#17 Rehearsing institutional de-scripting: A machine for manifestations

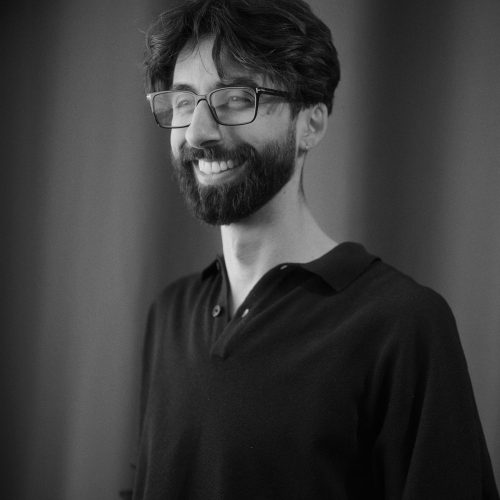

by Setareh Noorani

In early 2024, roughly a year after opening to the public, Buro Stedelijk hit the mark of its 30th manifestation. This milestone prompted a review of the initial spatial design question posed to Jelmer Teunissen and me, along with our response to this question as a design team—while reflecting on the validity of our visions for a cultural institution today. What does the art landscape or even the institutional landscape of Amsterdam, as it sits within the broader context of the Netherlands, need?

The design brief for Buro Stedelijk was formed by mutual understanding and acknowledgment between us, the curators, and the project manager regarding the conceptual motivations and political frameworks of our respective work, as well as the practical restrictions of setting up a new space for art with limited resources within the existing institution, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam.

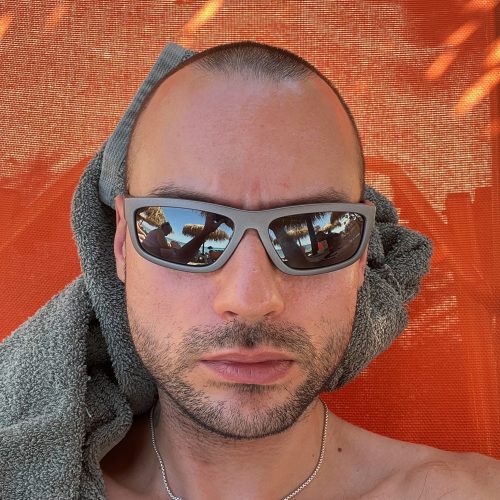

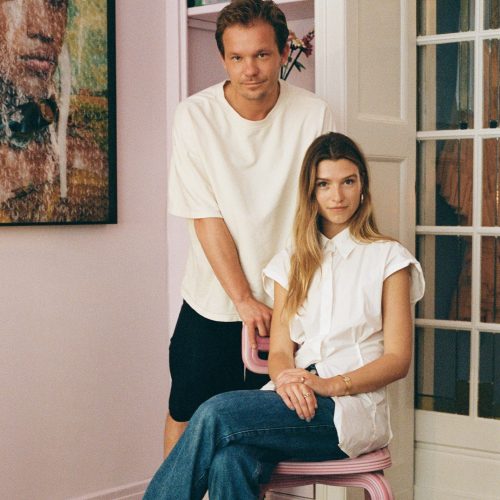

Jelmer, my long-time design collaborator, and I ground our work in an architecture that rehearses spaces for change through the questioning of structures. The concept of rehearsing signifies a continuous process of transition, formulating the various ways out from our position within utopian margins¹: spaces where we practice longing and belonging, crafted in the here and now. We try to operate tools where the systemic meets form. Here, the white cube gallery invites the exercise of individuality. The white cube figures as a supposed tabula rasa, yet this supposition hinges on a deeply rooted tradition of selectively including and excluding certain elements and facets of life to provide an illusion of autonomy to art. This idea is ingrained in a history of scripting spaces, of implicit and explicit staging, and (de)commodification of art. The white paint on the walls of the white cube is a primer in the sense that it primes audiences. Through designing we try to suggest new allyships. We like to create affective environments that hinge on elements being brought in by collaborators, whether a curtain by our friend Matt Plezier in the show at OSCAM or material reuse from local stock at SCRAPXL for our Van Abbe/Dutch Design Week scenography.

