From Listening to Reflecting: Thoughts on ‘Manifestation #1: Listening Sessions’

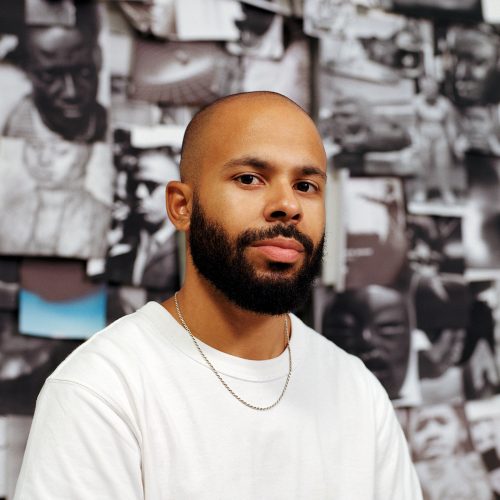

by Naema Abdi Ali & Anna-Rosa van Wees.

In my vision, the arts have the potential to bring people together in new ways by placing social relationships, aspects of daily life, ‘care’ and life stories in new contexts. This means that the arts not only create a (critical) space to reflect & to innovate, but also create space to celebrate and support life stories and social relationships. My interests as a researcher and curator focus on long-term change; globally & locally. I approach such themes through (micro) histories of resistance, by analysing power structures; always in connection to the present and the future; embodied in the arts. I am inspired by my educational background in museology, post/decolonial studies, migration, climate justice, ritual studies, cultural analysis and feminist studies. From this place I wrote my reflection on the Listening Sessions.

