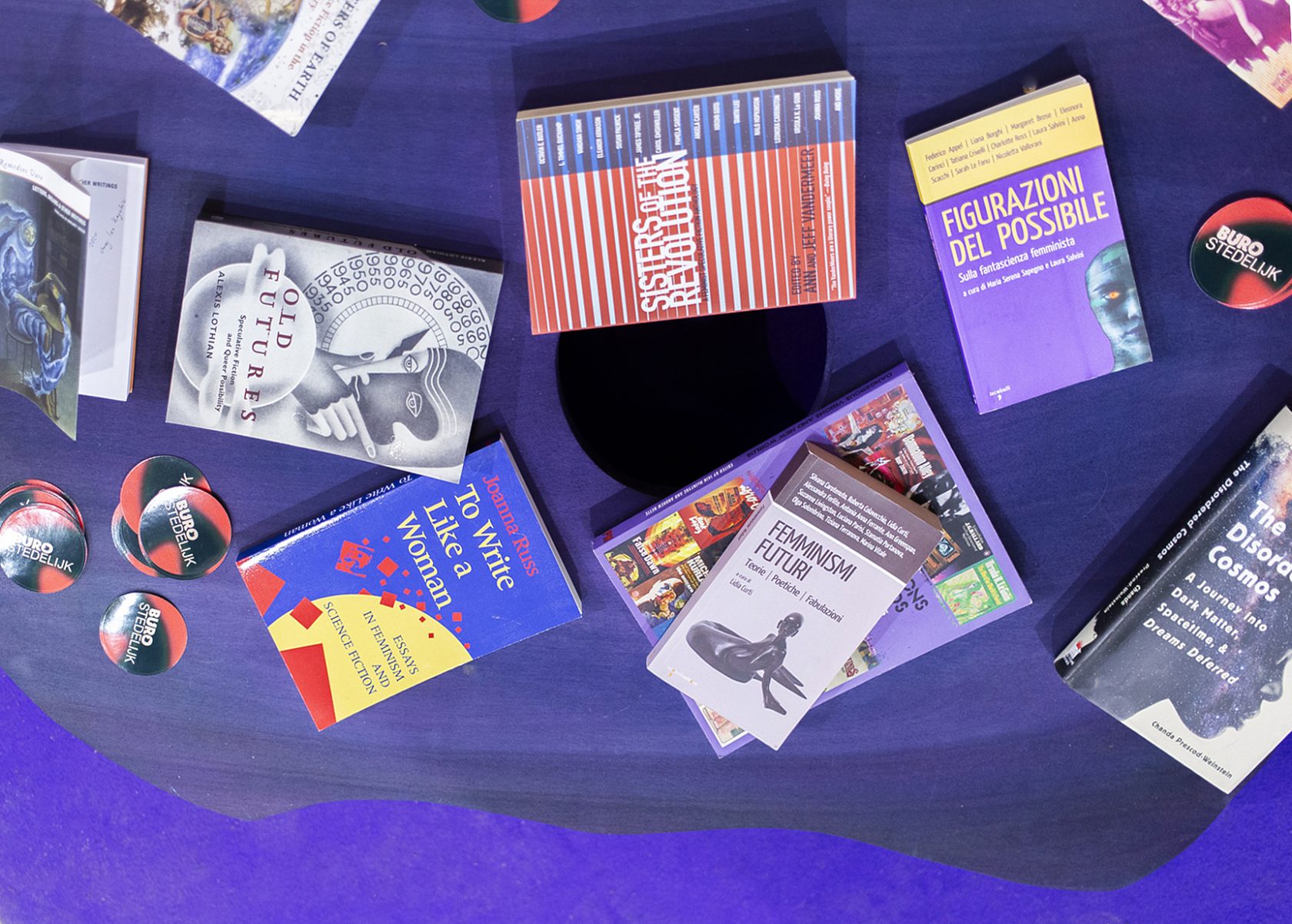

While vulnerably sharing some of the workings of the soul was intentional, the publication project as a whole consciously sought opacity—a refusal of the expectation, in this case of a book, that it should reveal, define, or make wholly transparent. Following Édouard Glissant, the publication upheld opacity as a right: the right not to be fully understood, the right to remain different, the right to exist in relation without exposure². This was crucial for feeling safe while bearing the spotlights of being inside the museum while trying to do things ‘differently’. One of the ways in which this choice is expressed in the publication is through its dialogical emphasis. The many conversations in the book do not seek to unveil essence but to witness relation—to attend to voices engaging, misaligning, finding each other, questioning. Opacity surfaces visually as well: in the cover’s textured veil, referencing the obscured windows of Buro Stedelijk, here adorned with work by Kevin Osepa.