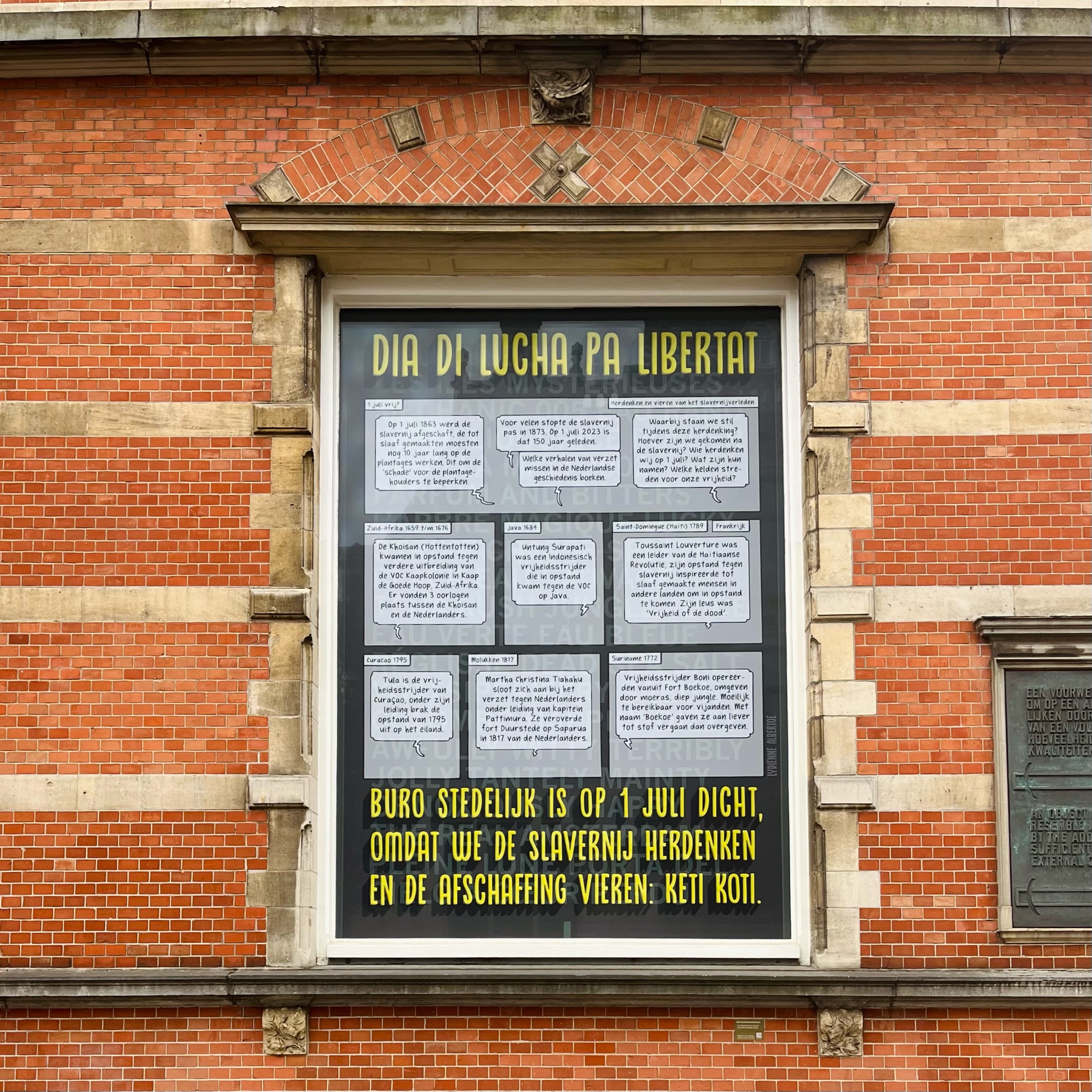

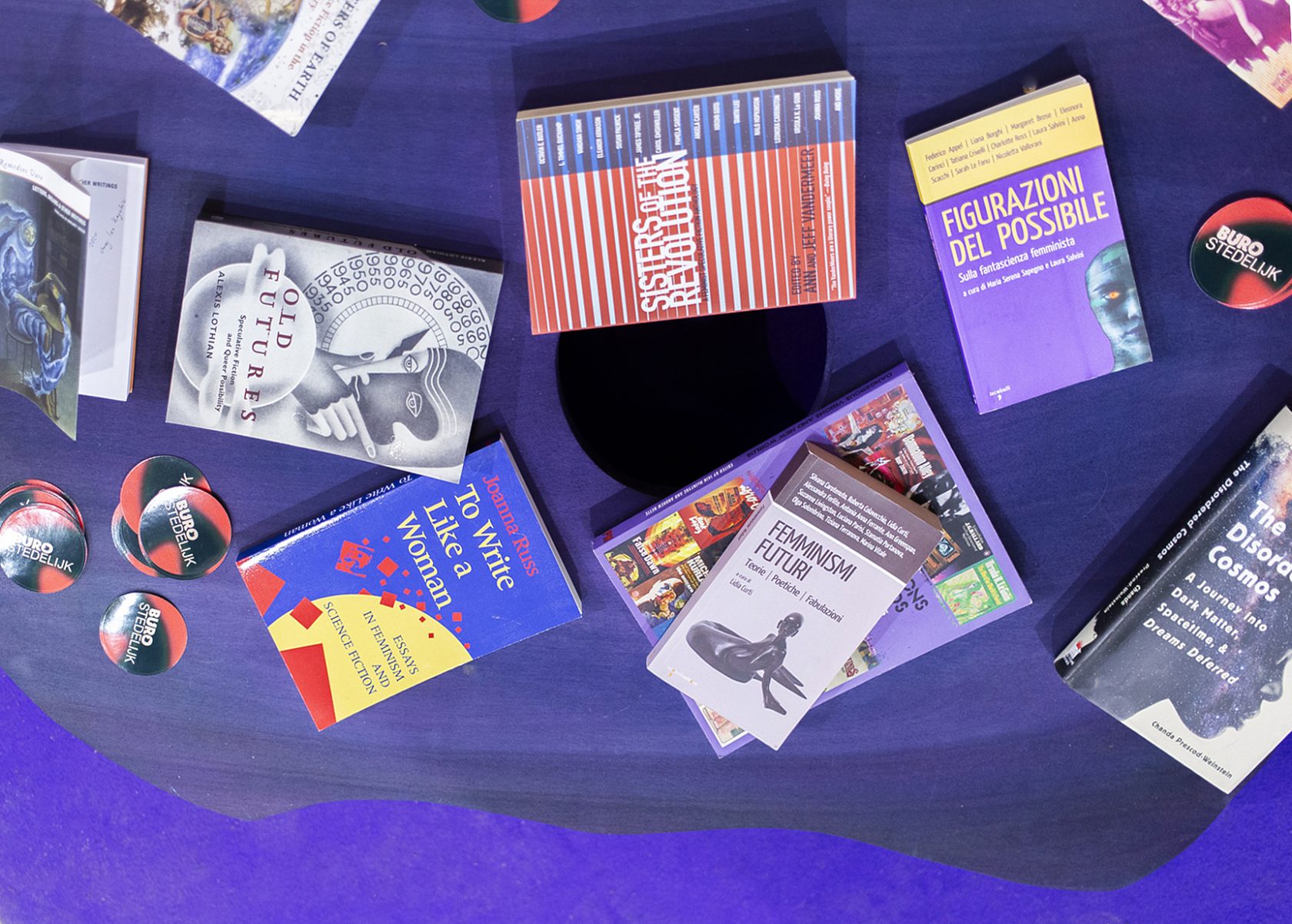

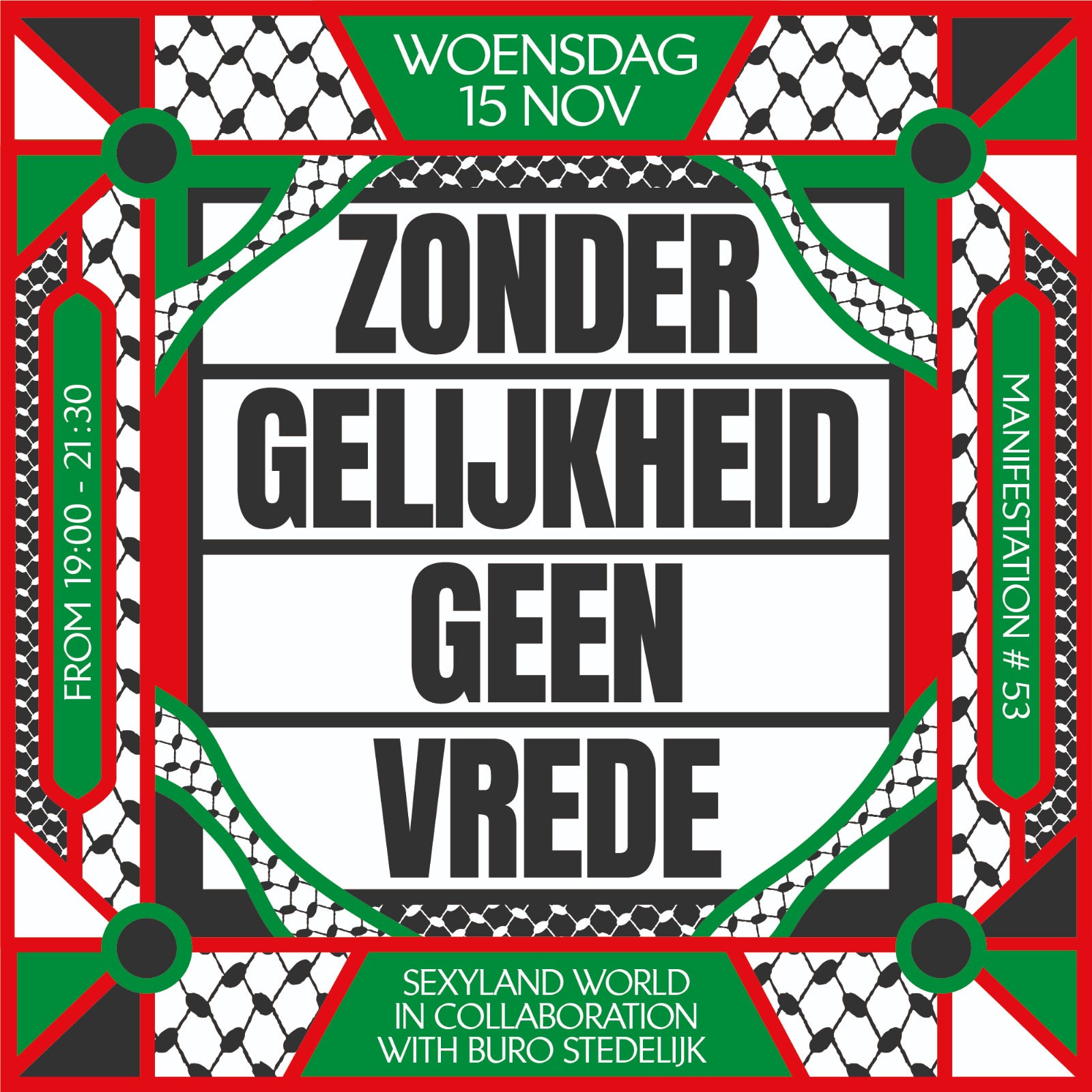

Buro Stedelijk was from the get-go conceived as a new node for beginning-to-mid-career artists to experiment with new forms of work and offer new perspectives to arts and culture audiences locally and nationally. At the same time, Buro set out to stretch the possibility of such and more collaborations – marking the incentive for inspired intervention by a wide range of agents, not only ‘artists’, and interventions that could be seen as convivial activations of the art. These were called ‘manifestations’. The manifestations were to happen in a space still to be negotiated with the current Stedelijk Museum, while some of Buro Stedelijk’s position within the museum and the cultural field was already predetermined by its host and Buro’s predecessor from the 1990s, SMBA (Stedelijk Museum Bureau Amsterdam). There was much at stake, much that could also be read as conflicting and warranted many explanatory, and frankly, quite deep conversations about the new space’s ambitions. For one, the imaging of Buro Stedelijk: should recognisability be the aim, given Buro Stedelijk’s location at the Stedelijk, and how would that balance with the need to remain adaptable to changes in collaboration throughout the ensuing (three) years? What are the forms of ‘credibility’ Buro Stedelijk wants to signal; how would the new space want to ‘institute’ itself? How, on a practical level, would Buro Stedelijk be able to be a welcoming space and a good host; what space for solidarity (with a plurality of bodies) would there be? What do these aspects of entering, moving through, and exiting imply for the economies of generosity and exchange Buro aspired to? These are by all means design questions, the answers to which indicate ways architecture can either assist in the upholding or dismantling of scripts and structures.

A powerful statement could be made by the way space was given and received – from us as designers, to the curators, to the users at large (and vice versa). We captured our response in a ‘spatial statement’, a thinking-with the curatorial framework. What would it mean to design a space that de-scripts itself, and understands its role as a holding space, a vessel that responds as a machine to enable a sense of freedom and access to a diversity of bodies? While clarifying the brief (together), the emphasis for us as architects lay on the vision of Buro Stedelijk as challenging the conceptions of the ‘white cube’ gallery situated in the cyclical pace of art production; an example Buro was literally enveloped in.