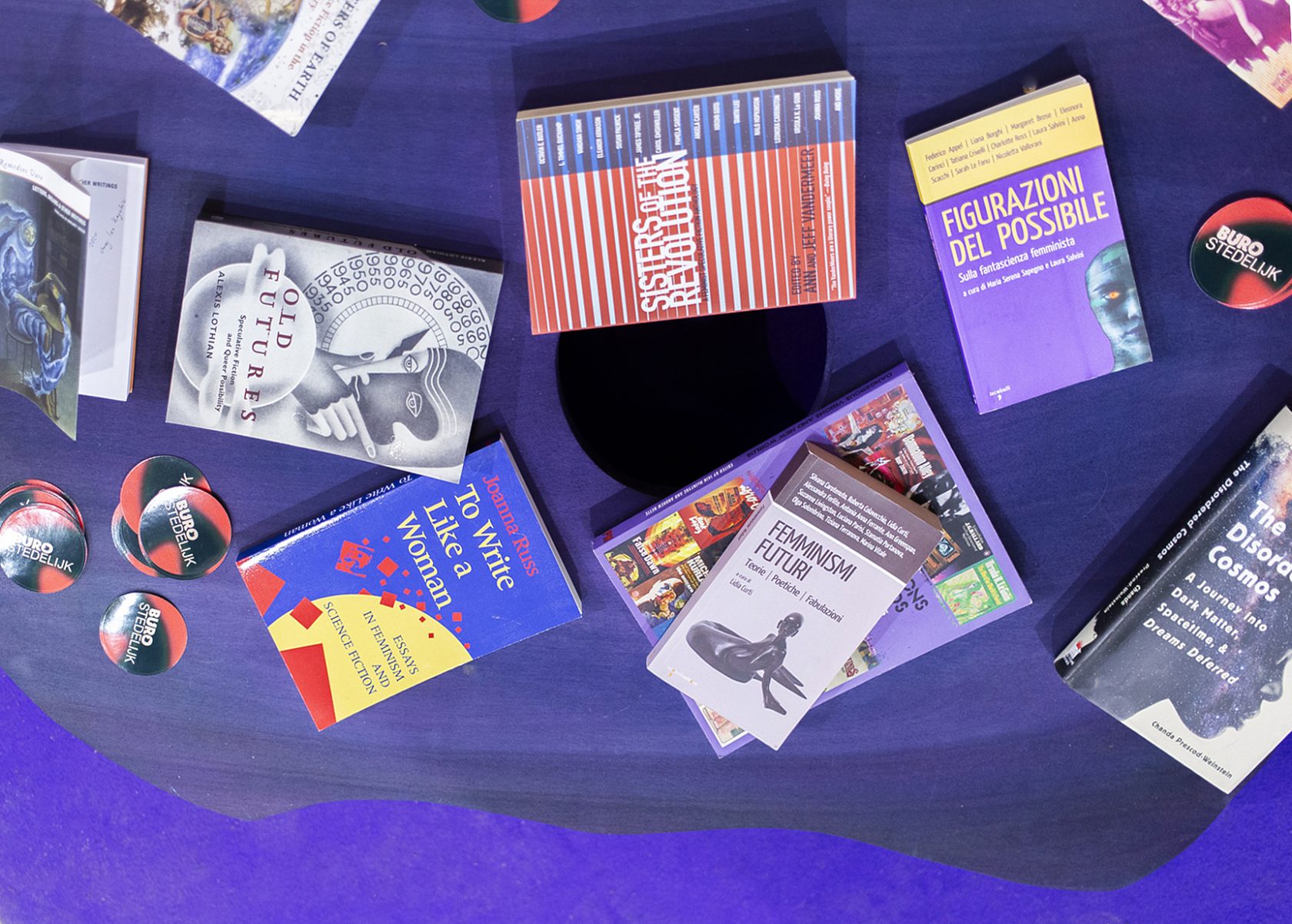

Listening for two days was a fun exercise; seeing the many layers in which the arts have the potential to facilitate different ways of presenting, delivering labour, curating and story-telling was very inspiring. Much gratitude to the team of Buro Stedelijk.

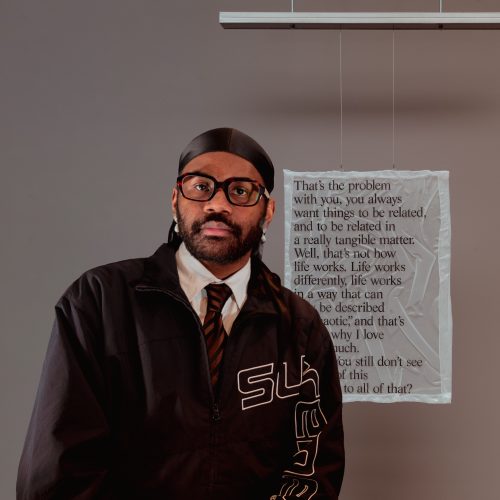

The arts hold the power to help us see the world differently. A longstanding intuition of mine has been that art is not an agentless material ‘thing’ but rather a ‘doing.’ My goal as a researcher is to re-imagine new ways of being and doing through artistic, curatorial, and institutional interventions, bridging theory and praxis. I believe that new and radical perspectives are never born in isolation, but are rather the complex entanglements of different histories and knowledge. For this reason, I always strive to use an interdisciplinary approach within my work, while recognizing the situatedness of my own knowledge. My overall practice is informed by my educational background in museology and cultural analysis, as well as my own experiences as a Malaysian-Dutch woman navigating the arts and cultural sector in the Netherlands. In my reflections on Buro Stedelijk and the Listening Sessions, I draw upon my interests in queer-feminist, post/de-colonial, phenomenological, affect, and environmental/ecological justice studies.

In the same way we – and many others – envision Buro Stedelijk as an ecology, this reflective essay-of-sorts operates as one too. Together, we have attempted to map out a constellation of different ideas and practices that we have absorbed from the Listening Sessions and believe should guide the future of the institution. While it was not possible to reflect on every presentation or idea put forth in the Listening Sessions, we are grateful to have been in the presence of many inspiring thinkers, artists, and performers in the span of two days. In producing this text, we, therefore, hope to have laid out a conceptual toolkit for institution-building; for envisioning new relations at Buro Stedelijk and beyond.

Over a span of two consecutive days, Buro Stedelijk proffered a space in which participants from all walks of life could come together – physically or virtually – with a sole purpose: to listen. In a society where voice lies at the forefront of politics and activism, Buro Stedelijk shifts our attention to the importance of being fully present and listening to the other. It was thus decided beforehand that everything would exist at the moment. This ultimately meant that no recordings of the sessions were made and no presentations would be uploaded online. As writers that have been asked to document the Listening Sessions, this idea felt initially challenging. There is an innate pressure to have our pens ready for exhaustive note-taking and critical questioning. The problem that this seems to create, however, is that we leave ourselves with little time or space for authentic connection. And so, Naema and I gave ourselves permission to do exactly what Buro Stedelijk wanted us to do. Listen. Take home what resonated. Our experience of these sessions was not always the same. While I may not have remembered every presentation, it was this very concept of resonance that brought this text to life.

I first heard of the notion of resonance from Stephanie Schuitemaker and Berber Meindertsma as they spoke to us about the importance of hosting within art spaces. Resonance, in their words, is a moment in which one feels a vibrant connection with the other. Such moments are rare, unforced, and vital for transformation. We might begin by returning to a moment in which you walked into an art space and were truly moved. Many of us may consider the term ‘moved’ solely within the framework of emotions; a profound emotional response that follows an encounter. These moments, however, are temporary and individual, and our values or knowledge systems tend to remain unchanged. As I search for a particular memory, I realize such an experience did not occur to me until the Listening Sessions. While I cannot speak for everyone who was there, I believe I carry a better understanding of what it means to be moved — that is, how art (spaces) and encounters can compel our bodies to take meaningful action or impact the orientation of bodies in new ways (an idea which I pull from Sara Ahmed in Queer Phenomenology). These moments, by contrast, produce lasting effects that transcend the spatiotemporal framework of the event or exhibition itself.

