#67 FLIGHT

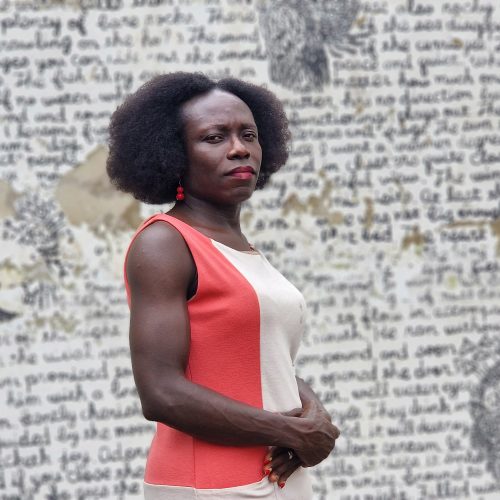

An accompanying essay to 'Manifestation #58: The Black Film Critic Syllabus', by Fanta Sylla

This program of short films assembles three generations of Black and women visual artists, Ngozi Onwurah, Christelle Oyiri, Mati Diop, and Manon Lutanie, respectively born in the sixties, eighties and nineties. The selection seeks to register a certain recent history of art and cinema, as well as an evolution of Black female representation behind the camera and on-screen through the years. Though formally distinctive, I like to believe that these films dialogue with one another through recurrent themes, motifs, and silhouettes: childhood, death, Black girlhood. The heavy presence of music, whether in the score or as an integral part of the subject, cements their fellowship. Music is the cardinal theme around which I wished to articulate this program. I have always been inspired by the relationship between sound and the visual arts, and the way Black artists have made the two art forms dialogue with one another.

The selection begins with Flight of the Swan, released in the year of my birth: 1992. Directed by the British-Nigerian filmmaker Ngozi Onwurah, Flight of the Swan tells the story of a young Nigerian girl who travels to England eager to dance in the white-dominated arena of ballet. The world (her fellow mainly white dance peers) sees her desire as an affront and thus opposes her through mockery and exclusion. Onwurah, who is mixed-race and the child of a Nigerian immigrant, explores the theme of liminality, through a young protagonist who is asked to choose between her Nigerian roots, and with that a certain essentialism, or a betrayal of the self by forcing herself into a white, foreign world that does not want her. Music, such as the polyrhythmic African drumming beat that starts off the film and is contrasted with the familiar orchestration of Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake, conveys the protagonist’s identity oscillations. Here art becomes a space in which the director solves, by way of remixing and juxtapositioning, the unjust assignations young Black, immigrant, and mixed-race girls must experience in a social world that is often too limited to integrate and honor their multitudes, paradoxes and contradictions.