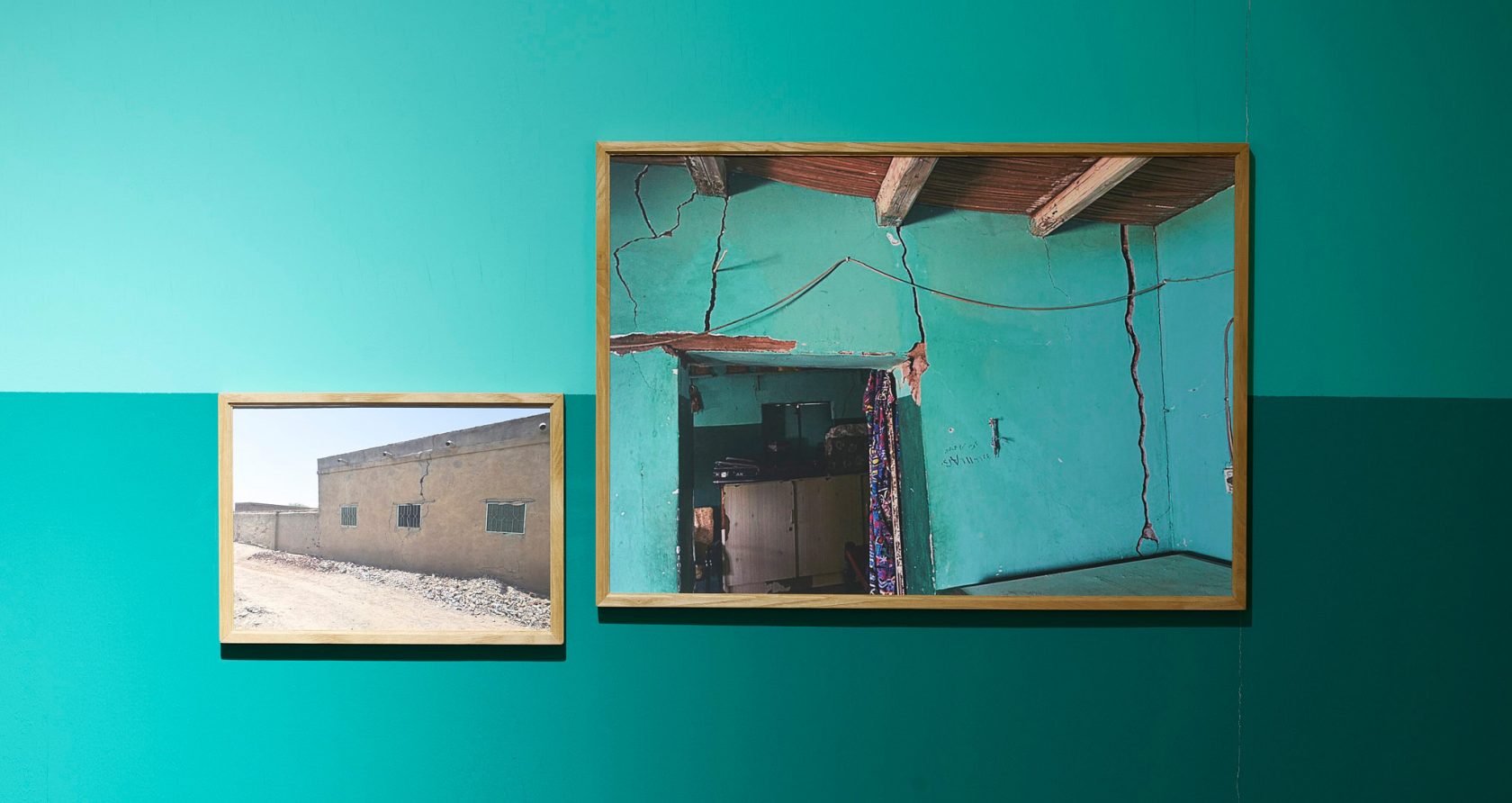

Translating the ‘spatial statement’ into program requirements, we were challenged to question and subvert its systems of exhibiting and material supply and analyze its impact on spatial needs. Aside from the ridiculous pacing of shows in exhibiting institutions and the wastefulness that is coupled with them, Buro Stedelijk would need to be able to sustain itself and its collaborators with the amount of material support currently received. As designers, we wanted to turn scarcity into an abundance of possibility to help an arts institution mirror the richness of art and life itself. It meant rethinking the possible extent of collaboration, participation, and access on multiple levels. What if visitors and collaborators would contribute to the space by leaving something behind and thus introducing a (perhaps rudimentary) aspect of mutual aid into the processes of a cultural space? What would Buro Stedelijk look like if it were a space for continuous learning, building on a collective material library? How could Buro Stedelijk offer spatial support structures for the new influx of ideas, manifestations, and interventions? And would these interventions be considered additions to the design – to what extent should architects anticipate what might happen within its creations, and be the ones to ‘permit it’? This sets us up for difficult entanglements, balancing requests from the curators with the practical needs of ‘use’, even if that means, counter-intuitively, producing messy processes.

Throughout the process, Jelmer and I did not want to remain the sole ‘designers’ of the space, even though a foundation of ‘support structures’ had to be laid for users to feel welcome to respond to. We aimed to offer designed layers that stood out but were adaptable to mood and practical needs; also necessary for the ‘identification’ of Buro Stedelijk. These layers had to be timed well, some could be realized at the immediate opening, while others would need time to manifest themselves. All in all, the intention was for the space to never be able to return to the white cube (that it, already, never was).