In search of a way to expand upon my reflections, I want to consider the Listening Sessions through a broader framework of resonance. In physics, resonance denotes the phenomenon in which an oscillating object causes another in close proximity to do the same, resulting in a sound. While I am by no means a physicist nor am I particularly concerned with exploring their physical properties here, it is this peculiar relationship that speaks to me the very essence of listening. As we come into proximity with others in the act of listening, a chain reaction is produced, giving force for new meanings, ideas, and affects to emerge. It is precisely this rippling effect that informs my interest in writing about resonance here. As I continue to gather a more concrete understanding, questions emerge. What does it mean for Buro Stedelijk to become what we might call a ‘resonant space’? What are ways of ‘making’ and ‘doing’ that may facilitate resonance, bridging the gap between theory and praxis? As a way of tying some of these knots together, I reflect on the Listening Sessions through my encounter with the spatial layout and design.

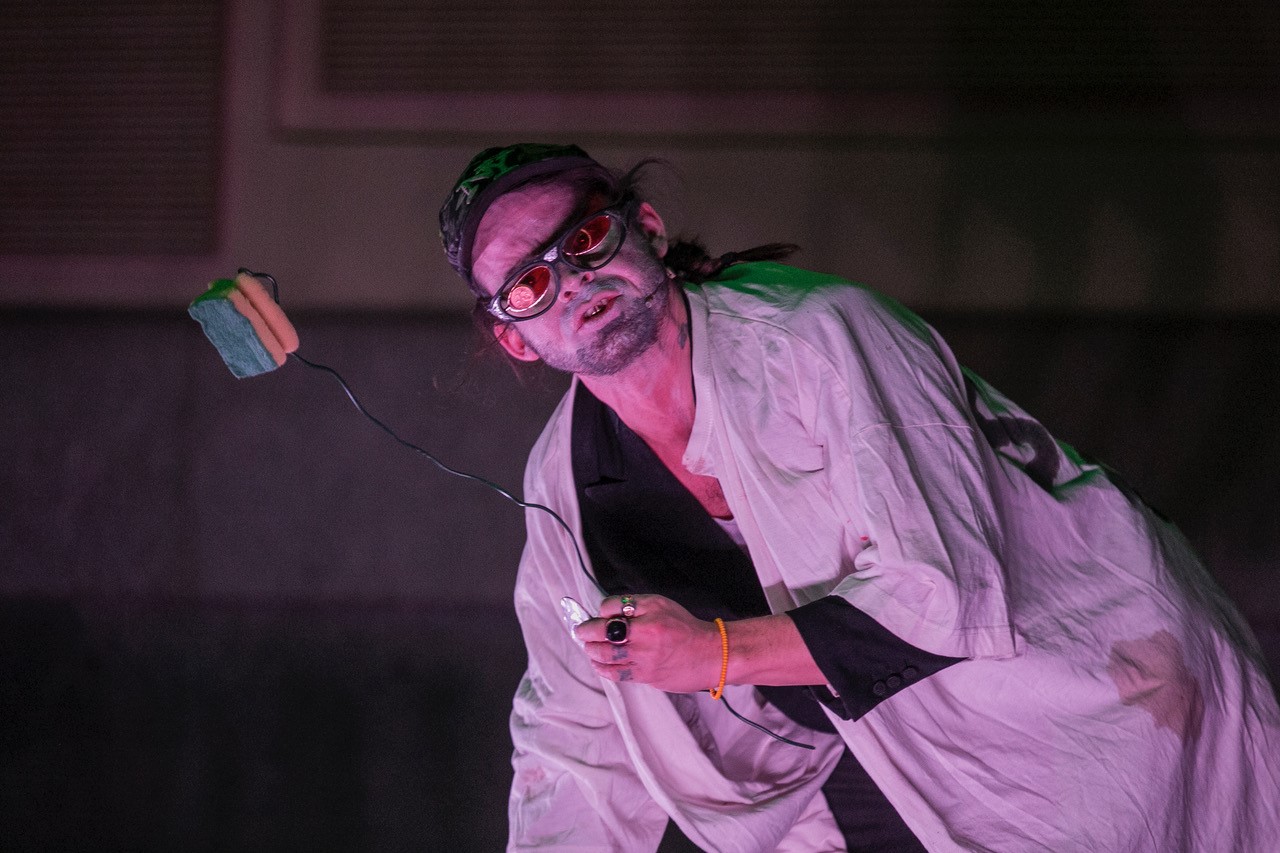

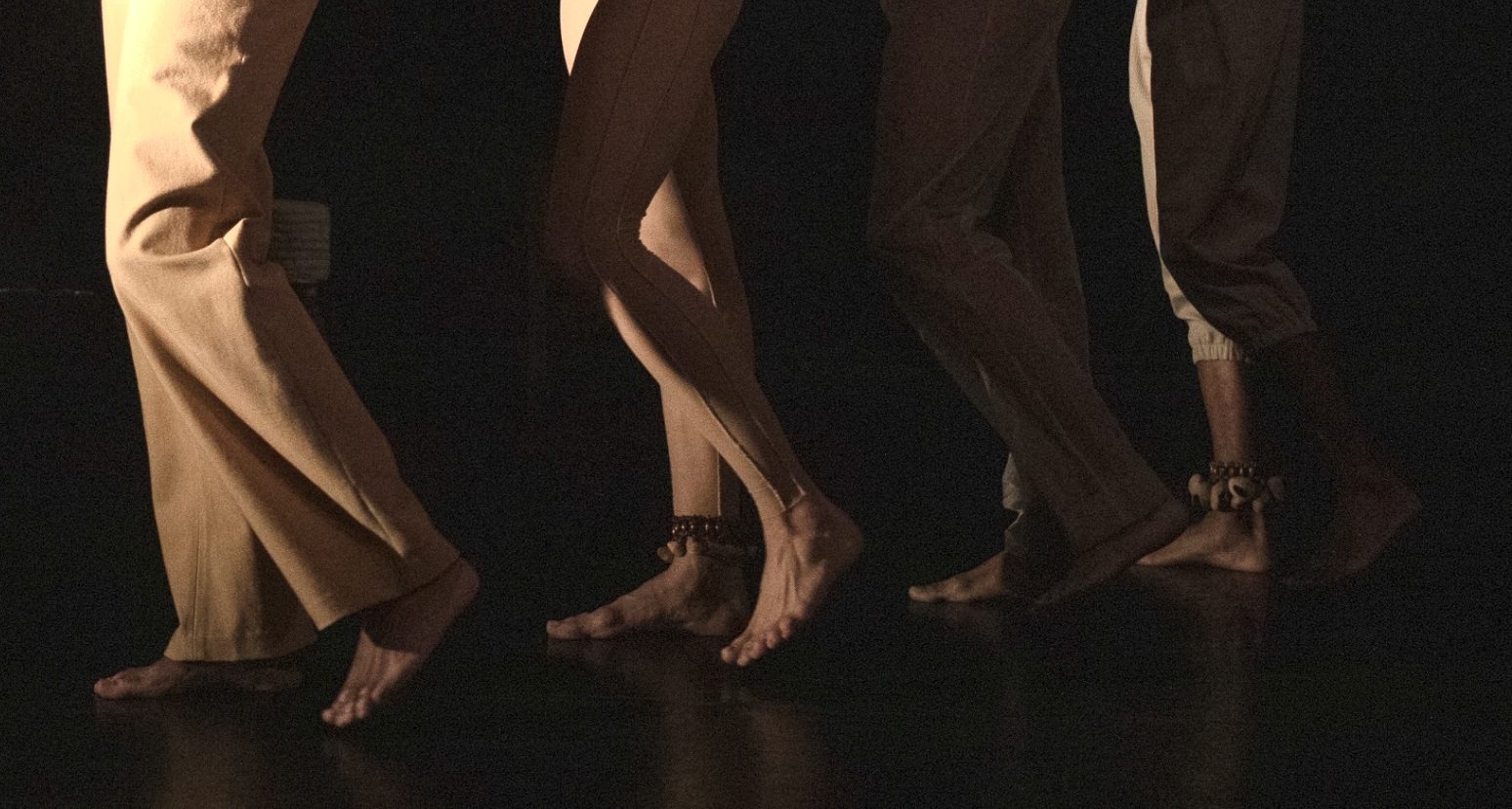

One of the main features that stood out to me about the Listening Sessions, and perhaps most overlooked, was the malleable seating arrangement. With a background in Architecture Design from the Gerrit Rietveld Academy, Frédérique Albert-Bordenave enacts an experimental space through which new relations are constructed. As such, the artist’s work invites us to reflect on the role spatial design might play in mediating a resonant space. The arrangement began as more akin to a traditional classroom or lecture hall, wherein each individual sat forward-facing on rows of long benches. As the days unfolded, these arrangements continued to evolve into miscellaneous forms — diagonal lines; a square format; and occasionally, in reverse. With these changes, speakers could also choose how they wanted to present. Whether it was sitting amongst the audience, standing in the middle, or presenting at the back, the possibilities for re-configuration were endless.

Writing about a seemingly modest seating arrangement is no random choice, but rather an entry point for thinking about the mediation that occurs across various scales. While there were moments to laugh about which way the audience needed to face, it was clear that this fluidity brought a sense of vulnerability and connection. As the distances between host, speaker, and audience began to collapse, a collective gaze was formed — something which I believe is lost within a traditional museum conference or symposium layout. My point here is to remind us of the impacts and relations that might be created through smaller practices, particularly as they become entangled with broader movements of social and ecological justice. Envisioning the spaces we occupy as interconnected ecologies is what Stephanie and Berber seem to get at in their re-invention of traditional hosting practices in art spaces. If resonance requires space, then museums and cultural institutions seeking to mobilize change through discursive platforms must recognize what alliances are being formed in the very spaces they are held. In this respect, I am eager to see how Buro Stedelijk explores the intersection between space and resonance within its design practice.