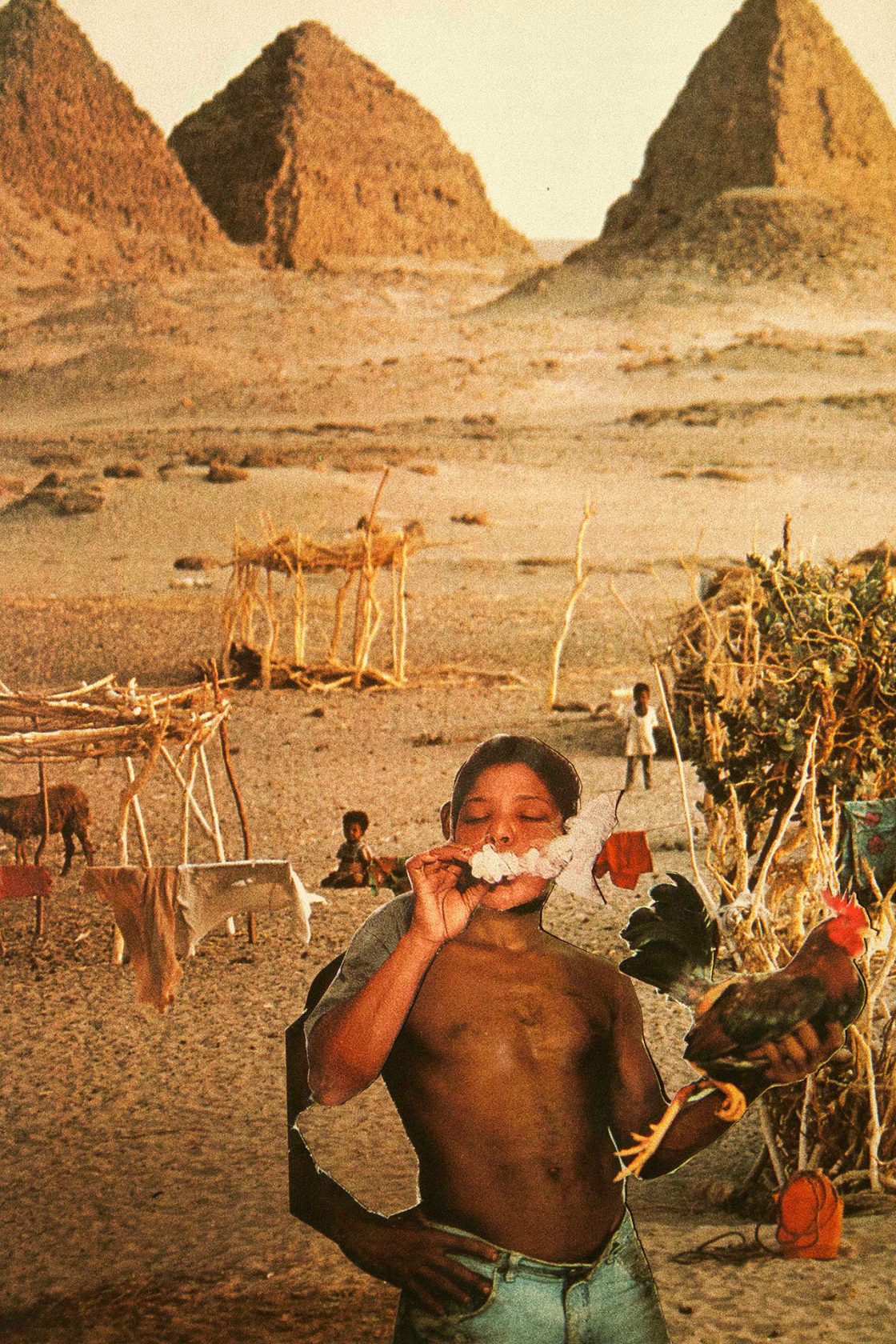

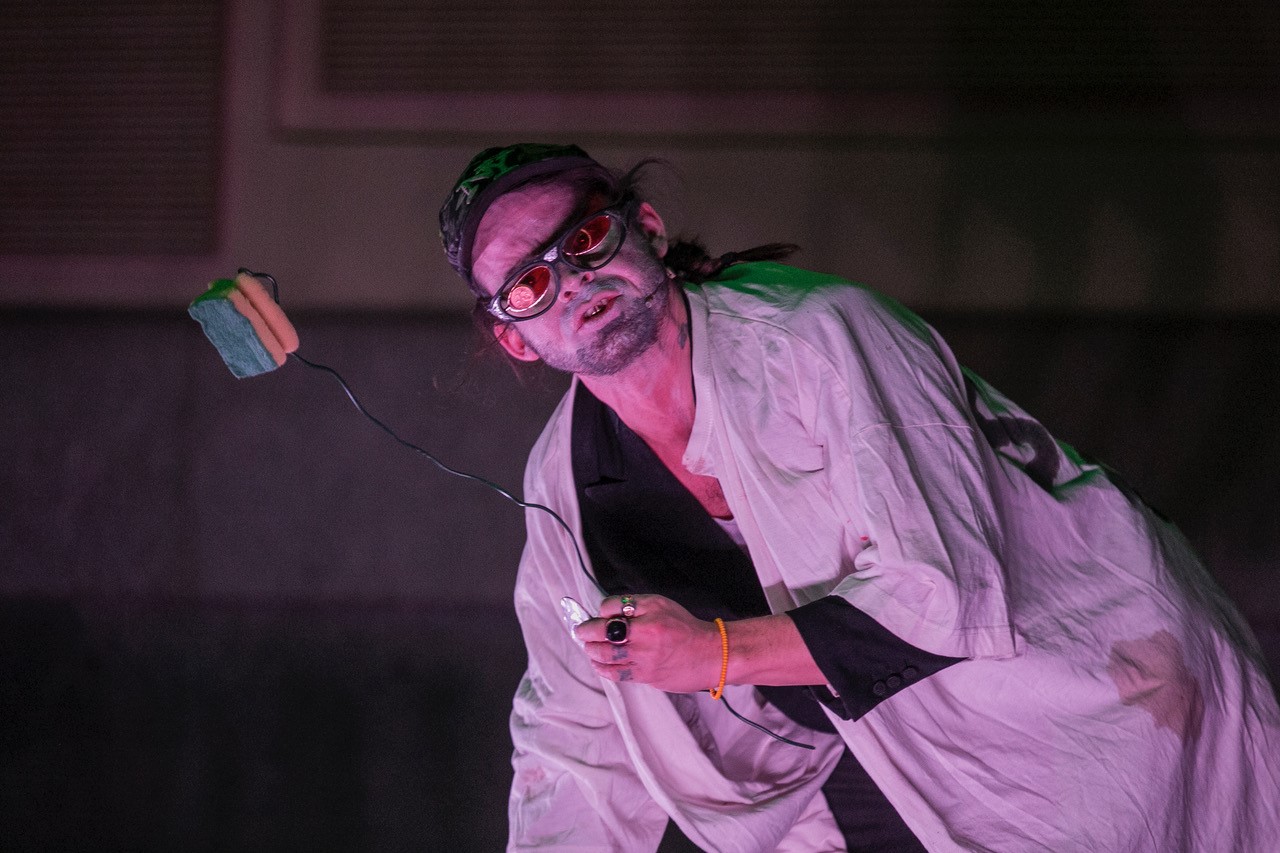

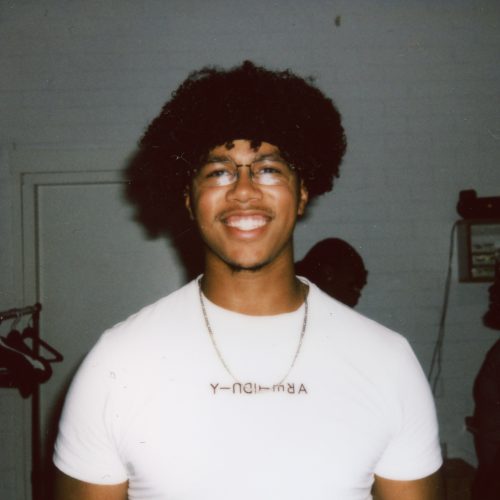

Opposing the simplification of true crime narratives about the death of rappers, HYPERFATE centers around the melancholic stream of consciousness and metaphysical musings of the author, the French-Ivoirian-Caribbean filmmaker, video artist, and producer Christelle Oyiri (aka Crystallmess). Again, the silhouette of a little Black girl appears, in this case the director herself. Her voice narrates a disillusion: that of a young Black French woman, music writer, and rap lover, who is confronted by the tragic fate and often death of mainly Black American rappers – from Tupac to Pop Smoke and Migos’s Takeoff. After the cacophony of Onwurah’s short, we are welcomed by an ambient score into what is essentially a funeral procession in the form of an art video. The director films herself in a car that goes through urban American neighborhoods. She mingles her own stories, both personal ones and those of the men in her family, with those of the artists she grew up to admire. Here music serves as a cosmic standpoint from where to explore philosophical musings on fate and its intersection with race. HYPERFATE is a station where the spectator stops for a first-person, intimate, experimental narrative.