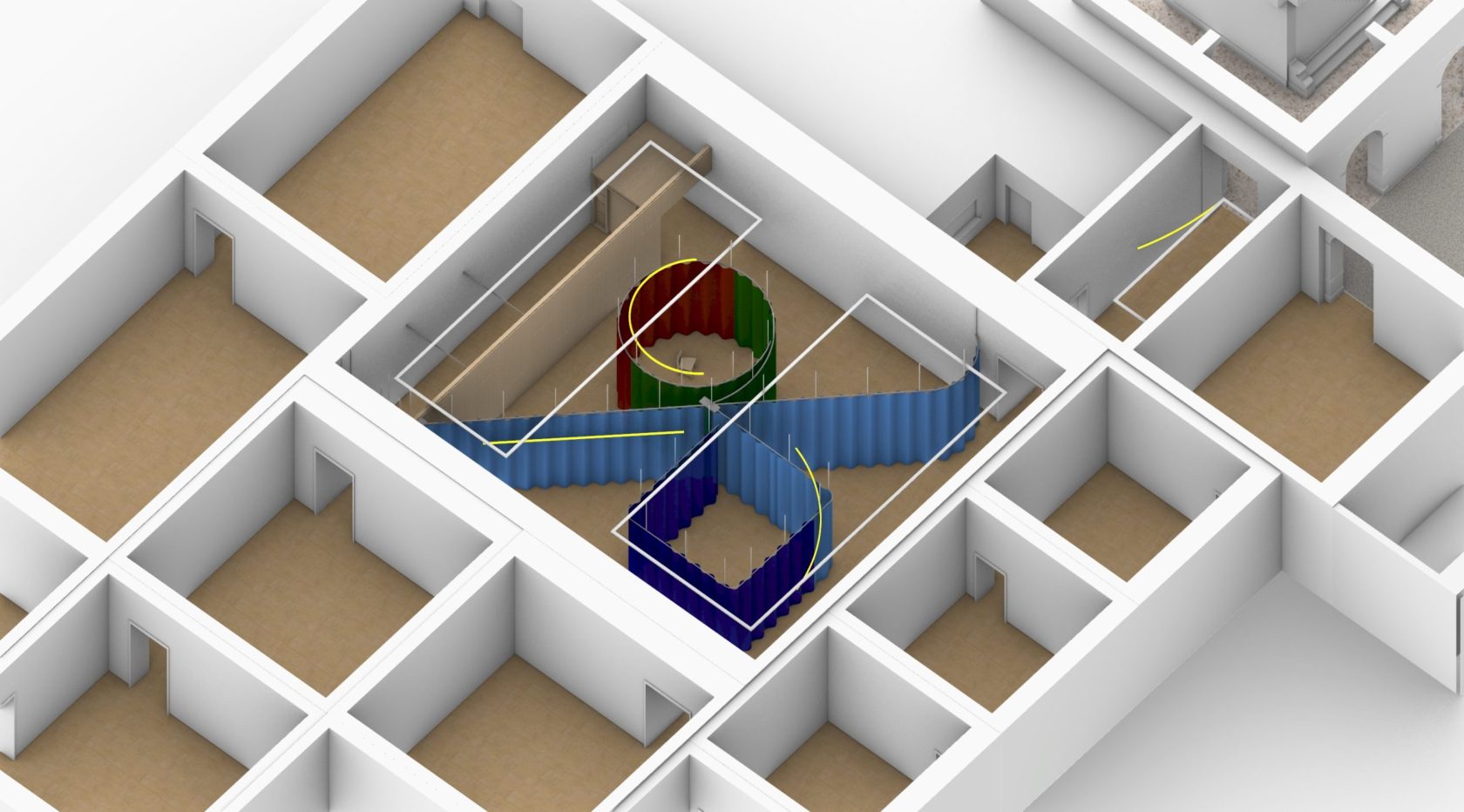

In the first sketching phases, which I took on, I projected the interventions to span from the entrance, via the Studio Space and Central Space, signaling a route to urge Buro to stand out against Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam. The precarious act of ‘interfacing’ with the institution was sought through the act of layering materials, exploring intersections of multiplied interventions – to be able to resound the many faces of Buro Stedelijk. In later sketches, I toned this down to primarily take effect in the Central Space and the short corridor leading up to it. The Central Space at that time was a darkened viewing room, with a corridor and unstable mezzanine to the left side of the entrance. The height was, as in other Stedelijk spaces, excellent for stacking vertical elements that support lines of sight.

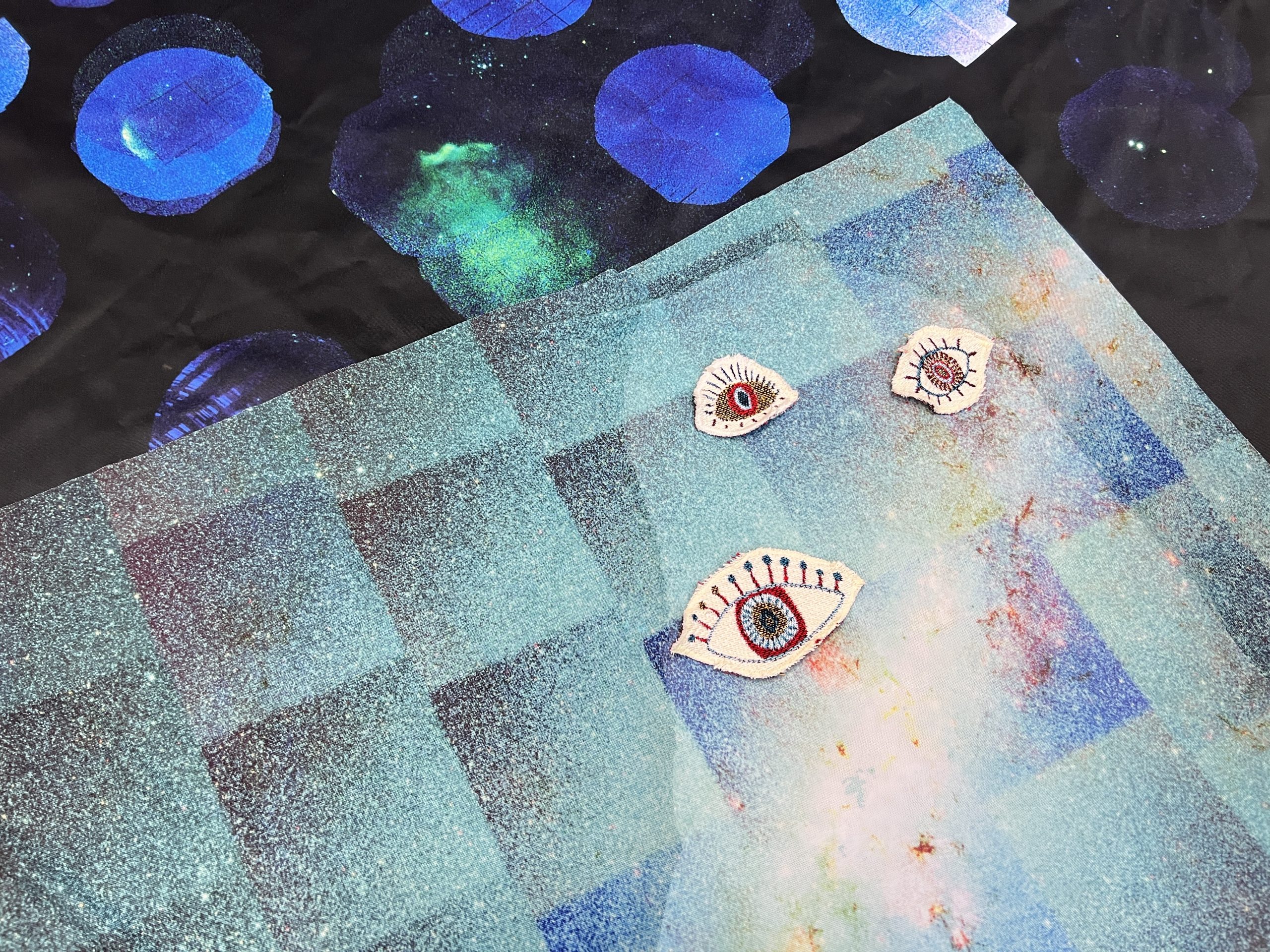

Since the material condition for the design was austere, the aim was to have the design carry as much impact and contrast as possible. Here we again committed to the Buro as a holding space, anticipating (un)known ways of use. In this early phase, three elements became clear: the scripts (of usage), to negotiate additional layers of intervention; the storage, to hold supporting elements like furniture, tools, and left-over materials; and the use of curtains (reused from our earlier Sonsbeek x Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam exhibition Abstracting Parables), to manifest a range of rehearsed and endless unrehearsed spaces.