Positioning Buro Stedelijk as a resonating space demands that we re-think museums and cultural institutions as sites of affective embodiment. Moving beyond the longstanding belief that they are first and foremost spaces of education, we must contemplate ways to engender room for connection; healing; transformation. It is, in the ideas of Stephanie and Berber, about creating a ‘living ecosystem’ constituted of various agents. Thinking about resonance as more than phenomena but also as relationship, space, discourse, and praxis, can provide us with an alternative way of thinking about momentum and change. It may start with the mere act of listening, but it is even more importantly the creation of an ecology between human, non-human, and more-than-human worlds.

An artistic space that aims to experiment has to know the reality in which it operates. It has to be aware how it tries to differentiate and in which ways it will not (yet). Listening to reflections on the art scene in Amsterdam was an interesting and experimental step in the right direction. What remained vague was what happens after listening. This caused the sessions to feel like a void in which information resonated against the wall; without a clear intention as to what the goal of listening was; seemingly happening in a neutral and open space. This void evoked momentum for deep listening, something which I applaud. But, it remains vital to return to reality; to then attach concrete actions to what has been understood. Hoping people are actually moved to change personal and collective habits & values.

Positionality is defined as the social and political context that creates identity in terms of race, class, gender, sexuality, and ability status. Positionality also describes how identity influences, and potentially biases, the understanding of and outlook on the world.

Although positionality is fundamental in understanding the world, it does not stop there. The decisions made after understanding positionality are crucial. And then the work still continues as the world is always changing, and so will the positionality of a person, space or object. Looking at the intersections of art(ists), academic(s) (institutes) and cultural institutes, many more factors influence the positionality of these spaces. Some of these intersecting factors were a recurring theme during the Listening Sessions, serving as a warning of observed phenomena in the arts.