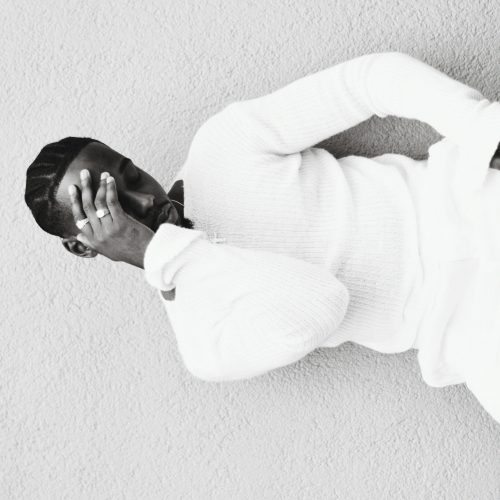

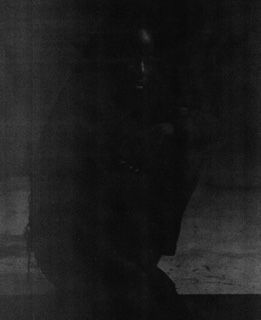

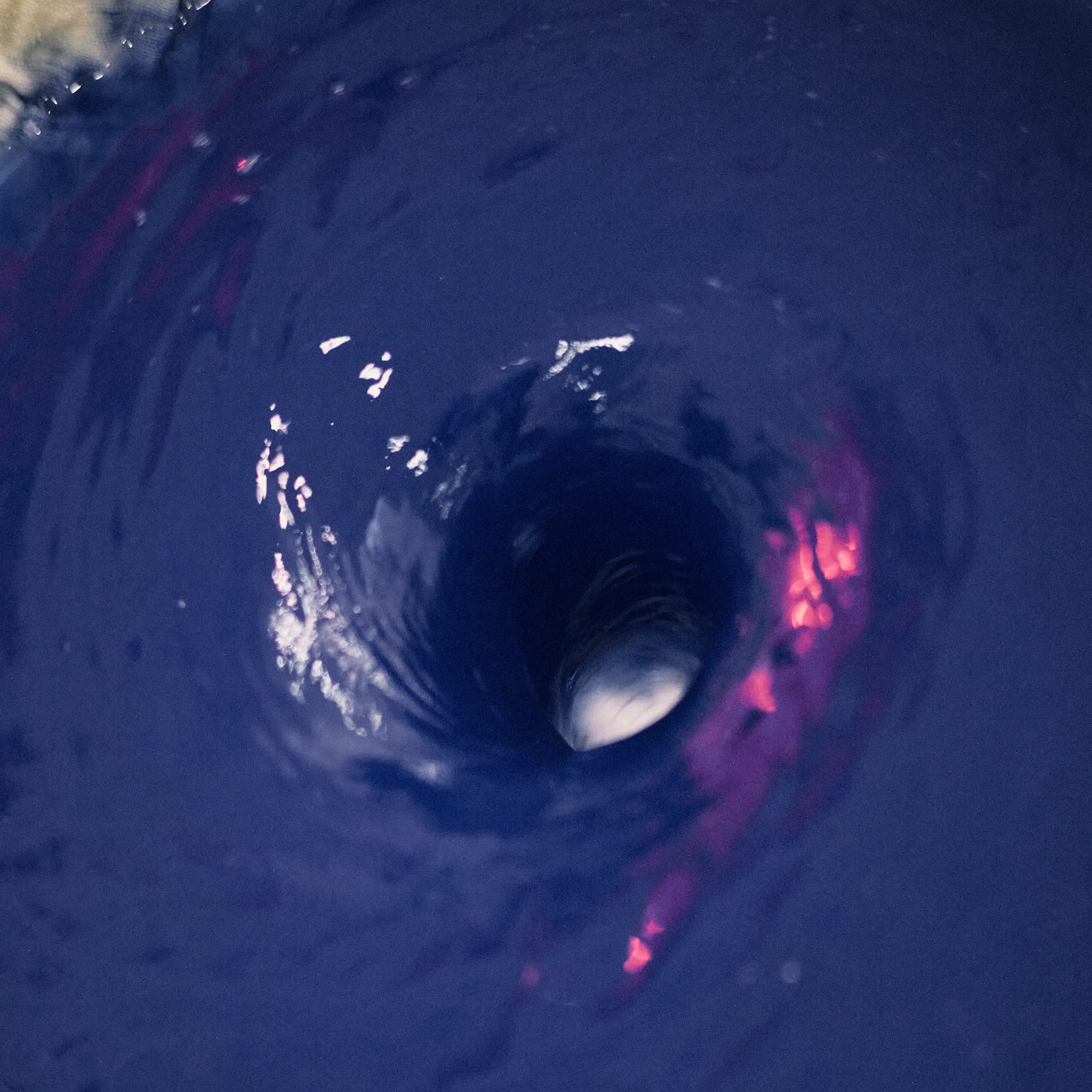

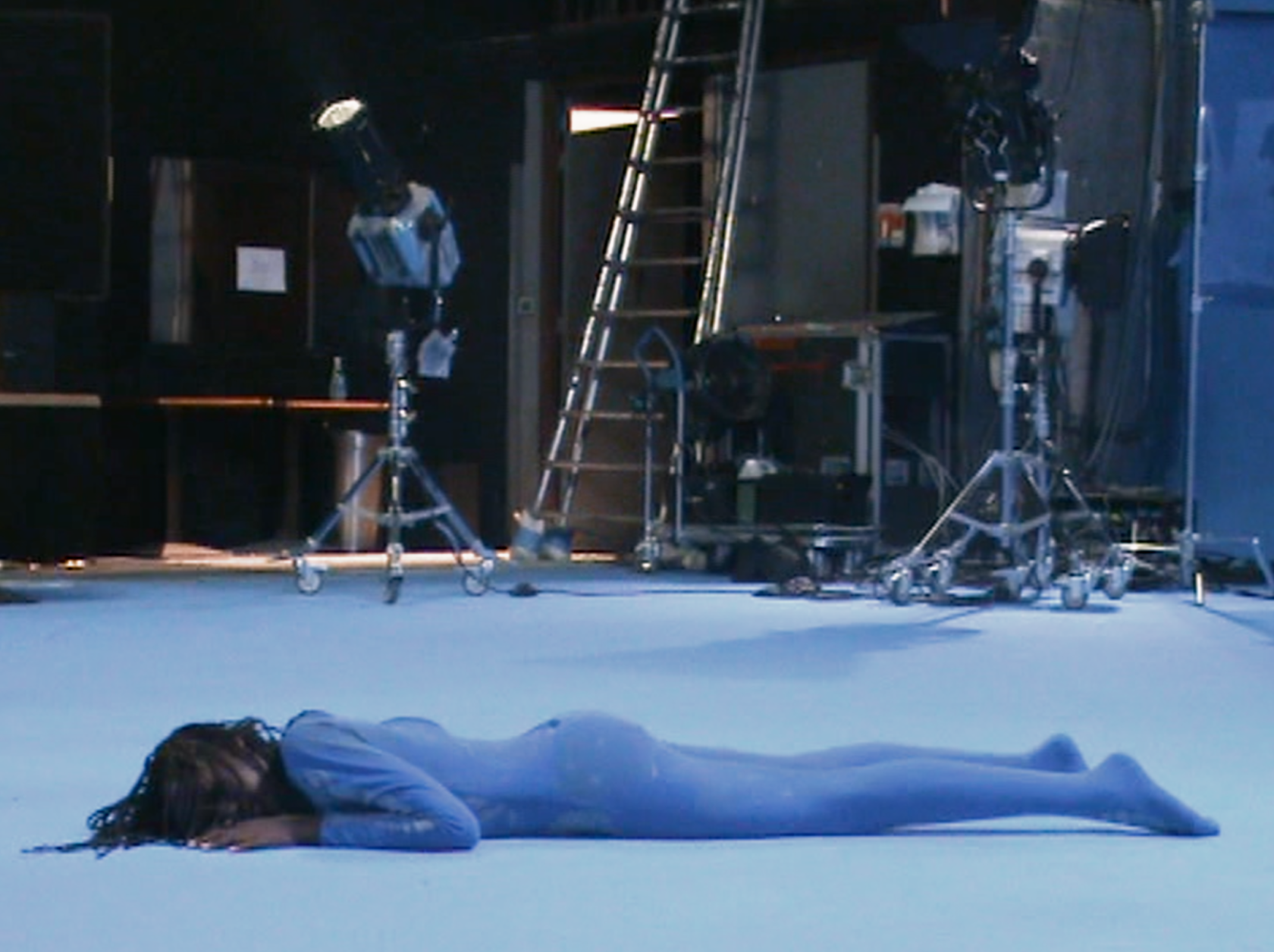

Finally, the protagonists of French filmmakers Mati Diop and Manon Lutanie’s Naked Blue and The Flight of the Swan can be seen as long-distanced sisters, separated by both space and time, but both united by the swells of classical music. Oumy, a real-life ballet dancer, though, exists in a strange blue world, seemingly somewhere in outer space. Then the infrastructure of a studio somewhere in France is revealed. She owns the space and commands the camera. Wearing a uniform marked with a white skeleton, she faces her own reflection in a tall mirror with a youthful arrogance. The directors track her various states of minds through an ever-morphing choreography. The variations of the