The dialogical emphasis of the book was also a way to express Buro’s commitment to co-becoming, or as Donna Harraway termed it, sympoiesis: “making-with” or “becoming-with.” Sympoiesis resists the notion of autonomous, self-contained systems; instead, it attends to networks of mutual implication, relational ontologies, and worlding-with. As Haraway writes, “It matters what matters we use to think other matters with; it matters what stories we tell to tell other stories with; it matters what knots knot knots, what thoughts think thoughts, what descriptions describe descriptions, what ties tie ties.”³

This relational lens mirrors not only the deep collaborative intentions behind Buro’s programming, which co-became together with no less than 250 collaborators, but also the editorial responsibility of retelling such work. How one historicizes matters and showing that Buro is not a functional part of a greater whole that subsumes it, but an actor in a relationship of differential becoming⁴—a node within a dynamic system of making-with—was crucial for the book to live, too. This is why, from the outset, the book was not imagined as a retrospective artifact but as a living companion to the work that grew through collaborations fostered over time, creating an extended network of people who were given the power of making-with.

Interestingly, recent scholarship on participatory action research has identified building networks, cultivating critical communities, and redistributing power as key components to successfully counter obstacles that researchers invested in creating social change may come across, as they grapple with challenges such as mismatches in institutional infrastructure, risks of co-option, and power inequalities.⁵ Through its commitment to making-with, Buro had built such self-protection into its founding principles: their research-by-doing practice from the outset was to both question and grow in dialogue with an expanding community of collaborators, empowered to cocreate. Another factor that the above research identified was the importance of critical (self-)reflexivity. A keystone of our editorial vision, reflexivity is conveyed through the invitation extended to several collaborators—from artists, lecturers, board members, to producers—to reflect on their collaboration with Buro.