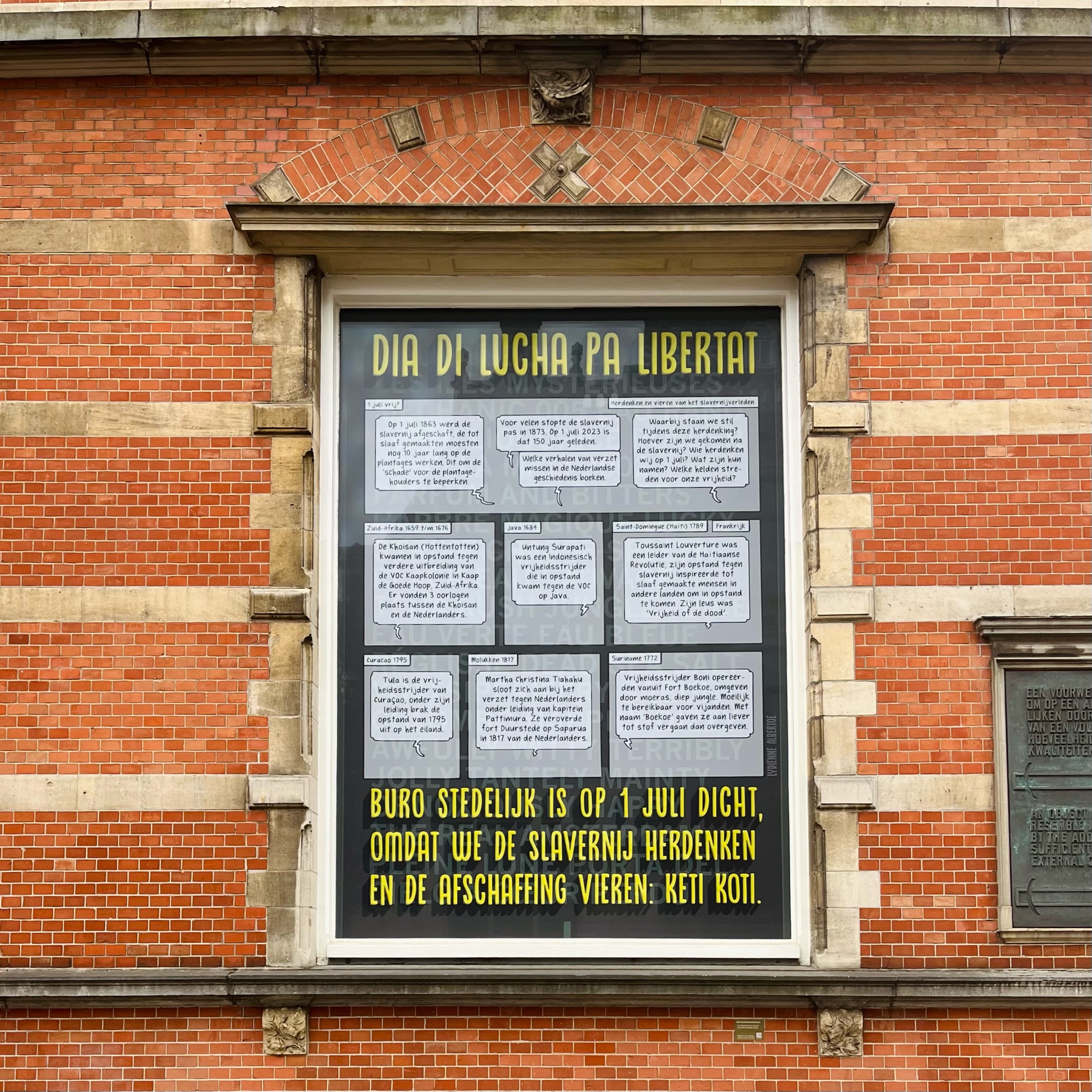

Buro Stedelijk – Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

The listening sessions started with a look back on the previous version of Buro Stedelijk: Stedelijk Museum Buro Amsterdam (SMBA). In an article in the NRC, Rein Wolfs (Artistic Director of Stedelijk Museum) explained his vision for Buro Stedelijk:

“The idea behind it is that the ideas that young creatives in the Netherlands can easily

be fed back to the museum. That is also why the successor to [SMBA] is located in the

museum itself, […].”

Although I am personally excited for an experimental artistic space, one of the biggest disappointments was the fact that it will be located within the museum. Being situated within the museum means that the Buro Stedelijk will have to experiment and make meaning within the walls, policies and rules of a larger institute. No doubt will this pose difficulties for the Buro.

Manifestations #1: The Listening Sessions

During the Listening Sessions I sensed the urgency for a place that truly diverts from normalised (institutional) practices; be that a diversion from academia, cultural institutions, art schools and even (established) galleries. The longing for a breath of fresh air was omni-present. I hope the Buro will intervene in the local discourse together with the communities & professionals residing in Amsterdam. That the Buro may be a generative space in which artists & ideas are born through facilitating new connections between people in & outside the art scene.

I usually enter my reflective space after talking to people. Anna-Rosa and I met up over coffee with Basir Mahmood (a collaborator of Buro Stedelijk) as all of us were producing something in relation to the Listening Sessions. In this conversation we concluded that solutions to systemic issues within and outside the arts sector must have a stronger impact than the problem has had, for it to come close to repairing damage. Based on what I heard during the sessions, this translates to the hope for better labour conditions, a climate friendly arts sector, a re-scripted art space that is not the white cube, ethical funding and an art scene that re- imagines realities and generates solutions & possibilities.

But, repair reinforces existing structures, that is not the goal. During and after repair there is space to create new structures. One way the Buro could contribute in the pursuit of realising repair & that which lies beyond, is by facilitating the creation of ideas that will outlast this experimental space, so that when the money stops flowing, the impact remains and can be built upon in the future.

We live in a complex world with many stakeholders, a grey area that seems endless and many intersecting complex power structures. The reality of this knowledge and assessment of your individual position in this world can lead to exhaustion, to analysis-paralysis. Engaging on this level of complexity thinking requires constant self-evaluation accompanied with emotions like ambivalence, grief, anger and despair.

It has become clear, however, that in the coming decade(s) radical change has to happen; several crises are intersecting and apocalyptic scenarios become more real everyday. But there is a collective concrete utopia people are working towards, embodied by intersectional climate justice. Ernst Bloch (1885–1977) coined the term concrete utopia and distinguished the term ‘concrete utopia’ from ‘abstract utopia’. In Misha Kakabadze’s blog they write that “the distinction signifies that which is actually possible and realisable vis-à- vis an emancipatory ideal. A concrete utopia is a concept that signifies potentiality, but one grounded in the real, existing socio-economic and political conditions of a given context. The indicator for what is possible or realisable in a concrete utopia is not whether something is realisable in theory, but in actuality.” They continue using the example of the Paris agreement in 2015: “it may be possible in theory to achieve the climate goals of the Paris Agreement of 2015 peacefully, but reality presents a wholly different picture.”

Returning to realistic change is humbling and expansive at the same time. The ‘long breath’, as we say in Dutch, is used commonly as metaphor for the slow resonating power it takes to achieve large-scale, long-term change. The reality of existing within that long breath is what I am trying to grapple in this reflection.