orchestral score, composed by Devonté Hynes and performed by the Budapest Scoring Orchestra, that accompanies her movements and her trance, take the film into fantasy and often into near-horror realms of imagery. Both actress and subject of study, Oumy Bruni-Garrel inhabits the filmic space in a way that is rarely seen in French cinema and video art. Many times, her appearance and reflections are distorted by the shift in lighting or a mirror effect. Over the blue backdrop, with the lighting turning Oumy into a black silhouette, erasing her distinctive traits, the main character is charged with a menacing aura.

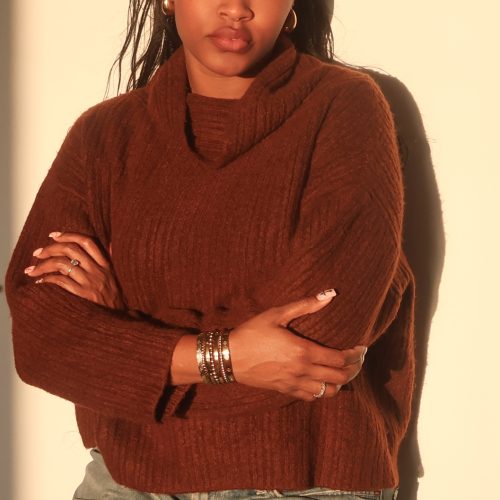

Naked Blue closes a triad of films that sought to capture and register rare characterizations of Black girlhood and its many emotional states: melancholy, playfulness, sadness, anger, hope and elation.