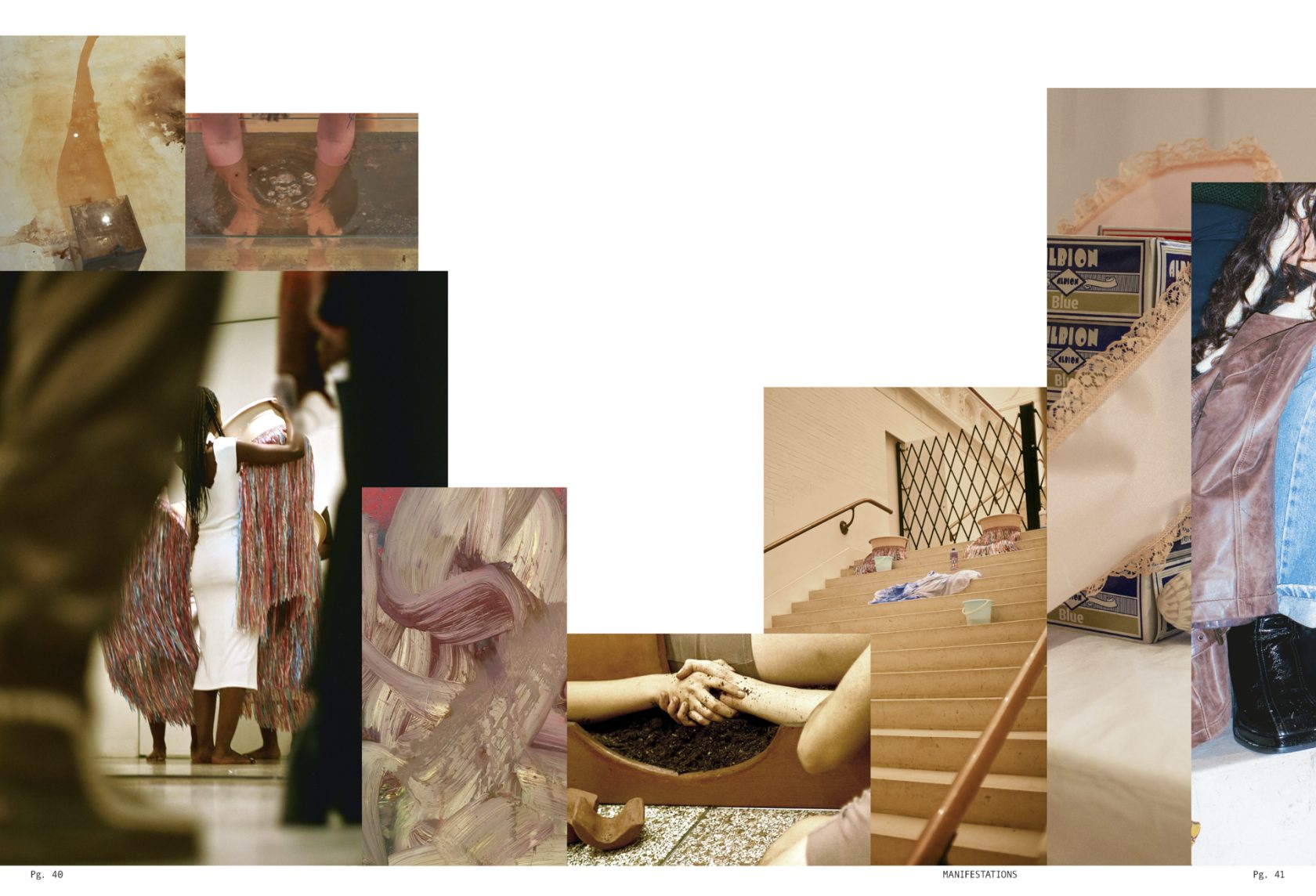

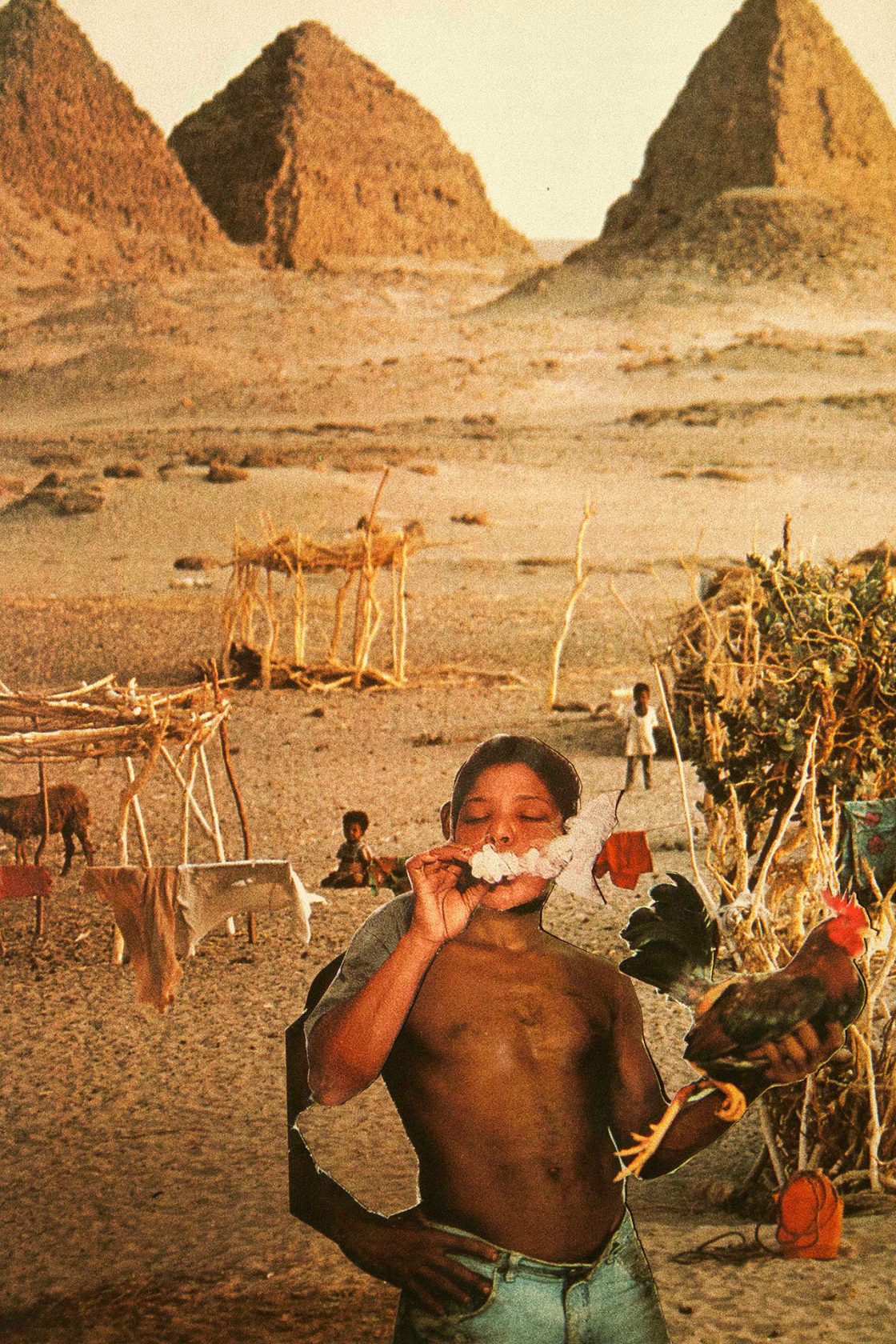

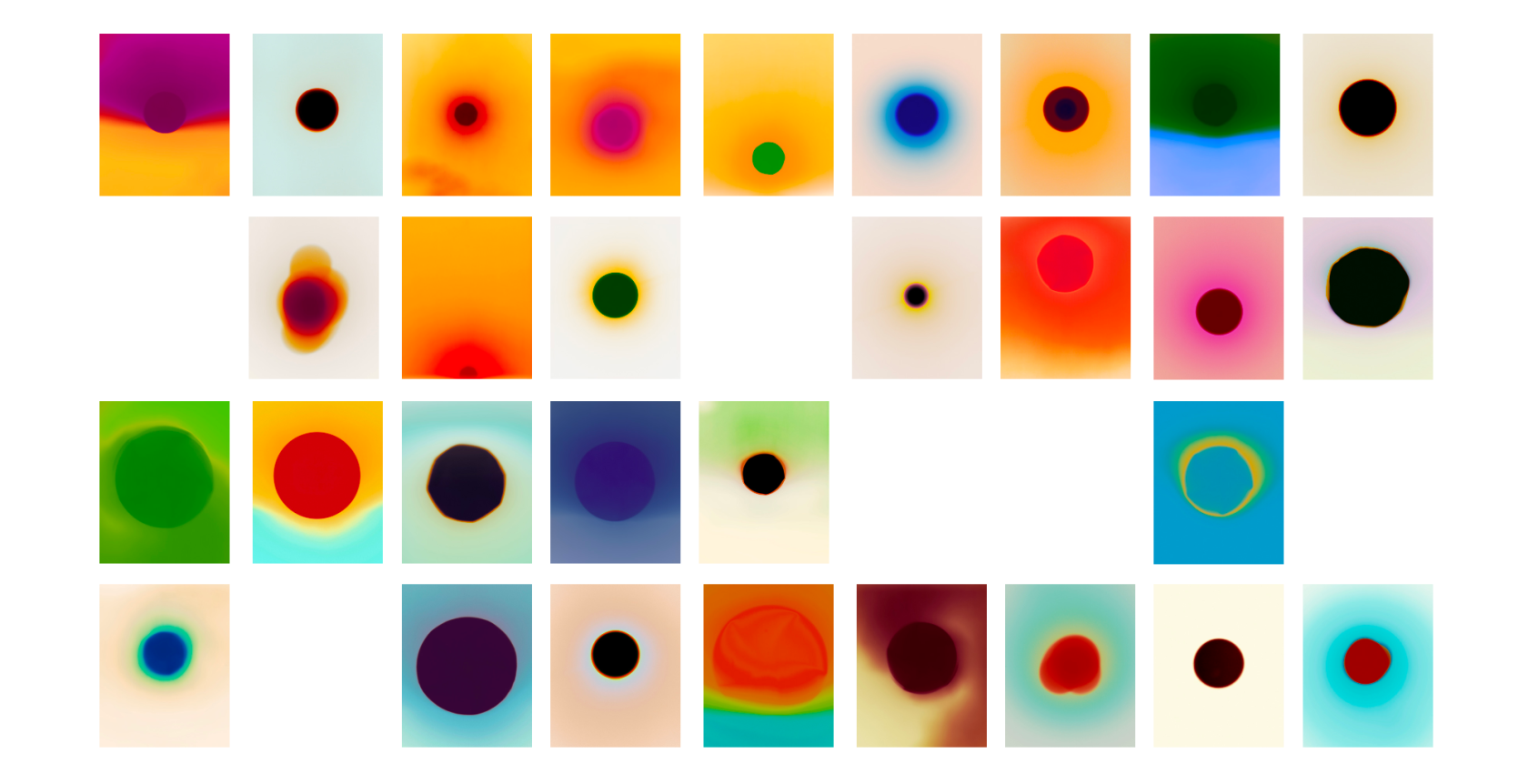

To create a visual world that breathes this attentiveness to co-becoming, to self-reflective action research, opacity, and the power of critical storytelling graphic designer Frederique Gagnon chose to approach the book design through the lens of Ursula K. Le Guin’s ‘The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction’, a 1986 essay that reflects on the stories we tell, and how we tell them. Rejecting the heroic, linear, conquest-driven narrative, Le Guin imagines storytelling as gathering: containers holding what is collected, carried, retold. She draws on the idea of the earliest cultural invention: ‘A leaf a gourd a shell a net a bag a sling a sack a bottle a pot a box a container. A holder. A recipient.’ The cover’s netted texture therefore does more than protect its contents from transparency; it shows that the book sets out to gather and hold together. The image spreads break many art publishing conventions by letting the pictures drop to the bottom of the pages—overlapping in an anarchic tangle—without apparent order, dropping down while held safely within the carrier.