This concrete utopia (intersectional climate justice) has to be manifested materially and metaphysically. Penashe Chigumadzi beautifully worded the synchronicities and urgency between these modes of ontological thinking in her Nelson Mandela Lecture 2023:

“Transatlantic Slavery is the material and metaphysical womb of the modern world our enslavers and colonisers know. […] What is capitalism if not a system for sorting who is most fit for exploitation and extraction? […] We must think the unthinkable, and demand the impossible of this world. […] The gift of our own historical memory and consciousness is a freedom from a teleology that dictates that this is the only World is possible or even desirable. It gives us understanding that the world that we have is not inevitable or permanent, it is historically contingent and constructed. Armed with ancestral memory it is up to us to participate in history and to end this world. We know that reparations of transatlantic slavery and colonisation will bankrupt the west and collapse its economy. To this we say: let go of your ill-gotten property. We must love ourselves, our ancestors and our unborn enough to end this world.”

The arts can:

- embody the message that this World is not inevitable or permanent

- facilitate concrete & fantastical imaginations of the cultural shift needed to end the world as we know it

- imagine the unthinkable and pose the questions that ask for the impossible

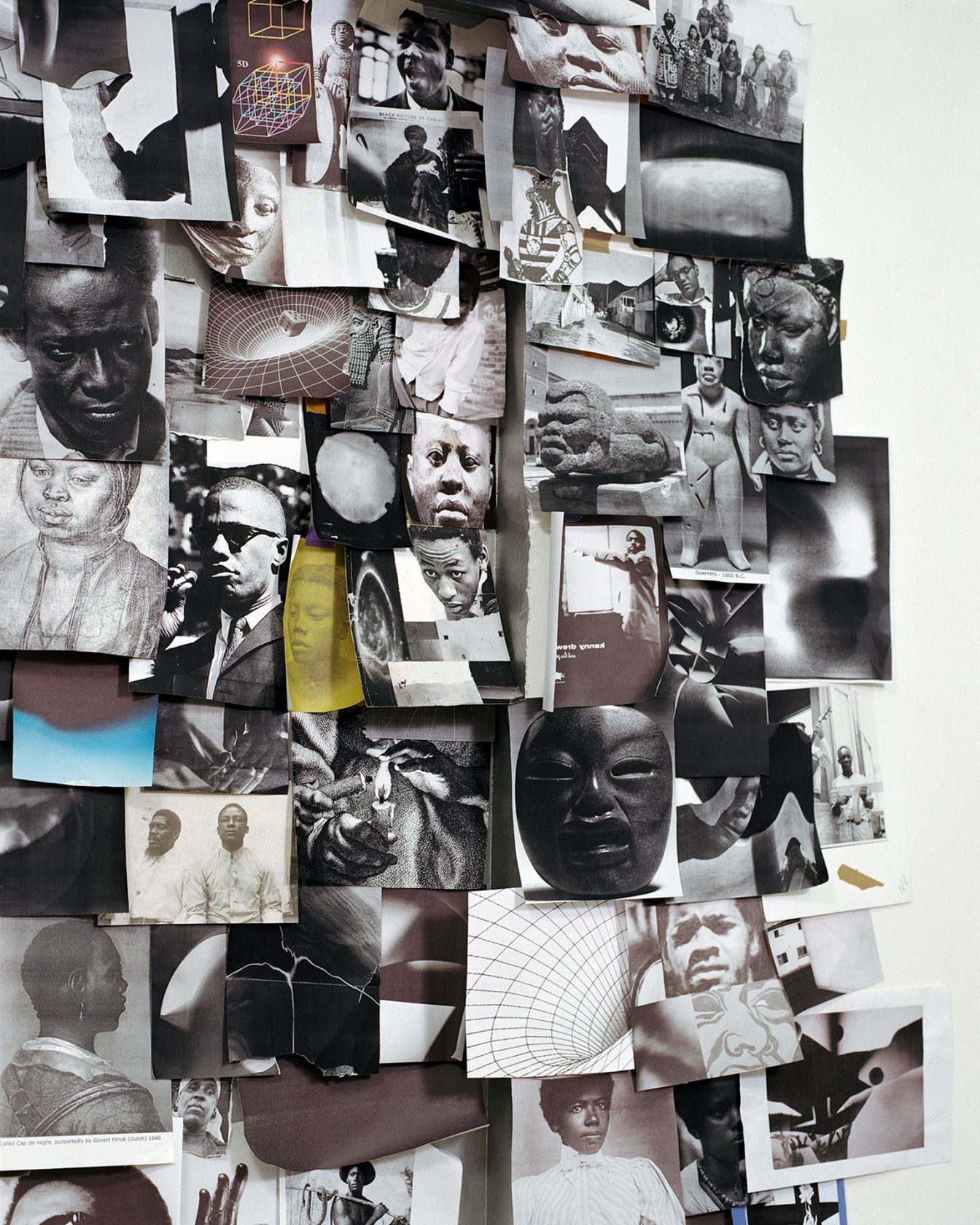

Each of the collaborators added something speaking to specific histories, ontologies, cultures, ecologies and communities. Working from this framework allows for listening and care to take central place in art(-making & -education), facilitating opportunities for understanding, conversation and concrete action. Art can appeal to our mind in many varying sensory ways, unique to each person. Approaching learning, conversation and understanding in this way can inform cultural and political discourse, creating potential to arrive at a more accessible and participatory paradigm.