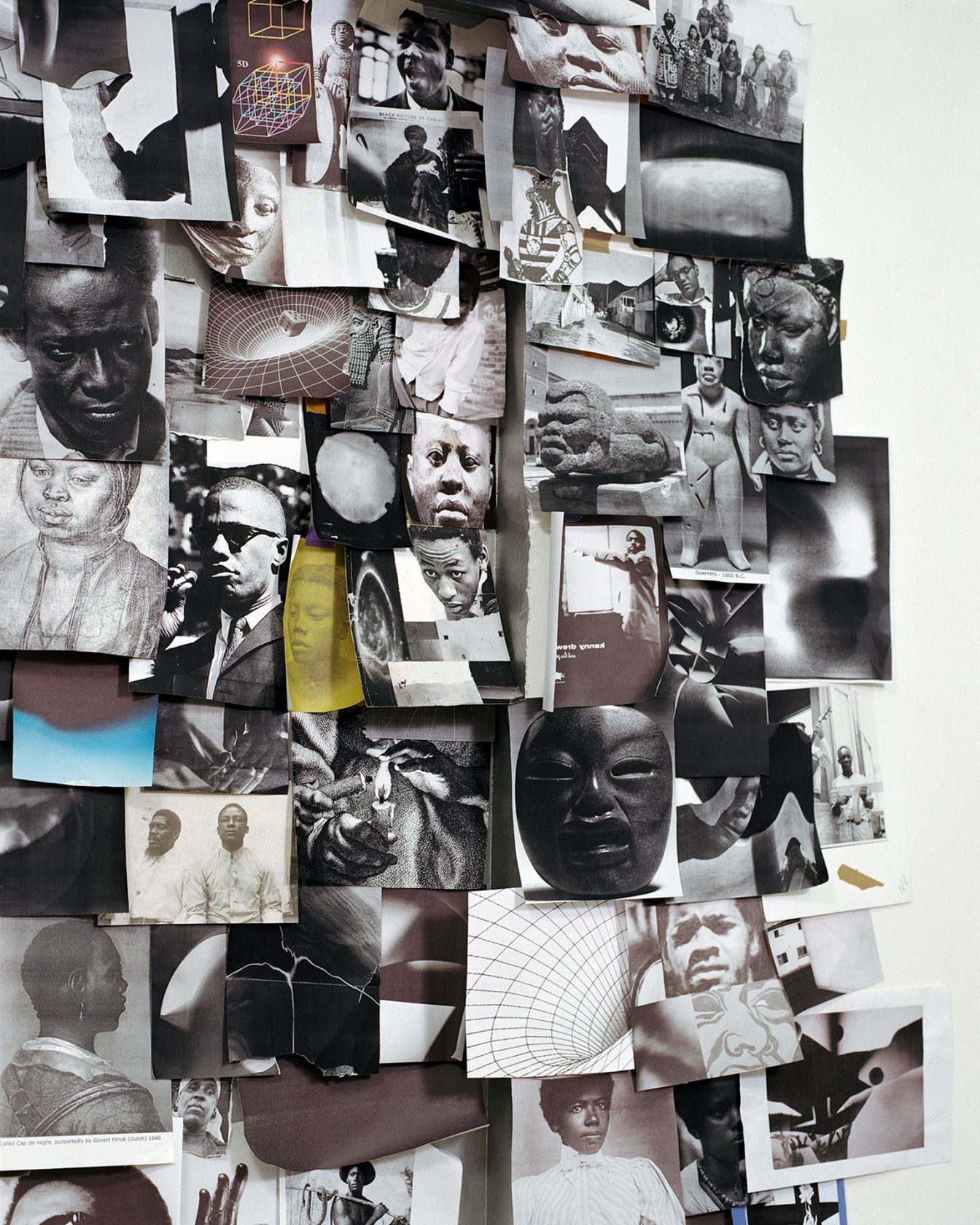

When I entered the world of cinema, going from the observant, “passive” position of Black spectatorship to the responsive practice of film criticism in my early twenties, I was obsessed with the desire to expand my own and my readers’ inherited notions of what cinema is and could be. When it came to images of diasporic Blackness the parameters of mainstream cinema were too restrictive; reality was much more abundant than what the screen was projecting back to us. Cinema could not be, just this. Inspired by the prose of the late Black American cultural writer, theorist and poet, bell hooks, my own writing followed her call to look beyond the mainstream and look particularly to the margins. Independent and avant-garde filmmaking, of course, but also marginalized or less-prestigious audio-visual forms: short films, music videos, vines, memes, video art.