The title—“we need to relearn how to walk softly on earth”—is a quote by author Ailton Krenak, the first Indigenous person elected to join the Brazilian Academy of Letters. In the respective interview, he emphasized that “no one is a separate cocoon in the cosmos living this experience alone”, connecting appreciation of the arts to the importance of reconnecting with the ecosystem around us. This co-becoming with our surroundings in the deepest sense—this grounding, collective, and self-reflective work—is the sustenance we need to allow ourselves the brave frailty needed walk softly on a planet also inhabited by people—regal or otherwise—whose love of art does not prevent them from daily sacrilege. As an investigation of both healing and mourning, institutionally and spiritually, of making-with, Buro Stedelijk’s work—and the storytelling gathered in this book—both questioned while protecting itself through a rich celebration of entanglement, opacity, and relation.

Curating, research, and publishing can all become forms of trying to walk softly: attending to what is already there, to what has been harmed, to what is cautiously emerging; moving with care while looking darkness in the eye; building containers rather than monuments; creating through companionship rather than mastery. This book—our carrier bag—is an offering to that ongoing co-becoming.

¹ How we Made Noise, p. 102 (Mutumba) and p. 140 (Campt).

² First expressed in his Caribbean Discourse (1981) and readdressed in his Poetics of Relation (1990).

³ Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble. Making Kin in Chthulucene, 2026. Durham: Duke University Press, p. 12.

⁴ Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble. Making Kin in Chthulucene, 2026. Durham: Duke University Press, p. 12.

⁵ Flora Cornish, Nancy Breton, Ulises Moreno-Tabarez, Jenna Delgado, Mohi Rua, Ama de-Graft Aikins, Darrin Hodgetts, ‘Participatory Action Research’, in: Nature Reviews Methods Primers, vol. 3, no. 34 (2023).