What initially drew me to Buro Stedelijk was its claim to serve as an “experimental observatory” for exploring new ways of being and doing. As a researcher in Museum Studies, I see this move as part of the larger New Museological paradigm where museums and cultural institutions deliberately attempt to break away from hegemonic narratives and norms. Despite being a complex and multi-layered concept, ‘experimental’ seems to have become yet another commodified buzzword in the arts and cultural scene. As Viviane Tabach explores in her ongoing research “Moving Basis: Art Mediation as Institutional Critique,” the seemingly inevitable risk of fostering artistic experiences (in this case, an ‘experimental’ one) is that they become institutionalized and commercialized insofar as the public turns into consumers. How, then, should Buro Stedelijk imagine itself with regard to these frictions and fragilities?

Let us begin with failure.

I believe what sets a true experimental space apart from others is its ability to embrace failure. My understanding of failure as a productive framework stems from my own previous engagements with queer theory in museological practice, most notably from the works of J. J. Halberstam. To be clear, failure here is not the refusal of moral or ethical responsibilities. Rather, failure is about rejecting the hegemonic frameworks that define ‘success.’ Simone Zeefuik’s presentation shows us how rest is a form of resistance to the capitalist logic of success: hard work; financial wealth; linear progress – to name just a few. She primarily situates her discussion from the perspective of Black creatives and cultural producers, who often feel the only way to be merited in the art world is by abandoning their own desires in exchange for more work opportunities. Instead, she allows us to see the importance of disrupting this linearity in order to open up new possibilities for unexpected pleasures and self-expression. I find that Simone offers a refreshing perspective on what embracing ‘failure’ can bring to artists and creatives alike, and I am greatly inspired by her words to take more rest in my own practice.

Another example I found myself reflecting on is the upcoming design of Buro Stedelijk by Setareh Noorani. As an architect and researcher at Het Nieuwe Instituut, Setareh’s practice draws upon queer, feminist, and post-colonial theories in what she refers to as the ‘de- scripting’ (or perhaps ‘re-scripting’) of institutions built upon dominant and oppressive systems of power/knowledge. As spectacles of power, museums have traditionally served as places to enforce fixed ideologies and govern bodies, oftentimes in more subtle forms that are overlooked.

This varies from the way visitors move via prescribed routes to the social codes of dressing and behaving. By adopting a fluid and playful DIY approach to the spatial design of Buro Stedelijk, Setareh crafts an experimental playground-of-sorts that simultaneously attends to the personal needs and desires of individuals who feel institutionally excluded. There are opportunities to sit, hide, reflect, rest, or (dis)connect – each encounter is rendered unique whilst being part of a larger ecology of experiences. I see Setareh’s practice as not only a way of de-scripting the rigid ‘white cube’ format adopted by several art spaces, but as one of many possibilities of how we might engage with failure in and as praxis. More specifically, I consider her integration of craft into the design – a traditionally relegated art form that reverberates with the everyday, the banal, the minor, and the ephemeral – as a productive form of failure that works to subvert the hierarchies of taste. Looking at the Buro’s inseparable relation with the Stedelijk Museum itself, however, I am curious and slightly skeptical as to how these contrasts will play out in practice. While these frictions ignite difficult challenges and conversations for Buro Stedelijk, I believe it is within this experimental space of possibilities that they are well suited to be held.

As a way of closing my reflections on the subject, I want to cite and adapt an excerpt from my own research “Queer Matter(s): Towards a Politics of Care in Contemporary Exhibition Practice” in the context of Buro Stedelijk:

“An orientation towards failure means to recognize and work within the constraints with which the [projects and exhibitions in Buro Stedelijk] are produced. This includes the impossibilities and hierarchies maintained by museums [and the Stedelijk a.k.a. the ‘Mothership’], the implications of geopolitical contexts, the ongoing colonial dynamics and heteronormative, capitalistic logics which shape knowledge production and subjectivity, as well as financial restraints. To embrace failure is to avoid viewing [Buro Stedelijk] as a completed product, but rather, as what Luther describes, a “fragile collection of struggles brought into being.” The transformative potential of failure, however contradictory it may seem, thus lies in its ability to illuminate the rigid hierarchies and power structures that ultimately govern or suppress production, audience reception, and inclusion in the context of art spaces.”

(2022, p.28)

To experiment is to fail and vice versa. However, failure must always be understood in relation to the very systems and structures that separate the good from the bad; the right from the wrong. My aim in writing about failure is to show that we can harness its power into a productive force, and we can turn to these instances here as starting points to learn. But perhaps most of all, failure will require us to temporarily dwell in the discomfort it may create. Only then can we pave the way for a new reality, towards a brighter and more hopeful future.