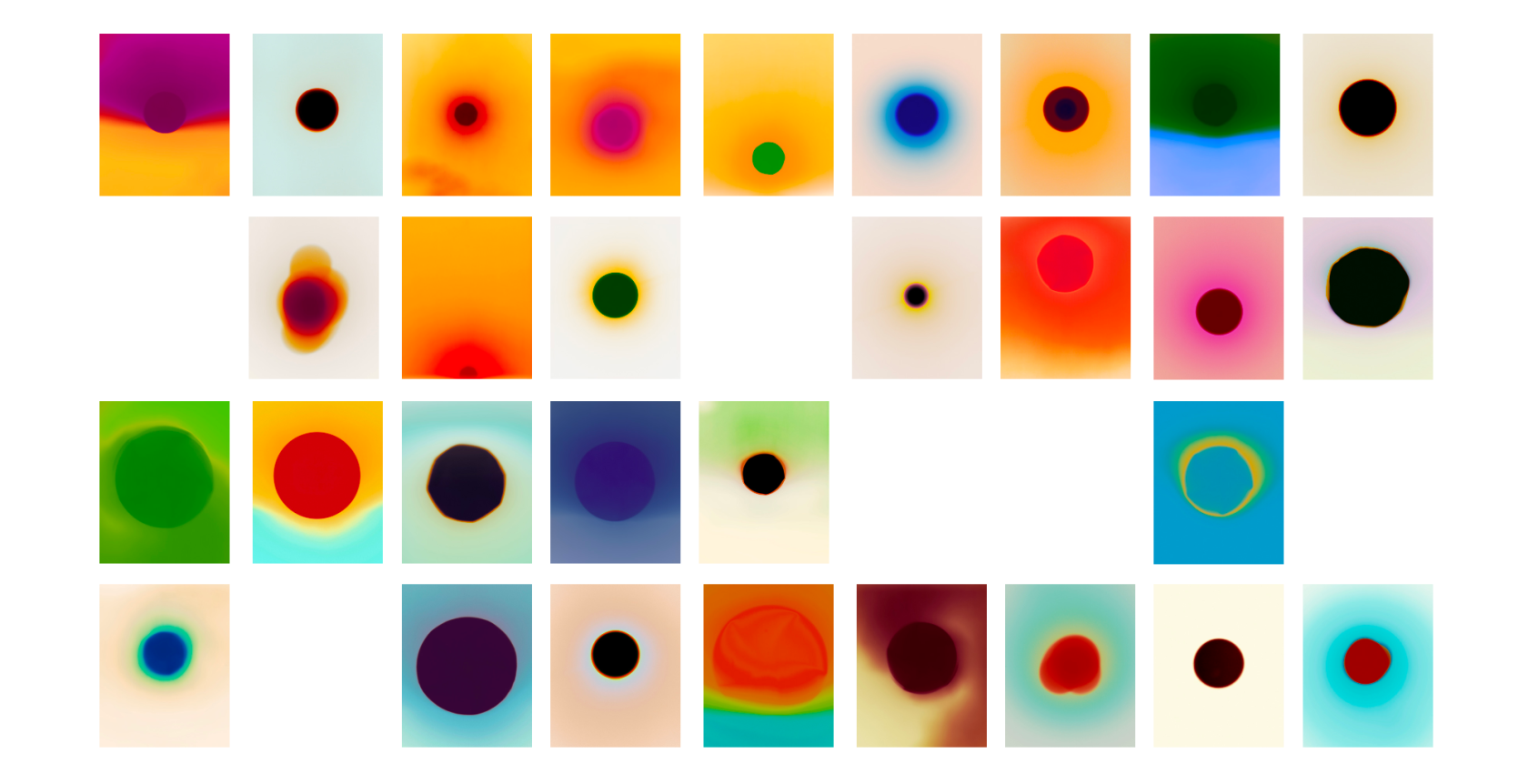

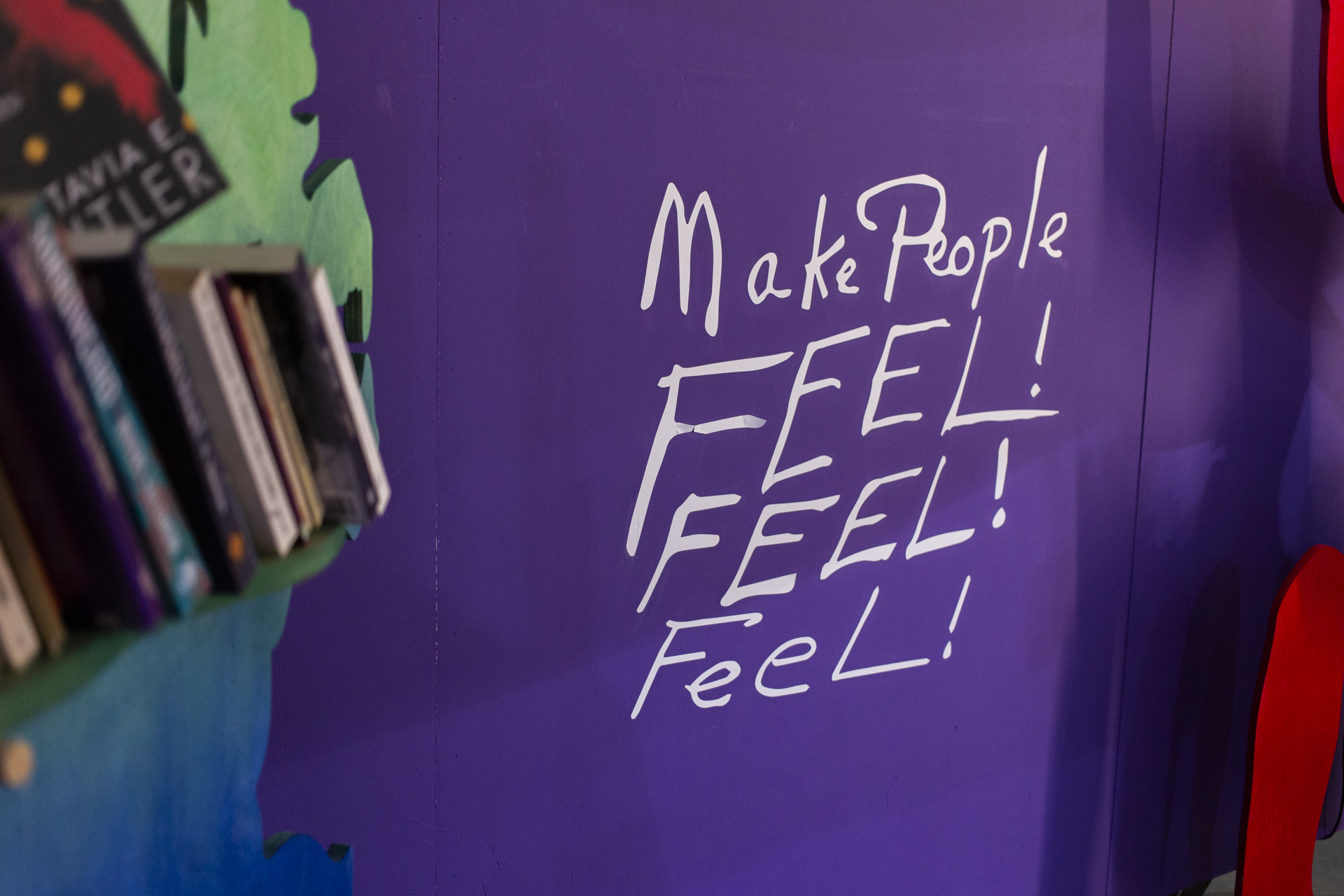

These elements formed the foundation from where to play and start exploring ways of expanding the program and (un)intended gathering through the ways the curtains, the wall, and (later) furniture could behave. What are the various ways to hang out? How do bodies typically move, and how would they be nudged to move differently in an arts space? The curtains and storage space are lines and forms that affect bodies, as well as respond to each other—to make smaller and larger gathering spaces for different settings as well as colorful backdrops to artworks; doubly testing the white cube. Introducing a heavy-duty curtain system makes changes to the set-up possible, which can facilitate improvisatory gatherings. As a following ‘material’ layer, we designed the lighting system to converse with the (counter)forms of the curtains, curtain system, and storage space – accenting important nodes. The colored LED neon-like tubes again have the capacity to adapt to the moods and needs of its users, making an immersive space; almost as if no fixity of color is needed anymore, a richness can be expressed between the art, the light, the curtains, and the wall—a machine for manifestations. We hoped to have made a canvas to dream the institution differently. Important was and still is how the caretakers of the spaces allow new scripts for such collective processes to happen and remain.

In the construction phase, as with any design, the trust between the architect/designer and builder is key for good execution. We detailed the elements so that they could be made with standard materials and in standard sizes, as well as reusing as much material in situ as possible. Here so much more was aspired: collective building and even more careful sourcing of material. Unfortunately, the aspiration was met with a pressing urge to finish the work and open Buro Stedelijk. Again, Jelmer and I considered the biggest task at hand the ‘aftercare’: successfully making use of, innovating and surprising, leaving behind, sharing, and feeling comfortable enough to just hang out. The design would have to be supplemented, and the usage over time would clarify which ‘tuning’ elements, like furniture, were needed, and who would make these. The Buro Stedelijk curators, project leader, and team have a responsibility to encourage such usages and suggest alternatives to the creeping, knee-jerk response of the white cube.