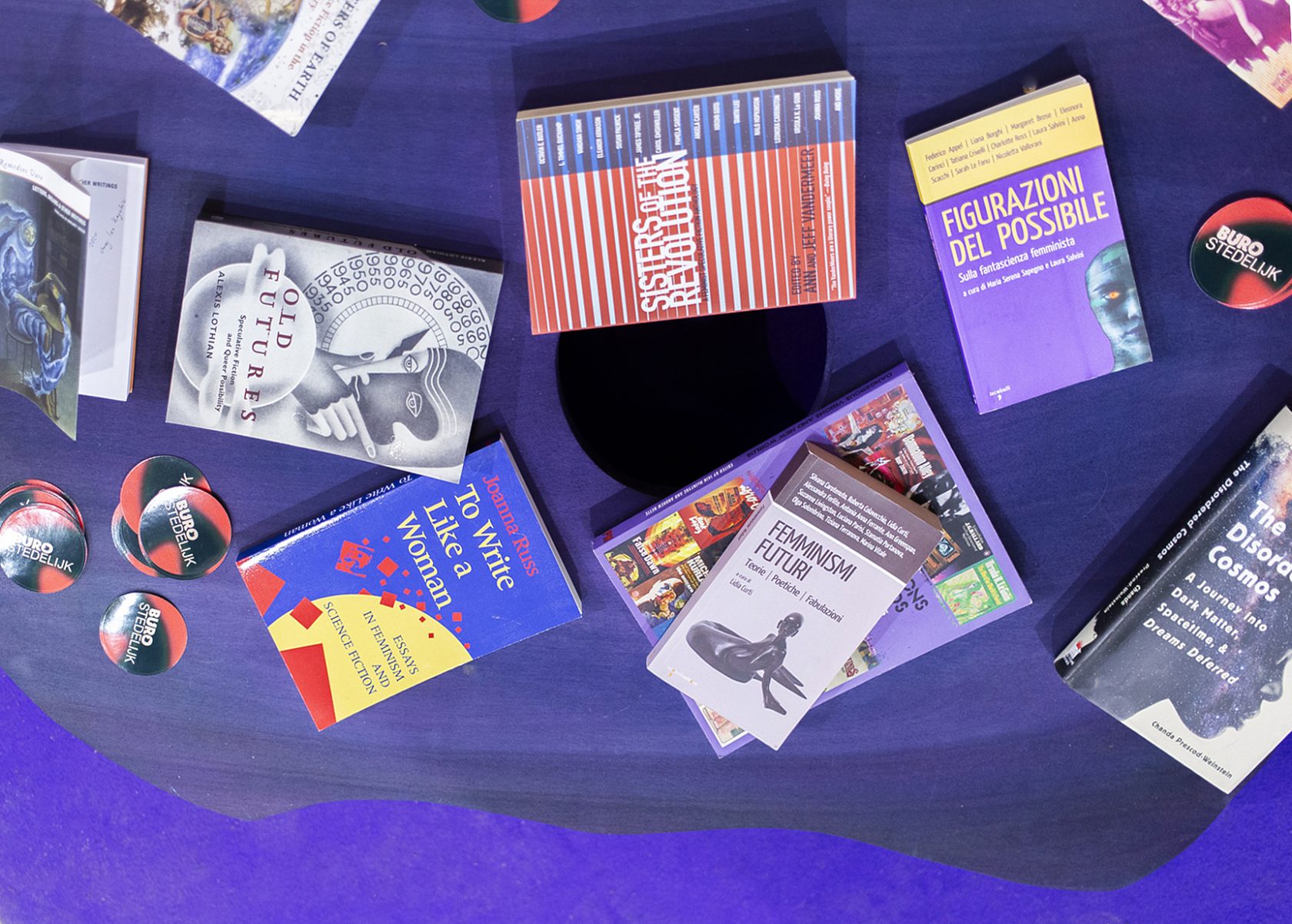

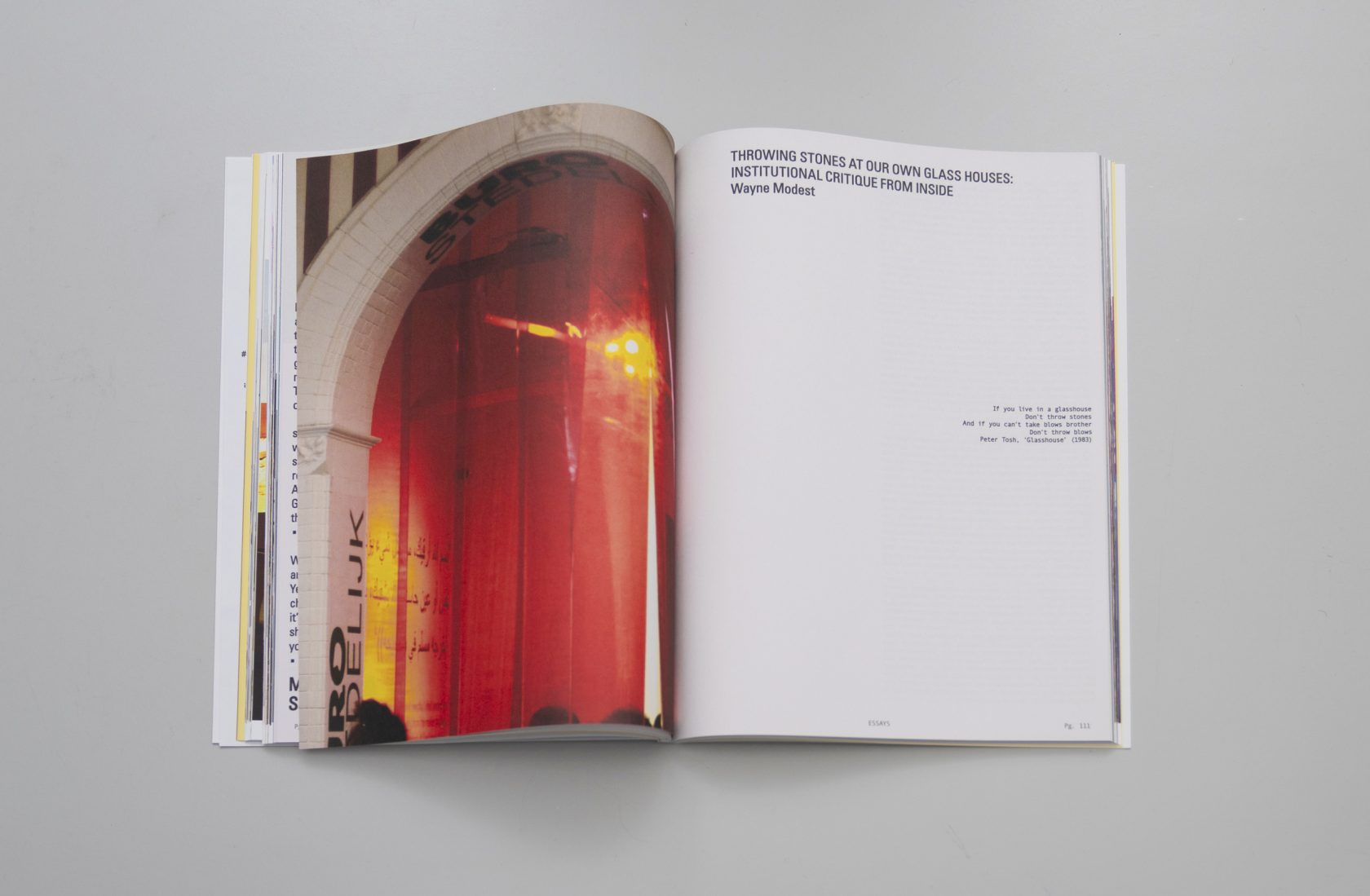

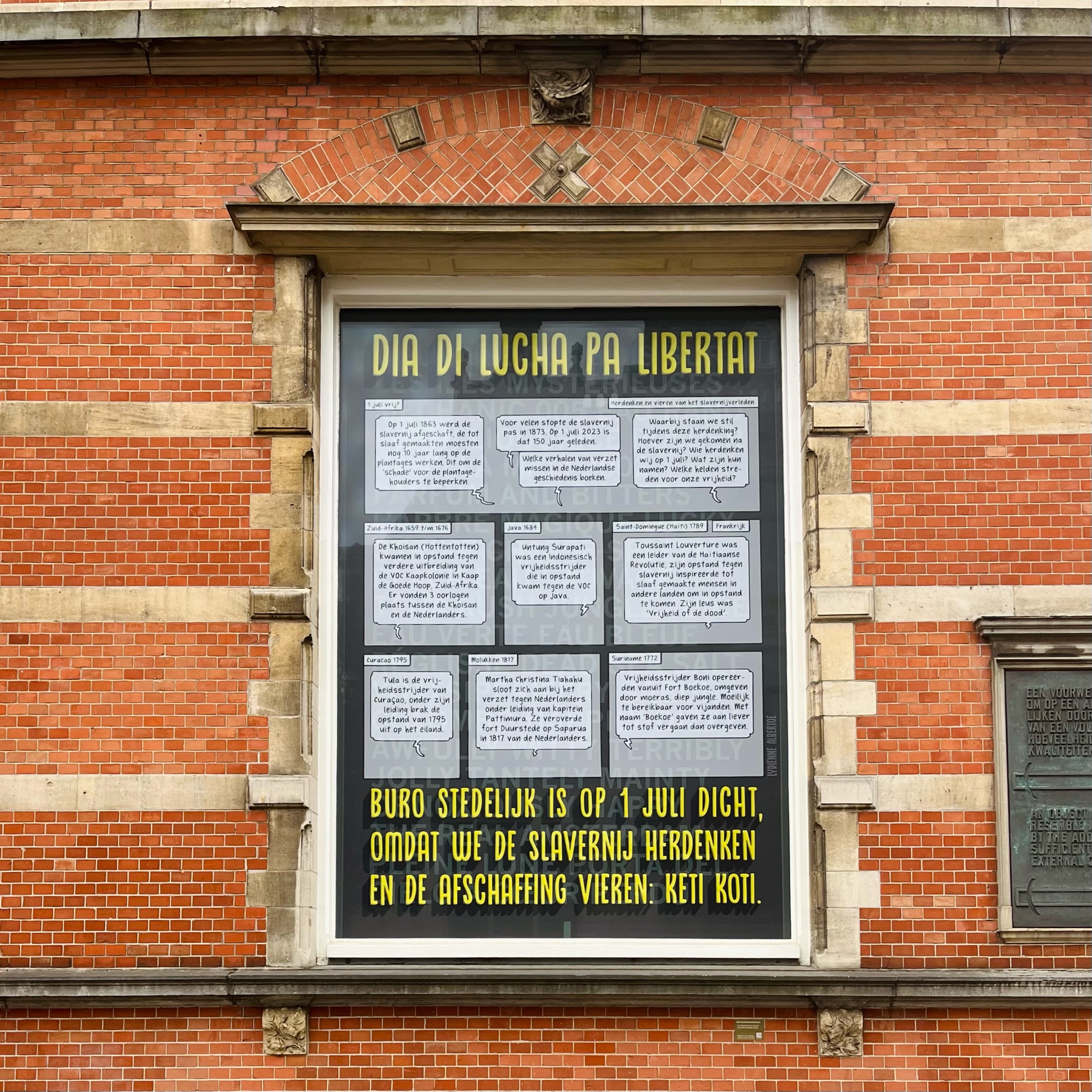

My self-imposed mission was also to move from representational discourse on Blackness, from the consideration of the white gaze as the shaping force of Black representation to…something else. Something to be invented with the knowledge of the past and the rich present of film. When I created The Black Film Critic Syllabus in 2016, an open-access database compiling Black film history and theory references, the objective was to mimic and inspire, in its perpetual updating, a search for expansion. Each reader and future writer was invited to find their personal, idiosyncratic path in the world of cinema and film criticism, to find their own way to write about film. To write from the standpoint and textual references of those authors that they find most appealing, interesting, sensual and exciting.

There is not one way to write about film, just as there is not one definition of what a film is. In many ways, this selection of short films, a combination of video art and narrative films, reflects my own coming of age as a film critic and viewer. It shows how I have been drawn to expansive, chameleonic (Black) artists who transgress categories and genres.