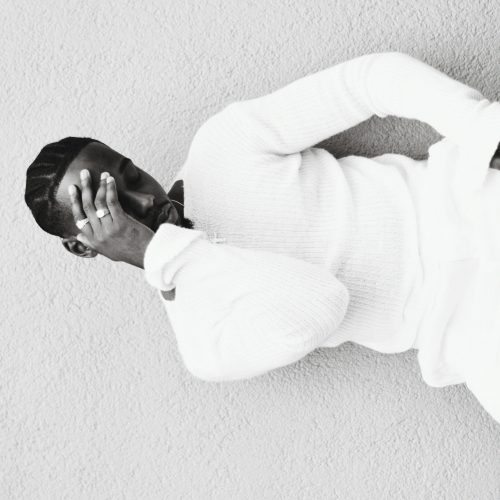

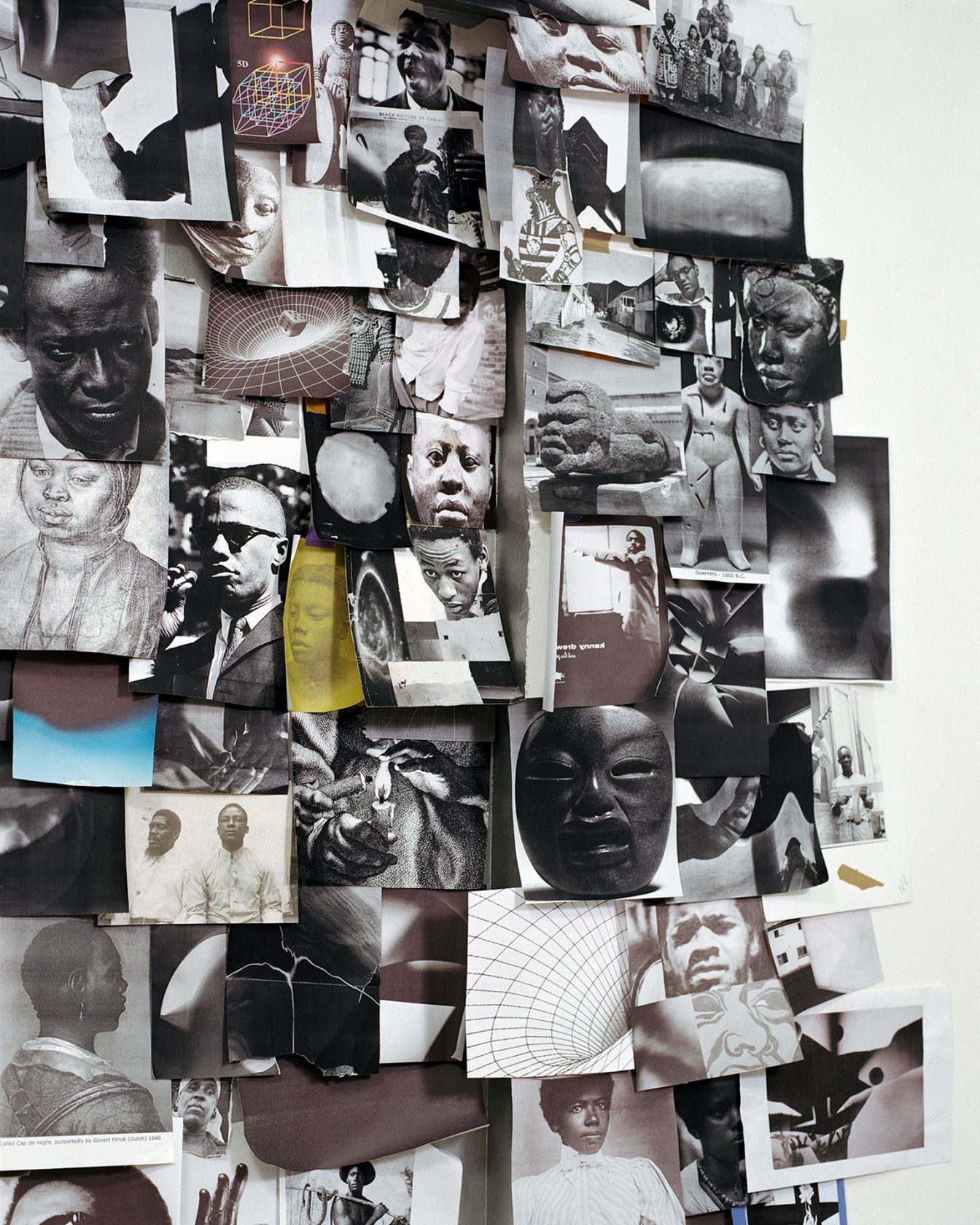

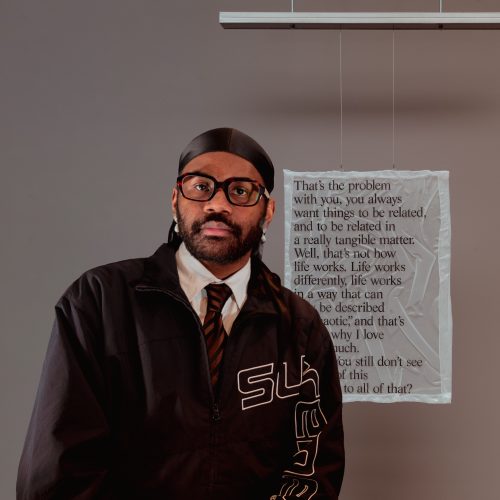

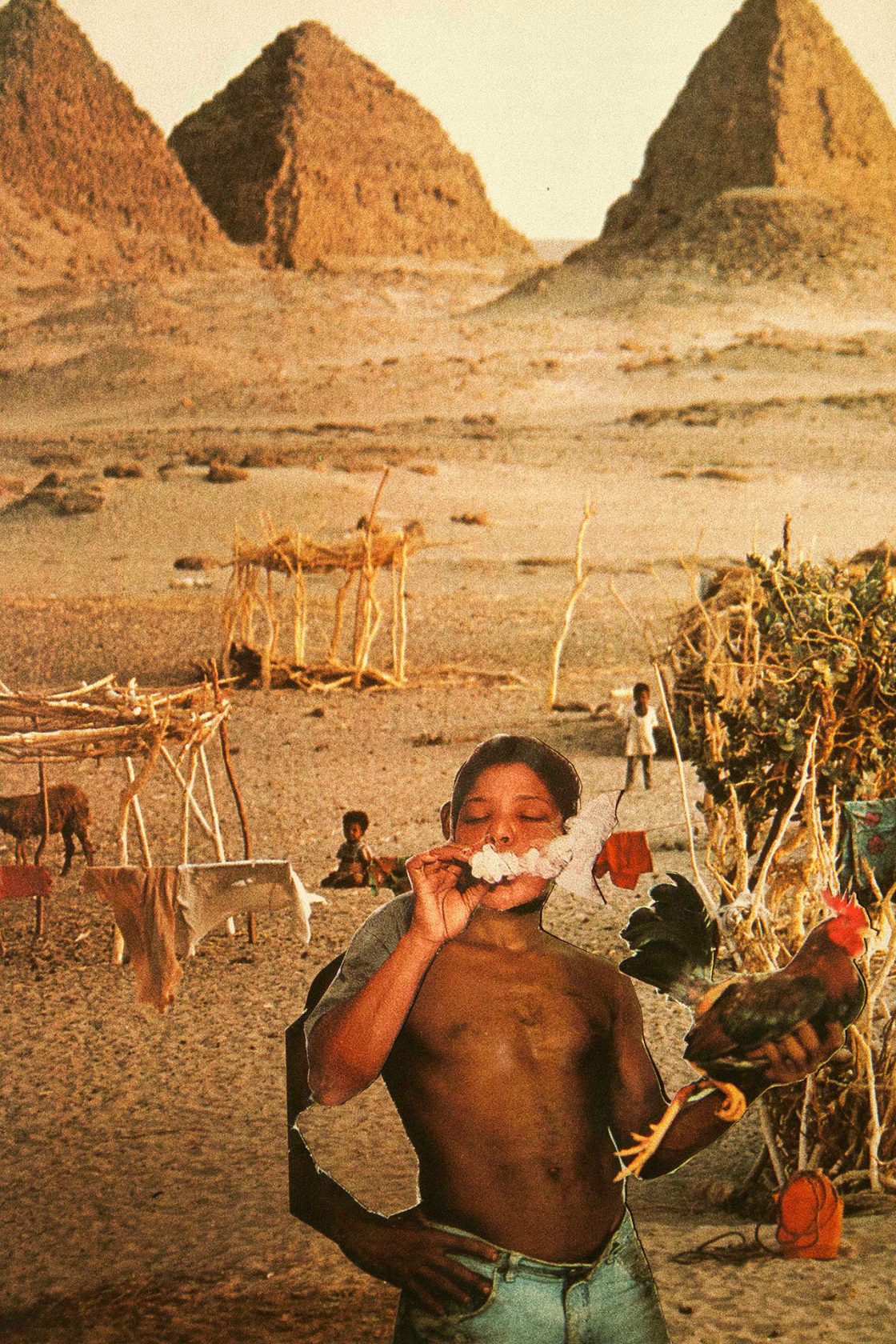

One of the most inspiring interventions in the space was the Raw Heat, Black Sweat gathering co-curated by Marcel van den Berg. The space became a block party, with many actors—the atmosphere was convivial, messy, loud, and urgent. The storage wall was used for the DJ Booth. The artwork on the walls, the curtains, and the lights enhanced the movements of the gathering.

When trying to capture both the aspiration and the attainable, this design vision for Buro Stedelijk still has many concerted trials to undergo. In the remaining years of Buro Stedelijk, how can it intuit, interpret, and reflect the cultural spaces Amsterdam needs?

¹Avery F. Gordon, citing Ernst Bloch, throughout The Hawthorn Archive: Letters from the Utopian Margins, 2017